My wife and I are museum rats. We spend a lot of time in museums when we travel and a lot when we stay at home – home being the New York City metro area. New York City itself is home to about seventy art museums (plus many others devoted to science and industry), and the greatest of these is the venerable MET: the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Fifth Avenue between 80thand 84thStreets.

The MET is one of the largest museums on earth and the third most-visited (after the Louvre in Paris and Beijing’s National Museum of China) – 6,953,927 visitors last year to be exact, of which those 27 must be the Miners. Our MET membership pays wonderful dividends.

“Museum” comes from the Greek, mouseion – the seat of the Muses – and nearly every museum I’ve ever visited has been an inspiration. A great museum is a close cousin of a great cathedral, with similar echoing footfalls and hushed voices. Your eyes are pulled to every compass point, and there are occasions of awe.

The MET collection includes 2,000,000 works of art, so it would take you something like a century to see everything, although, even then, you’d probably be rushing too much through each daily visit.

From the standpoint of The Catholic Thing, the MET offers a treasure of 406,000 hi-res digital images of works in its collections – 1,700 from its holdings of European paintings – not a few of which have illustrated our columns over the last decade.

If you’ve visited, you know that, from Fifth Avenue, you walk up three tiers of granite steps to enter the museum’s Great Hall. If you go straight ahead and to the left or right of another great set of stairs, you come to the MET’s collection of medieval art. And it was here, on our most recent visit, that I was struck with the thought that there would not be an art museum on the scale of the MET (or the Louvre) were it not for the Catholic faith. The MET even has a sister museum, the Cloisters (set on a hill overlooking the Hudson River), devoted exclusively to medieval European architecture, sculpture, and decorative arts, pretty much all of it from when pretty much all of Europe was Catholic.

To be sure – as the MET itself proves, its collection being so multiculturally vast – you could have a very fine museum devoted to art that included nothing inspired by Jesus Christ. But it would be a much smaller museum.

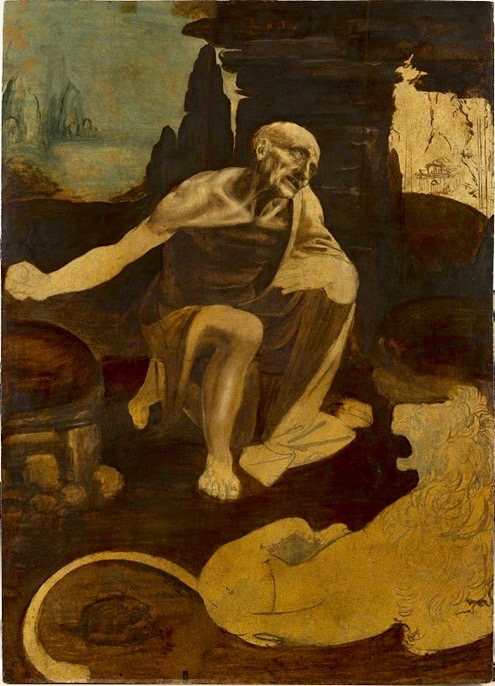

On a recent visit, we walked through the Great Hall to Gallery 955 for a members-only preview of a single, unfinished painting by, arguably, the greatest artist of all time, Leonardo da Vinci – his Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness. The c. 1480 painting, on loan from the Vatican Museums, will be on display at the MET until October 6th. The exhibition is timed to coincide with the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death.

In its collection, the MET has more than three dozen other works depicting St. Jerome, and it has a number of drawings by Leonardo, but it does not have any paintings by him, which is why when Max Hollein, Director of the Met, says, “We are thrilled to honor Leonardo da Vinci’s legacy by displaying this rare and exceptional painting,” you know he means it. (The Louvre, by the way, has six Leonardos!)

St. Jerome was born in the Roman province of Stridon, Dalmatia (modern-day Albania) in about 350 A.D., give or take, and became a Christian in his early teens. As a young man, he read widely and studied diligently, but also lived a life not unlike his contemporary, Augustine of Hippo, which is to say he may have indulged in some sexual excess.

When he awakened more deeply to Christ, and seeking desert penance, he left Europe and settled for a time near Antioch, where – among other things – he began his study of Hebrew, tutored by a Jewish convert to Christianity. In his early thirties, he was ordained, began further Scripture studies with Gregory Nazianzen in Constantinople, and then became secretary to Pope Damasus I in Rome.

It was the pope who encouraged Jerome to create a Bible in Latin, which quickly became the versio vulgata, the version most accepted and widely used, the Vulgate. And Jerome’s translation of the Old Testament was done in large measure using Hebrew texts, not Greek. For these and his other scholarly writings, which in volume were second only to St. Augustine’s in their era, Jerome was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Boniface VIII in 1298, along with Augustine, Gregory the Great, and Ambrose of Milan, saints one and all.

Da Vinci based his Jerome on The Golden Legend, a hagiographic work, originally written by blessed Jacobus da Voragine, c. 1260, and amended over the centuries by others. Among a number of likely apocryphal elements is the Legend’s story of the saint’s befriending a lion. Leonardo also conflates Jerome’s period of desert penance with the end of the saint’s life. After all, it’s a tableau.

Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness also shows a lot about da Vinci’s process. As the MET explains: “Leonardo did not proceed in a wholly disciplined way. He was particularly interested in creating a detailed, anatomically correct under drawing for the saint’s ascetic body.” It’s well known that Leonardo often reworked his canvases, fussing his way towards unattainable perfection. He is also famous for starting, abandoning, and painting over canvases, and we’ll never know how many da Vinci paintings remain undiscovered.

Among the fascinations of Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness is Leonardo’s “signature,” which in this case is his thumbprint. I joked with friends, including a former cop who served on the NYPD-FBI joint task force on organized crime, that the Bureau should put Leonardo’s prints through its IAFIS database. If any Renaissance figure might have discovered time travel, it would have been Leonardo, and it would be no surprise to discover he hasn’t “kept his nose clean,” let alone his thumbs.