The high point of American civilization was surely February 6, 1971. That was the day when a man played golf on the moon. We had landed there before and done experiments, and so on. But men will always find a way of playing golf.

The funny thing is that the astronaut (Alan Shephard) who smuggled onto the spacecraft the telescoping 6 iron, smuggled along with it not one but two golf balls. He had allowed himself, in advance, a “mulligan”! Which in the event he needed. He hit the first ball “fat,” more like a lunar bunker shot. But the second he got clean. “It went miles and miles and miles!” he exclaimed jubilantly, like a kid.

You can find that video, like the video of Neil Armstrong’s first steps, on the Internet. The quality is not good. Video live streaming from the moon back then was like Samuel Johnson’s dog walking on two legs: the marvel was not that it was done well but that it was done at all.

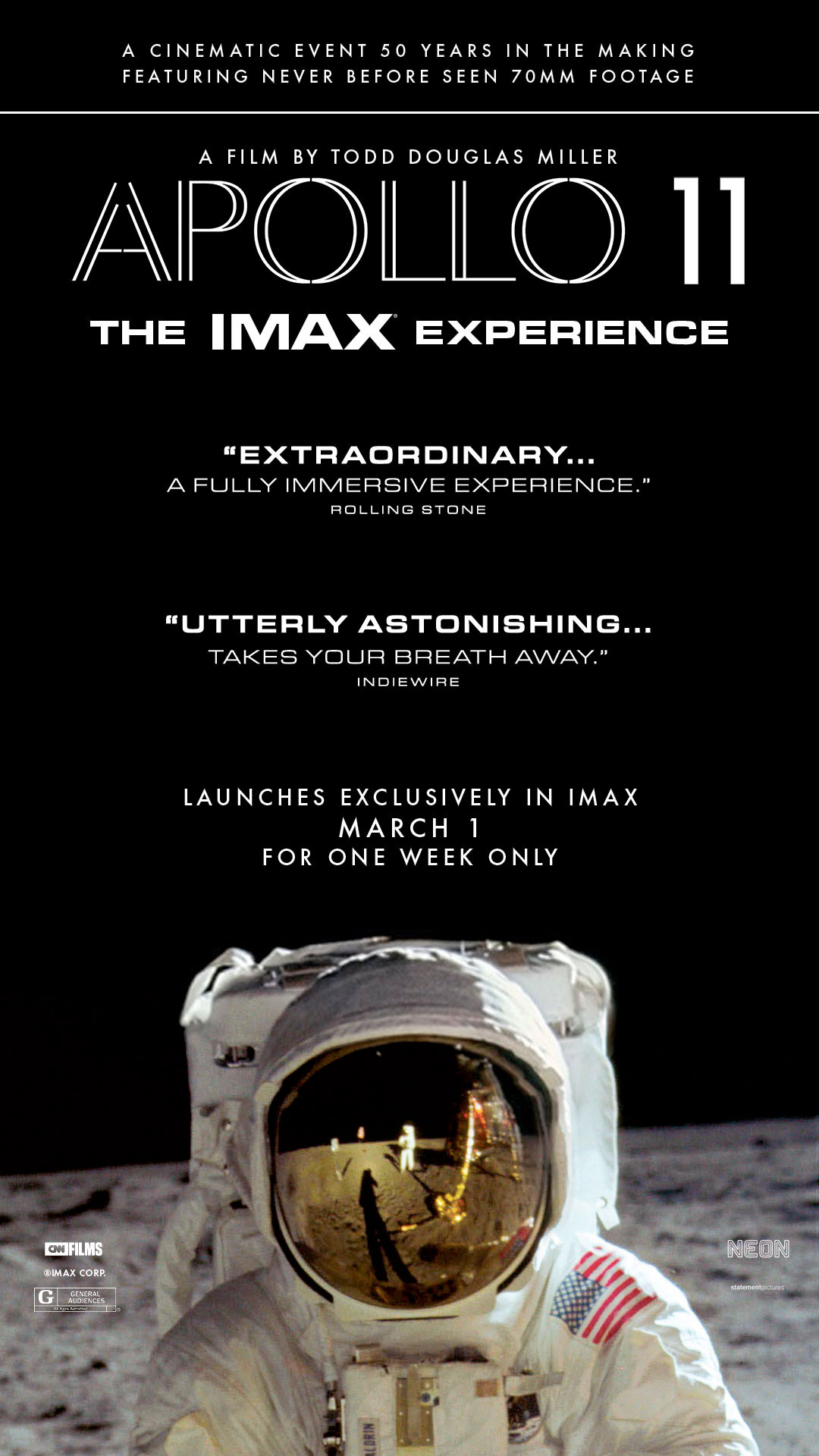

But it turns out that everything else about the original moon mission, called “Apollo 11,” was filmed meticulously by over 200 high-quality 70mm cameras. The filming was mainly to help the engineers, but incidentally for historical purposes. The documentary film which opened in theaters last Friday, Apollo 11, consists almost entirely of expertly edited footage from those great cameras.

The movie is strange for a documentary, as it has no narrator, no flashbacks, no setting of context, no background explanations, no panning over still photographs Ken Burns style. It begins with preparations for the launch and ends with the astronauts back on Earth in quarantine.

Yes, the narrative is helped by the occasional voiceover of Walter Cronkite, the famous TV anchorman, and the live working-language of the astronauts and control-room engineers. But mainly the subject matter is so fascinating and gripping that no additional narration is needed.

This is one of those movies that genuinely needs to be seen in an IMAX theater or equivalent. You need a three-story screen to get some sense of what it was like to witness a Saturn V rocket being transported by tractor from the assembly hanger to the launch pad. Some scenes are simply incredible.

The stage separations of the rocket in flight: what kind of telephoto lens can make it seem as if you are in another rocket flying alongside that one? The launch blast as filmed from immediately below the engines: how did the camera not melt in that sun-like inferno?

The stupendous Saturn V rocket stood 363 feet tall and weighed 6 million pounds. My favorite scene was watching that 30-story skyscraper lift itself off the ground (it seemed to groan!) and then rise up and disappear into the sky.

The movie was made of course for the 50th anniversary of the mission. And yet, if I felt it right, the atmosphere in the theatre was not that of a commemoration. We commemorate something that we take ourselves to have done. To watch this movie is as if to be an onlooker, as some other country, foreign to us, accomplishes great things. We are so far distant from them that we do not even know what it would be to want to do something similar.

Some differences stand out as they would if one were traveling in a foreign country. In the crowd scenes, people naturally group themselves into families. There are markedly more children than adults. There seems a certain innocence of expression on people’s faces and in how they speak. There is a greater sense of public decorum, as for example, the engineers all wear white shirts with dark ties. The massive science and technology on display seems to be looked upon as if it is a common possession.

To be sure, some of these differences are ethically fraught: among the rows of engineers at their consoles, not a one is black, and only one is a woman. But the film presents no judgments about the underlying injustices, unlike, say, the movie Apollo 13, where the relatively frivolous status of the wives of the astronauts was an explicit theme. Thus, here too, the sense of a foreign country is only increased – since we are prepared to condemn a society only if we take to it to have some commonality with our own.

The film does end with a retrospective, of President John F. Kennedy giving his famous speech, where he challenged the nation to land a man on the moon before the decade was over. That was why it seemed significant back then that Apollo 11 had succeeded in July 1969. But Kennedy gave his speech in 1961, which provides a better key to understanding the movie.

America in 1961was only fifteen years distant from World War II, that is, it was far closer to that war than to us today. In hindsight, the space missions look like a continuation of that war. We had ramped up a powerful “military-industrial complex,” in the good sense, to win the war, after a relatively brief involvement.

What were we to do afterwards, with all of that accumulated expertise and power? Not fighting a “hot” war with the Soviet Union. The space missions, then, belong to that other nation, which had something else to do after defeating the Nazis and Japanese imperialists.

Or consider it in this way. America in 1961 was less than 100 years distant from the Civil War. But the nation has lived half that span since Apollo 11. Ask then: in our own time, have we accomplished half of what we accomplished in the span from Manassas battlefield to Tranquility Base?

Are Facebook and the iPhone our great contributions? Is turning Harry into Sally our great cause?

And would any astronaut today imitate Buzz Aldrin (second man to stand on the moon and a devout Presbyterian) – and take Holy Communion with him to consume on such an awesome occasion?

What are we doing, where are we going, who are we? “Why are you standing here staring into heaven?” (Acts 1:11), the angel asked. The questions may be seen there, but not the answers.