Exactly forty years ago I had the wondrous experience of discovering the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice. The Scuola di San Rocco (“School of St. Rocco”) is one of the numerous lay confraternities founded by rich patrons during the Middle Ages and Renaissance to support charitable outreach to the poor.

“Scuola” also refers to the majestic building that served as meeting room and chapel for the brotherhood. And it houses the splendid series of paintings, created over a period of twenty years, by the Venetian genius Jacopo Robusti, better known as Tintoretto (1518–1594). He undertook this herculean task – sixty paintings, of extraordinary size and complexity – “to demonstrate the great love that I bear for the saint and our venerable school, because of my devotion to the glorious Messer San Rocho.”

It is scarcely possible to take in the sweep of Tintoretto’s vision in a single visit. But even a first encounter overwhelms with a sense of almost tangible artistic originality wedded to profound religious faith and devotion. No wonder the sometime artist and fulltime adulator of Michelangelo, Giorgio Vasari, could say (perhaps begrudgingly) of Tintoretto that he had “the most extraordinary brain that the art of painting has ever produced.”

For those for whom a trip to Venice may prove a ponte too far, the National Gallery in Washington has mounted a superb exhibition to commemorate the five hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth. The exhibition will run through July 7. And admission is free!

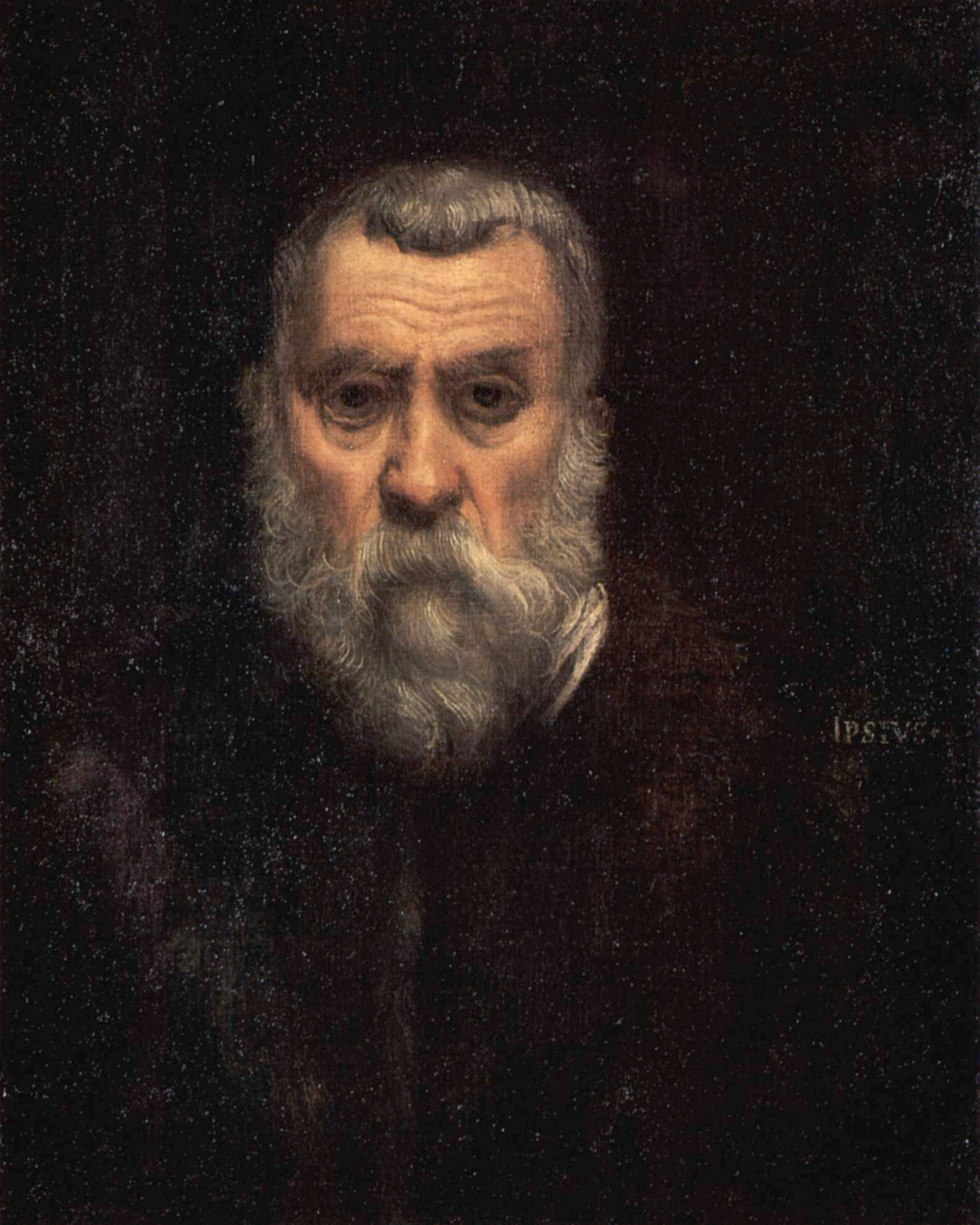

Forty-six paintings reveal the depth and breadth of Tintoretto’s art: religious scenes, of course, together with mythological episodes, where the naked human body is as celebrated as it was by Michelangelo, who was an admired exemplar for Tintoretto. Remarkable portraits – including two stunning self-portraits – anticipate Rembrandt and Velazquez. The first self-portrait dramatizes the assertive and determined young artist; the other depicts the chastened, almost transfigured old man. Together they serve not only to bookend physically the exhibition; they unveil a moving spiritual journey, what Dante called “un moto spiritale.”

One painting that I lingered long over, even contemplatively, is the artist’s portrayal of the Baptism of Jesus. The theme is a commonplace in Venetian art where the Jordan evokes associations with the city’s circumambient sea. But there is nothing commonplace about Tintoretto’s rendition of the scene in this late painting, an altarpiece for the Church of San Silvestro in Venice.

The gracious interaction between the Lord and his herald resembles a spiritual “pas de deux.” The artist’s kinetic choreography verbalizes in motion Jesus’ humble acquiescence that “all justice must be fulfilled.” (Mt 3:14-15), while John’s generous gesture acknowledges that Jesus “must increase, while he himself must decrease.” (Jn 3:30) The light radiating from Jesus illumines John who still stands partly in darkness, bearing witness that “the true Light has come into the world.” (Jn 1:9) Without doubt, we have here a striking foreshadowing of Caravaggio’s “tenebrism.”

Fine as the range of artworks on exhibition is, one critic has pronounced that the final self-portrait of the seventy-year-old Master would alone merit a journey to Washington. It is this portrait that the painter Édouard Manet proclaimed “one of the most beautiful paintings in the world.”

The painter stands before us devoid of artifice; exposed; a palpable presence. But presence of what? One viewer sees here only sadness and suffering, resignation. Yet I think this too passive a reading of a work of such surpassing genius. Another discerns fear in the features of an old man approaching death. This too fails to do justice to one of so passionate a faith, far transcending a merely cultural Christianity. A third, much closer to the mark, sees a face “mysteriously cognizant.” But cognizant of what?

Might I suggest: cognizant of truth – truth beyond the masks and defenses we daily assume.

It is said that the young philosopher Edith Stein spent an entire night of awe reading the Life of Teresa of Avila. At dawn, she closed the book and remarked simply: “this is truth.” That night marked the beginning of her spiritual transformation, culminating in The Science of the Cross and her willing sacrifice for her people.

I thought of Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross as I contemplated Tintoretto’s self-portrait. The man who painted the Light that shines in the darkness painted himself enlightened: purified of illusions – illusions of fame and fortune, of rivalry and revenge.

This “beautiful painting” bears no trace of the superficial or the sentimental. In the whole course of his spiritual journey, Tintoretto was cognizant of the poor, both as a member of the Confraternity dedicated to their service and in the commissions he undertook, often accepting minimal fees from simple associations of laborers. Now he has himself become poor, shorn of pretense and superfluity. And never was his inner self so richly portrayed.

*Image: Tintoretto’s The Baptism of Christ, 1589 [Church of San Silvestro, Venice]

**Image: Tintoretto’s Self-Portrait, c. 1588 [National Gallery, Washington, D.C. on loan through July 7, 2019 from Musée du Louvre, Paris]