Several years ago, I gave a lecture entitled, “Why Do I Exist?” It appears in my book, The Universe We Think In. The “I” in the title means: “Why does Schall exist?” But it is intended to call anyone’s own particular existence to his immediate attention.

Looking at ourselves, we cannot deny that we are encased in this particular body, which has enclosed us since our conception. We all know the outside time limits of our personal existence in this world – the four score years and maybe ten. Very few of us, in fact, live that long.

Scientists, we hear, search for ways to extend the span of our years. But do we really want to live to be 150 years old? In general, on the average, we live longer than most generations before us. No doubt this lengthened longevity is a good thing, but it also adds different kinds of problems, both physical and spiritual, that did not much exist before.

When we look at ourselves, the “why?” question always comes up. We really cannot avoid it. Indeed, we do not want to avoid it. If every other thing that we do is done for some purpose or reason, we can hardly avoid wondering if we ourselves exist for a purpose that includes us and the life we lead in this world, whenever and wherever it is given to us.

The narrative we receive from revelation addresses this issue. The cosmos itself was created by God in order that He might associate other free and rational beings into the home of His eternal, triune life. In short, we were not simply created to be natural human beings, but to be human beings elevated to a status beyond the confines of our given nature. Our status as finite beings remains. We are subject to death. We are likewise destined to eternal life.

Recently, I was sent a genealogy of my father’s family. Records show that the first Schall in our line came to the States in about 1847 from Germany. As we all know, had such ancestors not existed, we, as we are in our genetic heritage, could not exist. On our bodily side, we are results of previous generations.

Had the world, or any of this line, been different, I could not exist. Other lines, of course, also enter into a family line along the way (my grandmother was Irish, while my mother was Bohemian-Czech on both sides). My family appears in Joliet, Illinois, before homesteading in Iowa. No Homestead Law, no Schall.

We cannot do anything about our already given genetic structure. Scientists now seem to want to manipulate our genetic side to eliminate defects or to make us blonds or geniuses. Odds are that we best leave the begetting process alone.

When we come to terms with our past, we see that it is made up of many chance encounters that took place because of wars, immigration, or accidents whereby this person met that person. In spite of this background of chance, we hold that the soul of each person is created directly by God.

And it is this soul in this body that constitutes our individual existence. The mind we have is a power of our souls whereby we know more than ourselves. Indeed, we seem to exist in order to know, to know the truth.

The oracle tells us to “Know thyself.” Aristotle and Aquinas tell us to know everything else also, or at least as much as we can. We soon realize that many people know more than we do. But the least talented of our kind also are created for the same purpose that we are, for eternal life.

What does this imply, this existence we have midst the myriads of existences in other human beings? We know that we are involved in the lives and deeds of others, as they are in ours. So we also exist in order that others might exist. It is here that the issue of our living the truth of our existence arises.

We know that divine providence is not defeated by our sins. It simply regroups, as it were, to bring good out of it. But it is quite clear that our existence falls into a “plan,” as St. Paul called it, that could not be what it is if we did not exist as the peculiar “I” that constitutes Schall or any other person as a singular, unique person in himself.

Can we conclude anything from these curious reflections? Though we may not know fully now the details of our existence, we will. And we will discover that we were initially created precisely to accept God’s invitation. The lives and loves of others would not have been possible without our unique, irreplaceable part in the divine plan.

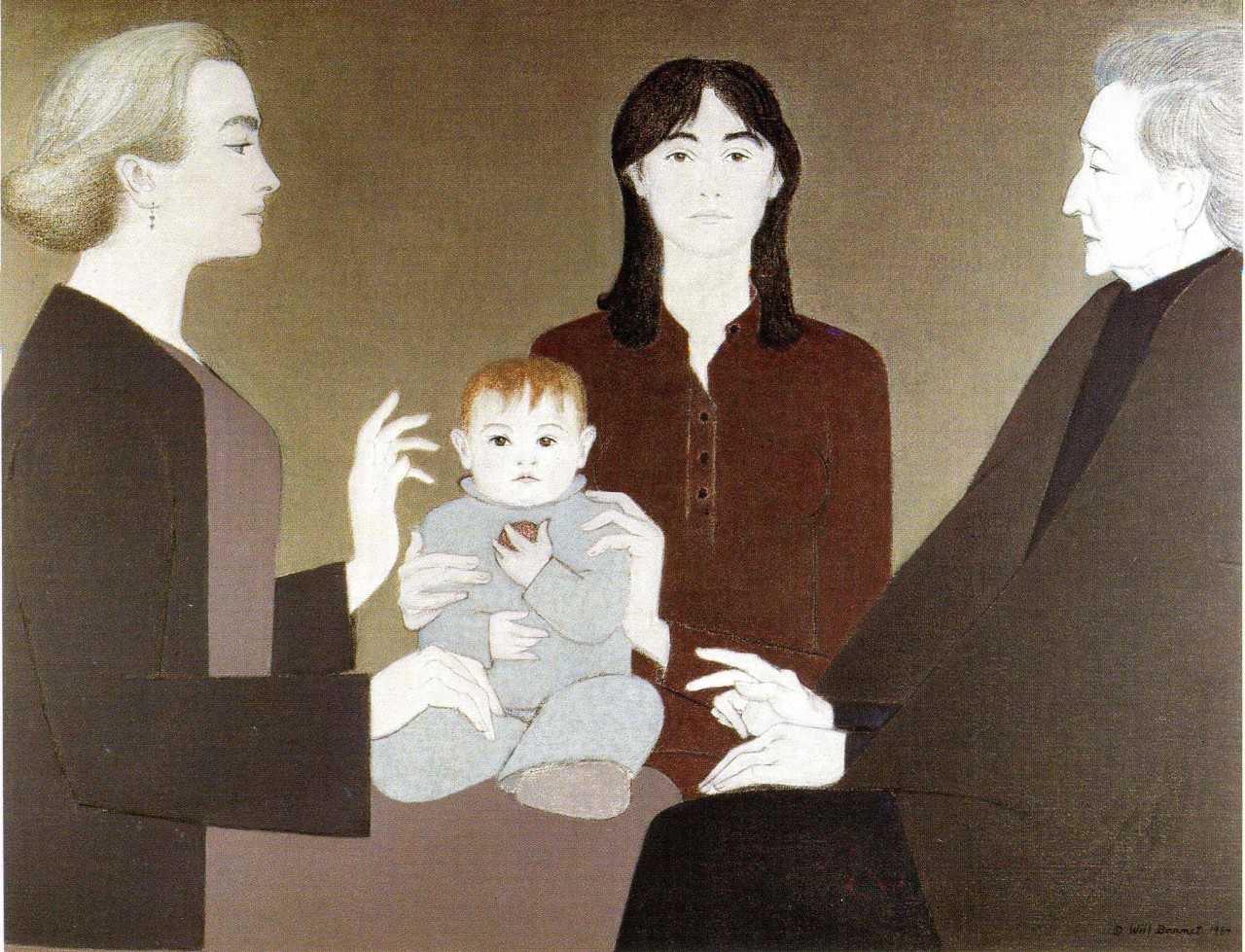

*Image: Four Generations by Will Barnet, 1984 [Collection of Contemporary Art, Vatican Museums, Rome]. Mr. Barnet was born in Beverly, MA and spent most of his life working and teaching in New York City, where died in 2012 at the age of 101.