The Schall Effect

Robert Royal

The passing of Fr. James V. Schall S.J. on April 17 – our esteemed colleague and dear friend – is, in everyday human terms, a very sad event. But it would be profoundly un-Schallian to think of it only in terms of sorrow because, as the great man knew better than any of us, when we die we go to live under God’s love, mercy, and justice – which was why we were created in the first place. That end is and ever shall be the proper remedy for all our earthly sorrows and injustices, especially death.

That was a central lesson from Plato that Schall often repeated: if the evils we have suffered are not righted in eternity, then the world would be founded in injustice. But it isn’t, and our whole Catholic tradition, which he studied and taught and labored (to an almost superhuman degree) to develop further to meet the challenges of our time, should lead us to think about this life and the next one in ways almost diametrically opposed to the usual secular view. As he repeatedly argued, many modern woes stem from our lost of the truth of “what is,” and our failure to live according to that truth.

I believe it quite likely that the good padre, having been immediately given the Beatific Vision, has already been assigned a room now in the heavenly mansions. And as soon as he unpacked his things, went off to continue the conversation with the souls of Augustine and Aquinas, Romano Guardini and Joseph Pieper, Solzhenitsyn and St. John Paul II (and if it’s allowed up there, even with the great pagans like Plato and Aristotle, Cicero and Seneca, and many others). He belongs in their company. It would come as no surprise to hear that he was even lecturing the angels now on how better to understand our current predicament – and better help us.

Are there books in Paradise? I don’t know that any theologian or mystic has ever given a definitive answer to the question. But if there’s anything that we might imagine the new arrival having to get used to, it may be the absence of reading material. And as his editor for over a decade, I wonder what he will do instead of writing.

I had lunch with him (and the also estimable Fr. Kenneth Baker, S.J.) in January at the Jesuit retirement house in Los Gatos, California. He was as lively as ever and went on and on about a thick book – he held up two fingers, far apart – someone had sent him on Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

I’m about a quarter-century younger than he was and still have both eyes (he lost one during an operation over a decade ago). And I’d think, more than twice, about the eyestrain involved. He plunged right in, even knowing full well that his remaining days on earth were few.

Other commenters today – some former students, others colleagues, still others intellectual collaborators (one non-Catholic) – remind us of his rare personal qualities, the steady good humor in the face of medical ills, the courage in facing challenges not only in the world but within the Church itself, the seemingly effortless ability to remain interested in everything from the NCAA brackets to Christian persecution in remote parts of the globe, even as his health deteriorated. (I offered my own personal reminiscences late last year at the Institute for Catholic Liberal Education dinner where he was given the Rabboni Award, viewable here.)

Like Brad Miner (see below), at my age, I don’t pay much attention to praise or blame – both often misconceived. But I was touched when a friend told me Schall had described me as an “entrepreneur of the normal.” Given that Schall really knew what was normal and why it mattered, it stuck with me, and has spurred me to try to do better ever since.

He had that kind of effect on everyone. Over the years, I never heard anyone say a bad word about him. And no wonder: A good man, good friend, good teacher (to many, not only those formally his university students), good scholar, good priest, in short a good Christian.

God grant him his proper rest and reward now – he certainly never slowed down in his efforts to bring us all greater light and joy, despite age and infirmity. And God grant that we who were deeply touched by his life may continue, in our own modest ways, with the work that he carried out so brilliantly and faithfully.

His Praises Mattered

Brad Miner

I first met Father Schall in the 1980s at gatherings in New York and in Washington, D.C. He was in his early sixties and I in my early forties. At one point not long after, I asked him to contribute to a book I was writing, The Concise Conservative Encyclopedia, and he did a brief essay, “The Christian Tradition,” that traced the development of Christian political thought from the New Testament through Augustine, Aquinas, and Pius XI. The first sentence was classic Schall: “Two dicta of conservative thought are: (1) Preserve what is worth saving; and (2) To preserve anything worthwhile, some change is necessary.” Schall was a preservationist.

With the advent of the Internet came the advent of email, and with the advent of The Catholic Thing came the advent of much email correspondence between Miner and Schall.

Anybody who has ever read much of Schall (and, if you’ve been with TCT for the last decade, you’ve read him every other Tuesday) knows of his passion for Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle: together one half of the Athens-Jerusalem nexus that is the source of Western Civilization. Schall was a friend of those fellows. Thus, in his last lecture at Georgetown he could say, in the context of friendship and how it is gained and lost (“If we get that issue wrong, we will get life itself wrong”):

It is a sobering and, yes, exhilarating experience for a student to realize that the best thing ever said on this abiding topic was spoken, not yesterday afternoon, but twenty-five-hundred years ago.

Yet Jim, as he insisted on being called, was also a lover of Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip. As he wrote here in 2012, “Schall is not the first to maintain that Charles M. Schulz of Peanuts fame was a first-class thinker and theologian. He is easier to read than most philosophers and theologians. But that is a virtue provided one speaks the truth of things.” The impetus for this observation was a conversation between Linus and Sally in which the boy says, “Wouldn’t you like to have your life to live over if you knew what you know now?” Sally asks: “What do I know now?” And Schall adds: “Philosophers from Aristotle to Heidegger have asked the same question . . .” And then: “Keeping philosophy in a language that the layman could understand has been the vocation of many good philosophers.”

Schall always did that.

A few weeks before he died, he sent me a link to an essay he’d written for The American Scholar in 1996 titled “On the Death of Plato” in which he’d written this about the death of Socrates:

Some of these friends like Apollodorus, who was to recount The Symposium from Aristodemus, were already weeping. They showed thereby that they had not learned Socrates’ lesson, that philosophy was a preparation for death. When death is present, the philosopher is present. Was Plato ultimately the one follower of Socrates who understood this?

No, Jim. You did too.

Until he began writing to me – after almost every column I wrote for The Catholic Thing– I’d have told you I neither wanted nor needed anybody’s praise or encouragement – not at my age! But Schall showed that I did, although only from him.

Reason and Revelation

Hadley Arkes

In the early 1980s, I was on an extended leave from Amherst College, visiting at Georgetown. One unanticipated gift of that stay was that Jim Schall would be my new colleague, and that would become an enduring blessing.

I would take long walks with Fr. Schall through the bricked paths of Georgetown, and we would think aloud, together, on some of those questions in political philosophy that we were both trying to think through – and find a way of explaining to students. When I finally came into the Church, in 2010, Fr. was with me, to concelebrate. And curiously, it was Fr. Schall who kept me a “live” presence at Georgetown, for he was the only member of the Faculty who would teach my books, long after I was gone!

One of the things that we were fascinated to think through were the teachings of my former professor, Leo Strauss, on the tension between reason and revelation. John Paul II would come to write critically on this matter in Fides et Ratio, but long before that, Fr. Schall had managed to say some of the most sensible things that could be said. As he put it, “Revelation can be articulated because it contains logos.”

As it turned out then, both revelation and reason were accessible only to one kind of creature. That creature had the wit to sift between the claims of revelation that were plausible and implausible. “If what is said to be revealed is irrational or contradictory,” wrote Schall, “it cannot be believed, even according to revelation.”

For Schall, revelation becomes open to us, on the most important questions, when it is opened by people who “study politicks,” as Samuel Johnson had it. For politics raised distinctly moral questions about right and wrong, the just and the unjust. But as Schall used to say, political philosophy points outside itself, and “leads to answers that are not specifically political.”

Such as what? Perhaps to the ground of consolation, when innocent, good people suffer, and when evil succeeds. Or when we raise the question, perhaps, of what the meaning of it all finally is. With those questions we touch the spiritual part of our lives, a part that may distinctly be informed and sustained by revelation.

But as Schall said, revelation alerts us to the possibility that our true home will really be elsewhere: “Ironically,” he wrote, “it turns out that we will not understand the world if it is only the world we seek to understand. [And] we often suspect, at our highest moments, that in being in this world, we are not made only for it, dear as it can seem to be.”

Looking ahead to that world, Fr. Schall used to end every note to me by saying, “Pray for me, Jim.” And I ever will.

Confident in God and the Logos

Daniel Mahoney

Father James Schall left us at the age of 91, reading and writing and sharing his considerable insights right to the end of his earthly life. As others have observed, he had survived so many illnesses that he seemed indestructible. It was a joy to be on his e-mail list where he shared his writings (and those of many others) with a wide array of family and friends. He never lost interest in the things of this world (even writing a bi-weekly column for The Hill) even as he displayed supreme confidence in the promises of God.

And there was no one who had more confidence in the reason, the logos, at the heart of things. He was deeply influenced by Leo Strauss’s recovery of classical political philosophy in our time, but he did not share Strauss’s austere insistence that faith and reason ultimately belonged to two different spheres.

Schall particularly loved Pope Benedict XVI’s 2006 Regensburg lecture, in no small part because it helped restore a fuller appreciation of the amplitude of reason in the light of God’s creation. Schall, like Benedict, opposed every form of theological and political voluntarism or nominalism. He did not believe that God or Allah could change the nature of reality, or invert the meaning of good and evil.

Like Pope Benedict, Father Schall saw more than a few affinities between the Muslim mind at its voluntaristic worst and the willfulness at the heart of contemporary Western thought. Schall spoke often of an “order of things,” natural and supernatural, and knew that grace could not do its work without the most profound respect for “what is.”

Father Schall was an exemplar of thoughtful orthodoxy, someone who embodied the best traditions of the “Catholic mind.” He knew Aristotle and St. Thomas by heart (but not by rote as in the old manual learning), and he wrote lively, engaging, and discerning essays in the tradition of his heroes, Dr. Johnson and G.K. Chesterton. His book lists, found in so many of his works, pointed his numerous readers to the most accessible sources of Christian and classical wisdom.

This is why Another Sort of Learning (Ignatius Press, 1988) remains something of an underground bestseller, providing a liberal education, at once serious and exhilarating, for those who can no longer find it in the universities or in the official circles of the Roman Church.

Schall was also something of a dissenter: he knew radical environmentalism would keep the poor poor, that the poor are not poor because the rich are rich, and that pacifism was coextensive with nihilism and neglect for the civic common good, and not authentic Christian wisdom.

He never conflated Christianity with softness or cowardice, moral laxity, or that falsification of the Good which is the “religion of humanity.” He did not “kneel before the world” or genuflect before fashionable but ultimately destructive ideologies.

For all who want to hear Father Jim’s voice in all its wisdom, humor, and humanity, turn to At a Breezy Time of Day: Selected Schall Interviews on Just about Everything, recently published by St. Augustine’s Press (whose Editorial Director Bruce Fingerhut thought Father Jim the C.S. Lewis of our day).

May our dear friend take comfort in the company of angels and the grace of God, our Father and friend.

Daniel J. Mahoney holds the Augustine Chair in Distinguished Scholarship at Assumption College in Worcester, MA.

Irresistibly Lovable

Wilfred M. McClay

Fr. Jim Schall was one of the most irresistibly lovable people I have ever known, and my life was greatly enriched by knowing him, and having a little bit of his metaphysical good cheer rub off on me.

His gratitude to God for the very fact of his existence was not just a platitude, but a pervasive lived reality, a persistent radiance that even the dullest and most resistant observer could not help but notice. Even with all his medical struggles, especially with his vision, there was always an irrepressible cheerfulness about him, an atmosphere of joyous surrender to the fact that the miracle of it all is bigger than any of us.

Generations of Georgetown students fell under his spell of this charming man from Pocahontas, Iowa. So did I.

I got to know him through the good offices of another irresistibly lovable man, the late Michael Cromartie of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, an evangelical whose good humor mirrored Jim’s and whose improbable friendship with Jim was something he wanted to share. I’m so glad he did.

I remember hanging out with the two of them at a reception for Touchstone magazine, and then our being joined by Justice Scalia – who was, among other things, one of the great stand-up comedians of our time – and then the ensuing twenty minutes were filled with such nonstop hilarity that I thought my stomach muscles might never recover from all the laughter.

It is hard to be too solemn in remembering Jim, he just wouldn’t want it that way.

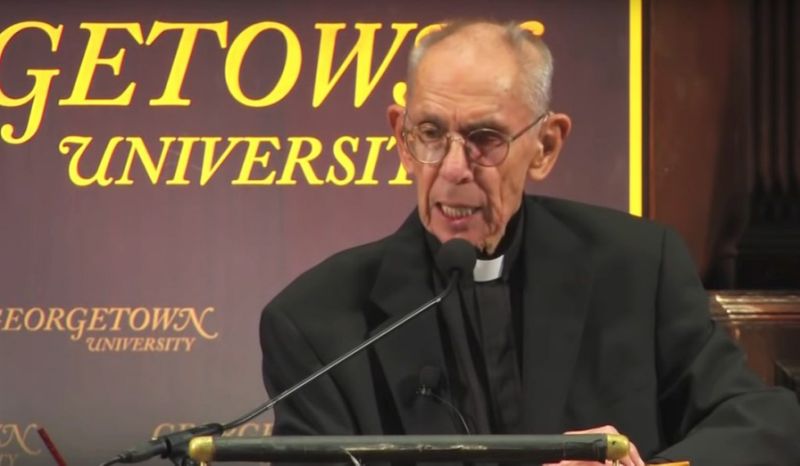

I was never his student, at least not in any formal way, but I had been at many events and panels with him over the years, and was one of the many admirers who trekked to Washington and crowded into Healy Hall on the Georgetown campus to hear his last lecture in December of 2012.

It was an electric occasion, full of poignant moments, and the place was packed. Everyone present knew, without it having to be said, that this marked the end of something more than Jim’s teaching career. It was the last moment in a certain era in the life of Georgetown University.

To ring a change on Holmes’s famous description of FDR, Fr. Jim had a first-rate intellect, but an even more excellent temperament, and his ability to connect profound ideas with the world of nitty-gritty experience was a part of what made him such a great teacher.

In him, the insights of Plato and Aristotle were mirrored and magnified in the endless supply of personal anecdotes he could deploy, drawing on a surprisingly earthy understanding of everyday life in modern America.

And his love of Chesterton and of Wodehouse, far from playing the role of comic relief in his outlook, was part and parcel of his love of the world, in all its absurdity and topsy-turvy surprise.

In his insistence upon the “unseriousness” of human affairs, he pointed toward a seriousness far deeper than “the purpose-driven life” that preoccupies so many Americans. Instead, he pointed toward the purpose-less life, the life that Josef Pieper extolled, in which we set down the tools we compulsively employ to “improve” our lot, and instead yield ourselves happily and gratefully to the immensity of what God has in store for us.

His happiness was infectious, and even as I write this remembrance, I cannot sustain my feelings of sadness for very long, without feeling a smile creep onto my face as I remember him. I think he would approve. In fact, I know it.

Wilfred McClay is the G.T. and Libby Blankenship Chair in the History of Liberty at the University of Oklahoma, and author most recently of Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story (Encounter, 2019).

Gratitude, Pure and Simple

Cynthia Searcy

Among the hundreds (thousands?) of essays Fr. James Schall published over the years, his own favorite was “On the Death of Plato.” As he so often did, he begins the essay with a quotation, this one from Cicero’s On Old Age:

But there is another sort of old age too: the tranquil and serene evening of a life spent in peaceful, blameless, enlightened pursuits. Such, we are told, were the last years of Plato, who died in his eighty-first year while still actively engaged in writing.

Nothing else could so succinctly sum up the last years of Fr. Schall’s earthly life.

In the days since he went to his eternal reward, I have re-read some of the tributes in honor of his retirement that students submitted to The Hoya, the campus newspaper at Georgetown University. Most of them ended on a note of gratitude for having known Fr. Schall, and for teaching them to be attentive to what is. Gratitude, pure and simple, is the only response to the life of a great man like Fr. James V. Schall.

Among the many things for which I will always be grateful, he alerted me to the English writer Evelyn Waugh. A passage in Waugh recently jumped out at me as I was reflecting on Fr. Schall’s life, particularly his priesthood. Just two years before his own death, Waugh wrote:

I am old now but when I was young I was received into the Church. I was not at all attracted by the splendor of her great ceremonies – which the Protestants could well counterfeit. Of the extraneous attractions of the Church which most drew me was the spectacle of the priest and his server at low Mass, stumping up to the altar without a glance to discover how many or how few he had in his congregation; a craftsman and his apprentice; a man with a job which he alone was qualified to do. That is the Mass I have grown to know and love.

In my student years at Georgetown, Fr. Schall very rarely said public Masses. I always thought that was curious, since the priesthood was so clearly the animating principle of his life. In the later years of his life, however, when I would visit him at the Sacred Heart Jesuit residence in Los Gatos, he would invite me to participate in his Mass every day (as a congregant, not an altar server). Needless to say, this was a privilege of the highest magnitude, and it revealed a side of Fr. Schall that I had not known in our years of friendship.

He was a Jesuit through and through, and though he wouldn’t dream of intentionally violating a rubric, he was not fussy about liturgy. I think a lot of people who knew him through his writings assumed, understandably, given his love of tradition, that he must have been a partisan for the Tridentine Mass or that he revelled in especially high liturgies. That was far from the truth. He said a Mass of great simplicity, in the plainest of vestments. His homilies were always brief. They almost always included references to Plato and Leo Strauss.

Fr. Schall might have protested too much that he was an Aristotelian-Thomist, since Plato was never entirely out of his thoughts. In his last lecture at Georgetown, “A Final Gladness,” he remarked “[I]n some sense, it is all right to die, as Cicero also taught in his treatise On Old Age. The only thing that is really serious is not death, but God, as we read in Plato’s Laws. All else is unimportant by comparison. This idea was revolutionary to me.”

A dear friend pointed out to me that my memories of Fr. Schall would be more poignant during the liturgies of Holy Week. This was absolutely correct. Fr. Schall suffered cheerfully through many agonizing physical maladies in his life. As a priest, he knew that the drama of Holy Week and the triumph of Easter is what life, his life, was all about – and that death is not, ultimately, serious.

Cindy Searcy graduated from Georgetown University in 2004 with a BA in Government. She is the Vice President of Development at the Catholic Information Center in Washington, DC.

Holy and Lovable Father-Priest

Scott Walter

As we friends of Fr. Schall mourn his death, I suggest we reflect on how friendship is the key to his life in three ways.

First, there are his deep friendships with so many – the Burleighs, the Jacksons, his numerous family members and his devoted former students like Cindy Searcy. These personal friendships extended to countless colleagues and to thousands of students over the years, many of whom would exclaim enthusiastically, “I’m majoring in Schall!”

Second, we should recall that philosophic reflection on friendship is one of his most important, recurrent subjects. You find him, for instance, ending his 1968 book Redeeming the Time with it, and it’s also the culmination of his 1996 tome At the Limits of Political Philosophy.

He insists that friendship is critical along two dimensions, so to speak, horizontal and vertical, or worldly and otherworldly. Horizontally, Schall taught that friendship is the enemy of tyranny in this world. This private form of love, which binds us so powerfully together, is despised by tyrants who want to destroy the private realm in order to see and control every human thing, weakening all ties we have except our ties to the regime they rule.

Vertically, Schall observed that this world’s deepest thinkers have pondered whether the blessings of friendship could ever reach to friendship between man and God. Aristotle explicitly raises that question and concludes that the inequality between God and man renders friendship impossible. But, Schall observes, this impossibility could be “overcome if God became man,” and what indeed does our incarnate Lord tell the apostles at the Last Supper we just celebrated? “No longer do I call you servants. . .but I have called you friends.”

Here we arrive at the third and most critical way that friendship is the key to Schall: All his mountain of writings, all his connections to so many thinkers, colleagues, students, and friends, all his work as a priest guiding Christ’s flock and celebrating the sacraments instituted by Christ – everything that he did and all that he was (for being, he insisted, matters far more than any doing) flowed from his own deep friendship with the Lord whose Resurrection we celebrate.

Read, for instance, his marvelous (and alas, timely) essay “On Building Cathedrals and Tearing Them Down” (in The Praise of ‘Sons of Bitches’: On the Worship of God by Fallen Man) and discover his delight in hearing the first Mass at St. Mary’s Cathedral in San Francisco – and his longing that “there would be Masses for a thousand years” in this “glorious” shrine.

Or read his pamphlet “Journey Through Lent,” which ends with his emphatic endorsement of something William Blake wrote: “I have tried to make friends by corporeal gifts but have only made enemies. I never made friends but by spiritual gifts, by severe contentions of friendship and the burning fire of thought.”

Now much as Fr. Schall loved beautiful cathedrals and “the burning fire of thought,” we must immediately add that he endorses Blake’s next thought, which descends to a more homely level: “He who would see the Divinity must see him in his Children.”

This Schall manifestly did every step of his life. I saw him once befriending a camera crew who had come to film an interview with him and then doing the same with the cab driver who arrived to take the crew away.

Even more I think of an incident as he and I descended a large stone stairway at White Gravenor Hall after class, deep in conversation over Plato. Just ahead of us, a lass began sobbing on the landing, no doubt after some treacherous youth had dumped her there. Schall instantly dropped Plato and was at her side, consoling her and taking her away for a private talk.

I think as well of the multiple baptisms he attended for Erica and my babes. He was the soul of friendly merry-making at the receptions afterward, but he always arrived early and sat in a back pew before Msgr. Watkins began the ceremony, clearly sunk in meditation with his greatest friend of all.

Meditating on the glory of cathedrals which every year celebrate the resurrection of the body, Schall in his essay demanded to know, “How do you call man out of his everyday routine and narrowness?” I only know that that is exactly what this holy and lovable father-priest did for me, one of his innumerable children who owe, under God, our Faith to him.

Scott Walter is president of the Capital Research Center. He first had Fr. Schall in spring semester 1982.

To Remember Schall . . .

Joseph Wood

To remember Schall, we must read Schall, and read what he read.

As Fr. Jim prepared to move to California to the Jesuit retirement house in Los Gatos that had once housed his novitiate, he moved most of his library to Christendom College. He described what a significant decision this was for a scholar: how to dispose well of a large library collected – and read and carefully considered – over the course of a lifetime of learning.

He chose to retain for his room in retirement the works of five thinkers: G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, C.S. Lewis, Monsignor Robert Sokolowski of the School of Philosophy at The Catholic University of America, and Dr. David Walsh of CUA’s Politics Department.

Of the many reading lists he had offered in his books over the years, this was his own final list for reading and re-reading. If there was to be, as he quoted Belloc in his final lecture at Georgetown, “no final gladness” in this life, these authors would provide the joy of knowing as much as we can know, and asking about the rest.

I wish also to point out an essay that should not be lost in the vast body of Fr. Jim’s work, a 1994 piece (later reprinted in The Imaginative Conservative) entitled “On the Place of Augustine in Political Philosophy: A Second Look at Some Augustinian Literature.”

This essay, challenging to the reader but accessible with the effort Fr. Jim would demand of any searching student, is spectacular in its combination of Schall’s range of sources, his inquiry into political philosophy, and his central concern of what it is to be a human person. Along with his final lecture, this should be high on the list for anyone who wants to know Schall, or know him better.

David Goldman, a mutual friend, described Fr. Jim’s presence among us as kiddush haShem, a sanctification of the name of God.

Deo gratias.

Joseph Wood teaches at the Institute of World Politics in Washington D.C. and is a Fellow at Cana Academy.