Senator Bernie Sanders, seeking the Democratic party’s presidential nomination for the second time, repeats often what has become his signature applause line: “Health care is a right and not a privilege.” This sentiment resonates with many voters who will cast ballots in the upcoming Democratic primaries.

It is also consistent with Catholic social teaching. The Church has consistently reaffirmed the right to healthcare in the era of modern medicine. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that: “the political community has a duty to ensure . . . in keeping with the country’s institutions . . . the right to medical care.”

Recognition of this human right is logical and consistent with a proper understanding of the role of the state in promoting the common good. A primary responsibility of properly ordered governance is to foster the conditions that allow for the protection and development of the family and its members. Without medical care, some people cannot fulfill their responsibilities to members of their families or make use of the full range of talents that would contribute to the well-being of the broader community.

Effective medical care is rightly a matter of common, society-wide concern. Some diseases are contagious, which means communities have an interest in the good health of all of their members. Political leaders should be held accountable for promoting public health because government agencies are the only entities with the capacity to coordinate a response to certain medical challenges and threats.

And emergency care, like fire-fighting, is something that requires communal coordination and financial support; otherwise, it would not exist. The principle of subsidiarity means that lower levels of government can and should play an important role in matters that involve localized, rather than national, health concerns.

The right to medical care exists in a framework of other rights and responsibilities. People have a right to medical care, yes, but also to education and employment opportunities that allow for the caring of one’s family. Political leaders are responsible for determining how to allocate societal resources so that all of these needs are addressed well and fairly, with special attention to making sure those with the least resources are not left behind.

No society, however, can be expected to provide all things to all people in all circumstances. Personal responsibility necessarily plays an important role in all of these matters.

As Sanders has repeated his “health care is a right” mantra over the years, he has been able to goad some Republican politicians and conservative analysts into taking the opposite position. Sanders’ critics usually note that the Constitution does not confer such a right, which is true. They also argue that designating health care as a right would compel a governmental response that could make health care worse under certain circumstances.

Those are losing arguments. The right to medical care is not found in the Constitution, but that’s true of other rights. Sanders veers off course, however, when he says that his preferred solution – “Medicare for All” – is the only way to ensure that all citizens and residents have ready access to needed care.

That’s certainly not the position of the Catholic Church. The Church has no expertise in how the particulars of a health system should operate. And there are many ways the state can carry out this responsibility. Medicare for All would have the federal government run a single health insurance plan for all Americans. But there are other options, including approaches that rely more on consumer decisions and market principles. For example, Switzerland uses a mix of public regulations and private incentives to ensure its population has insurance and can get services when needed.

With Medicare for All, the federal government would set the payment rates for all medical services, using Medicare’s complex payment regulations as a starting point. Those payment systems have many flaws. They underpay many providers and overpay others. They are rigid and difficult to amend or fix because moving changes through Congress, or even through the federal bureaucracy, is a political process, with interested parties influencing the outcomes.

Placing all payments for services within a governmental process also risks creating supply problems. Elected leaders in democracies usually operate on timeframes of two to five years, while investments in a health system can take much longer to show positive results. In the short-run, physicians and hospitals have little choice but to accept the payments imposed by the government as full reimbursement for their professional services, but over longer periods of time price cuts can lead to the flight of personnel and investment capital out of the health sector and into other industries. The result is less innovation, lower quality, and quite possibly fewer practicing physicians.

While there are reasons to be wary of Medicare for All, the status quo in the U.S. is also unacceptable. The vast majority of Americans are enrolled in health insurance and can get the medical care they need, but premiums for that coverage are high, as are prices for services and prescription drugs. The system is also maddeningly complex for patients to navigate, with heavy burdens of bureaucracy and paperwork. The nation’s network of hospitals, physician groups, clinics, and other providers of services is capable of delivering the best medical care in the world, but it is also fragmented and inefficient.

The current system also fails to adequately protect some citizens with extremely limited personal resources. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded eligibility in the Medicaid program to households with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line. Medicaid is jointly administered by the federal and state governments and covers the poorest Americans.

After a Supreme Court decision in 2012, the ACA’s Medicaid expansion was deemed optional for the states. Currently, 36 states and the District of Columbia have expanded their Medicaid programs in accordance with the ACA’s provisions, but 14 have not. In the non-expansion states, there are 2.5 million people with incomes below the poverty line who are not eligible for Medicaid and who also are ineligible for subsidized private insurance, which begins at the poverty line.

Provision of medical care in the U.S. also suffers from a lack of cost discipline. The government’s regulatory controls do not keep costs in check, and the incentives for cost reductions in the private sector are weak or nonexistent.

Opponents of Medicare for All have an obligation to present to Americans reform plans that would correct the flaws in today’s system without resorting to full governmental control. That’s possible, but it requires making changes and compromises that both conservative and liberal-leaning lawmakers may find uncomfortable.

For starters, all Americans living below the poverty line should be eligible for Medicaid coverage. For better or worse, there is no practical alternative to providing coverage through Medicaid to poor households; and trying to do so would be a waste of resources and political energy. Republicans in Congress and in the non-expansion states should compromise with their Democratic counterparts and adopt a solution that closes the gap for those poor families who remain ineligible for the program.

Although cost discipline is possible through better consumer incentives, governmental action is still required to allow the market to function better. Health care has features that lead to market failures unless the government helps support a rational consumer role. For instance, patients are heavily dependent on the expertise and judgments of their physicians, which makes them less willing to act as autonomous consumers when seeking medical care. The government can help correct for this and other inherent problems with guardrails that make room for consumer discretion while still ensuring patients get the right services no matter what choices they make.

Federal subsidies for insurance enrollment could be converted into defined contribution payments instead of support that increases when consumers select more expensive coverage. Consumers would then have an incentive to enroll in lower-cost plans, to avoid out-of-pocket costs for themselves. The plans they would choose from would be regulated and provide the same set of covered services. Less costly insurance plans would be attractive to price-sensitive consumers.

Reforms of this kind are needed throughout the health system, in public insurance (including Medicare and Medicaid), and in private insurance, particularly as provided by employers. Without them, costs will continue to rise, which will lead more Americans to believe the only answer is to authorize the government to impose blunt cost controls as a last resort.

Senator Sanders’ is correct that health care is a right, but that only gets him so far. The tougher question is how to put in place programs and processes that ensure all citizens can get the services they need to stay as healthy as possible. Different countries will necessarily have different answers to that question based on their varying cultures and historical experiences.

But at the moment, the U.S. system falls well short of what should be acceptable for a wealthy country.

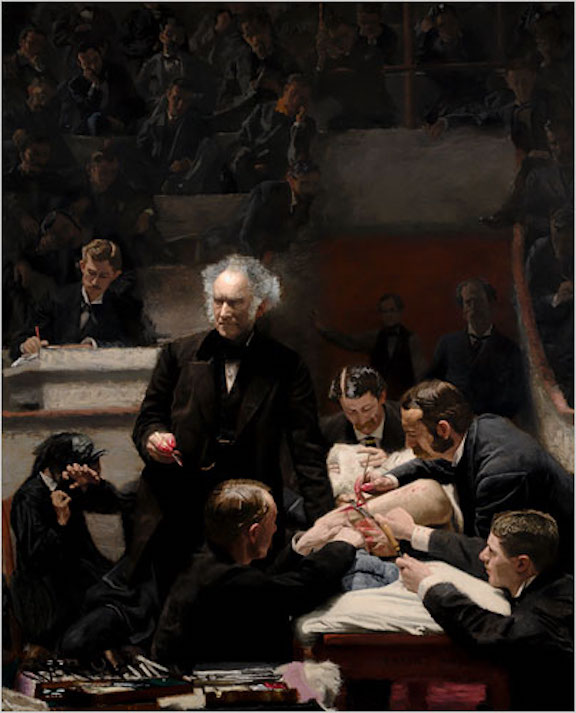

*Image: Portrait of Dr. Samuel Gross (The Gross Clinic) by Thomas Eakins, 1875 [Philadelphia Museum of Art]