The great upheavals of religious and theological knowledge over the last two centuries began with the question of how to read Scripture. The new science of geology seemed to call into question a literal reading of Genesis, which seemed to date the earth as about 6,000 years old. Then, along came the historical-critical endeavors of the German Higher Criticism, and the books of the Bible fell to pieces – thousands of them, fragments by various hands drawn together over centuries, so that Holy Scripture seemed to be a patch job and less than the sum of its parts.

How could you determine a meaning when every book was a weave of earlier, perhaps conflicting intentions? How could you trust what was given, if the book did not seem to be providing reliable historical data by which to pin down places and dates?

To readers of the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries, that last question seemed far from silly. Divinity exams from that period – I’ve seen them – include questions such as, “What was the date of Noah’s flood?”

But to those of us who have read T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, it seems odd indeed. The poem consists of 432 lines, of which at least 100 are full or partial quotations from various sources. That does not stop us from discovering coherent meaning in the poem; to the contrary, the poem gains in depth and significance by Eliot’s deliberate inclusion of other voices. If Eliot could do it, so can God.

Jewish and, later, Christian interpretations of Scripture have traditionally and consistently been “figural” or spiritual. By that was meant that, yes, every work has its literal sense, meaning in some cases, a historical event occurring, and in every case, the meaning intended by the author writing. But, every work also has its spiritual sense, a figural meaning that likely is not intended by the author, but which can be discerned within the author’s words and is generally of far greater significance.

Only in this way does Scripture become prophetic and revelatory, teaching us something we could not have learned for ourselves, and calling us to sudden conversion. Only in this way can we read the Old Testament as pointing to Christ as its fulfillment. And conversely, only in this way can we read Christ Himself as the lens through which to interpret the words of the Old Testament and the book of nature.

We can hardly understand either Testament without the spiritual sense, for the most cursory reading of any passage reveals an economy of language made possible only by a density of meaning: if you are not willing to unpack each sentence like a steamer trunk, then you are not ready to read.

Two of the greatest theologians of the twentieth century spent their careers trying to help the Church recover this way of reading Scripture – and, no less, of reading the world. Henri de Lubac’s four-volume Medieval Exegesis is concerned with describing the practice of figural interpretation as it had historically been practiced. It can seem a bit odd to read what you might call a historical-critical defense of figural interpretation; what de Lubac mostly did was outline a brief but elegant theory and then multiply quotations from the Church Fathers until it became clear that his theory was theirs.

Hans Urs von Balthasar was a bit more sanguine and ambitious than de Lubac. He too could multiply quotations, but he also just went ahead and interpreted Scripture – and the rest of history – in spiritual terms. De Lubac wanted to restore interpretive authority to the Fathers of the Church; von Balthasar wrote like a Father.

This has not stopped the Church from remaining concerned that many believe that historical criticism is the only “scientific” way to read Scripture and that, to modern man, figural interpretation just looks arbitrary or silly.

I’ve spent the better part of two decades reading and writing about figural exegesis, and actually practicing it. But all thought of theory flees when I consider just two moments from the last several years.

One summer, I decided to read St. Augustine’s The City of God, often called the great saint’s masterpiece, and it surely must be if you judge by sheer length. For most readers, it will be of uneven interest compared with his Confessions, which – to me – is the singularly perfect book of our tradition outside Scripture.

I find much to admire in City and much that changed me, but mostly in a scholarly sense. I am impressed by how Augustine developed or refuted some aspect of classical thought on his way to showing us the truth about things.

But, late in the book, indeed during a long stretch that would tempt most readers to abandon ship, Augustine describes Noah’s Ark. He patiently describes the dimensions of the Ark, the position of the door in its side. And then he shows us that it is proportionate, at great scale, to Christ’s own body, whose own side would pour out water and blood from its pierced doorway.

Christ is our Ark, carrying us through the rough seas of a world flooded by sin. To read this was not an occasion of thoughtful approval, but joy; not reflection, but conversion. “Yes,” I thought, “that is my Lord and my Christ!”

A few years ago, I was reading my children The New Catholic Picture Bible, a wonderful adaptation. We came to the story of Abraham and Isaac. Abraham receives his command from God to sacrifice his son. Isaac himself carries the wood up the hill that, unbeknownst to him, is intended to become the pyre of his own immolation. An angel intervenes to spare Abraham this great test of his fidelity, and the text explains:

Isaac carrying the wood up the mountain is a picture of Jesus who carried His cross up the hill to Calvary, to offer himself for the sins of the world. Although God saved Abraham’s son, for love of us He did not save his own Son from death.

Yes, yes, yes! Isaac anticipates Christ; the son bearing wood is a prophecy, a type, of the Son bearing the Cross. I felt myself draw nearer to God and enter into his mystery even as the kids sat there in my lap.

A couple of months later, I was recommending that Bible to another father with young children, and I mentioned this figural interpretation. He immediately replied, “How is it that anyone doubts that Jesus is Lord?”

That’s how figural exegesis works; it doesn’t take us back to a particular historical moment. It allows God to reach out and grab us by the lapels – and shake us into faith.

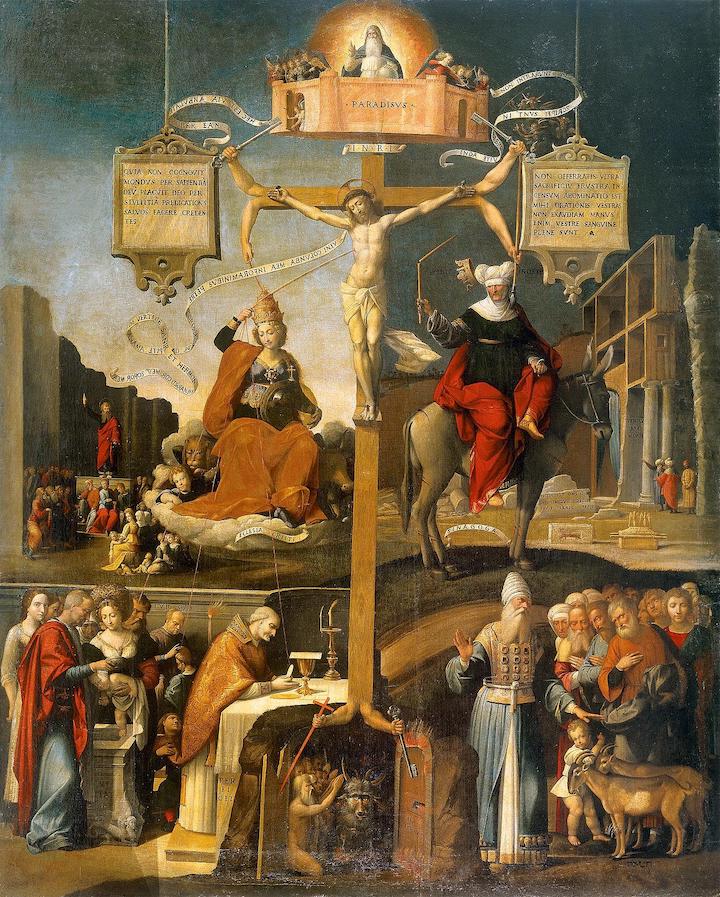

*Image: Allegory of the Old and New Testaments by Benvenuto Tisi, c. 1530 [Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia]