The things that we could pray for are far more extensive than those we do pray for. What is the reason for this?

Here’s an example of what I mean. I have known a holy priest who, when a pope dies, asks people to start praying, right away, for graces for the next pope. “Who that person is, is known to God,” he has said. “It is some definite, living churchman. We can start praying for him now, just as we prayed for the last pope when he was alive.”

This seems right. And yet, we could have started praying for that next pope even before the earlier one died, but we didn’t. Moreover, we could pray for all the men currently alive who, known to God, will become pope, not simply the man who will become the next pope. Until the world ends, there will always be several men like that.

For instance, after the death of Pius XI in 1939 there were seven future popes, known to God, alive on the earth: Eugenio Pacelli (b. 1872), Angelo Roncalli (b. 1881), Giovanni Montini (b. 1897), Albino Luciani (b. 1912), Karol Wojtyla (b. 1920), Joseph Ratzinger (b. 1927), and Jorge Bergoglio (b. 1936). People could have prayed in this way, and yet they did not.

Future persons, in general, are like that. Your ten-year-old daughter, assuming she does not have a religious or celibate vocation or fails to find a husband, and assuming that, God willing, she lives to adulthood, will almost certainly marry someone who is alive today. Who that person is, is known to God.

We could pray for him, and maybe you are moved to do something like this, even as you read these words. But typically we don’t. Or if we do, we are praying that she meet and marry someone suitable.

Praying for the past seems like this too. If we can rely upon God’s knowledge of the future to pray for someone whose identity is outside human ken (the living man who will be the next pope), then why can’t we rely upon God’s knowledge of the past, to pray for what happened in the past – since for God past and future are an eternal present?

Your twenty-year-old son who was not practicing the faith and who died last year in a car accident: can you pray now that he was given the graces then to turn to God in his last moments? This is not to pray that his soul in purgatory be released into heaven, but to pray for the gift of a good in the past. It seems that you can, and maybe should.

We have the example of saints. In an earlier column, I pointed out that St. Thomas More assumed that people in the future could pray meaningfully for him while alive. But then, these are exceptions that prove the rule, because praying for the past is so rare.

I want to say: there is an order in prayer, and we do not pray as “extensively” as we can, because it would be outside of God’s order for us. Prayer is and is meant to be matched to our experience of time and place, which is centered principally on oneself, here and now, but extends outwards by association.

The first petition in the Lord’s Prayer is like that: “Give us this day our daily bread.” People point to the “us” and say that the prayer is not self-centered. But one might equally point out that “us,” as a first-person pronoun, is more self-centered than it needs to be.

The petition is not “Give everyone” or “Give to members of the Church” or “Give to everyone who asks.” The reference point of the petitioner is primary. And what we ask for today is bread simply for today. “Sufficient to the day is the evil thereof.” (Mt. 6:34) And so too, apparently, is the good thereof. The day is the natural unit of prayer for the present.

We don’t pray for all the future popes alive today because it would be disordered to so. In the life of prayer as well, there is “a place for everything, and everything in its place.” When we pray for “the living man known to God who will be elected the next pope,” if the prayer is intelligible, we are praying specifically that he have the graces to accept the burden of the Petrine ministry and to act with wisdom from the moment he is elected.

There is a place for that prayer in particular: the time that the holy priest suggested. That time matches the prayer, and some other time is matched to some other prayer.

I draw two lessons from these reflections.

The first is that if we take seriously the “order in prayer” that, I argue, God intends for us, then we will take times and places of prayer more seriously.

1. That wedding that is difficult and costly to attend? But it’s the time and the place to pray for that marriage in particular.

2. Or consider how St. John Paul II led the whole Church to see that the arrival of the new millennium was something other than an accident of the base-ten number system.

The second is that we have a clear interpretation of the Christian’s office to be constant in prayer (Rm. 12:12). We are not told to “pray for everything” but rather to “pray always.”

But this is to see how prayer is meant to be matched to the time, and not to leave any time unmatched with its prayer: matching a “please” and a “thank you” to a gift, matching praise to the praiseworthy, and matching cries for assistance to the work, as in the old prayer: ut cuncta nostra oratio et operatio a te semper incipiat, et per te coepta finiatur (“that each of our prayers and works may ever take its start from you and attain its end through you”).

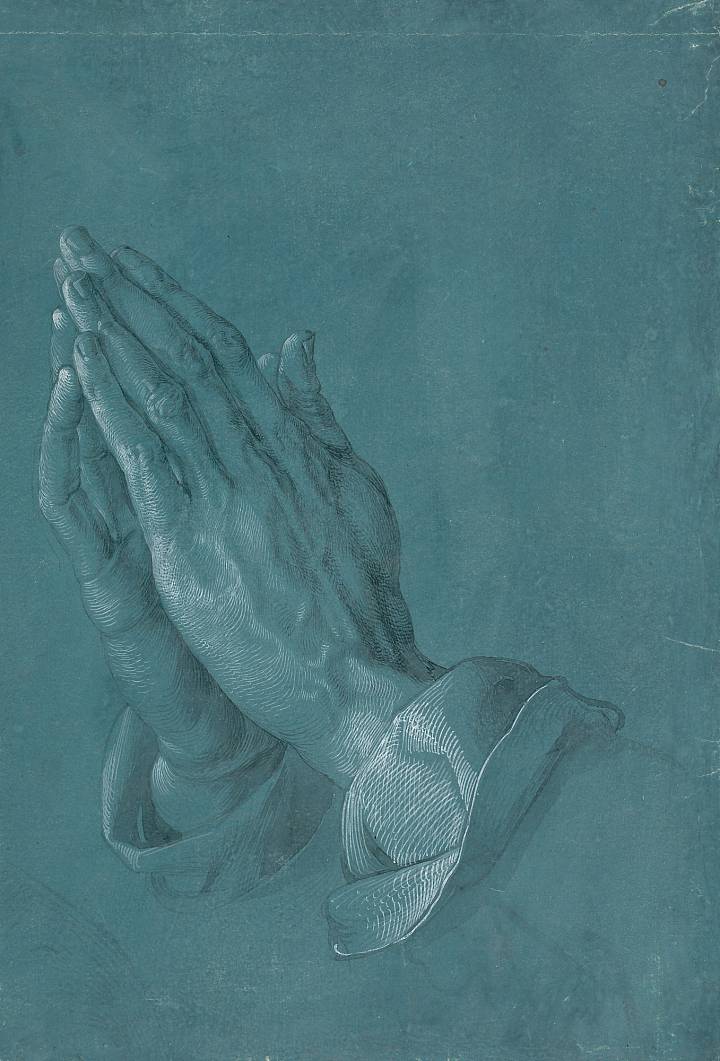

*Image: Praying Hands by Albrecht Dürer, c. 1508 [Albertina, Vienna]