I will answer my question shortly.

First let me describe the instructions for kneeling at Mass, in the diocese of Antigonish, Nova Scotia, where we live during the summer. These may be summed up thus. Outside of a portion of the first half of the Eucharistic prayer – from the calling down of the Holy Spirit to the elevation of the chalice – there is to be no kneeling at Mass.

Tonight, as usual, I was ready to fall to my knees at the end of the Sanctus, when I saw the whole congregation standing still, so it looked as if my legs had buckled under me for a moment while I jerked myself upright again, waiting for the instructed time.

Then everybody duly knelt. But as they’re not in the habit of kneeling before Mass. That meant that the Eucharistic prayer was punctuated by dozens of clop-clops, as the kneelers hit the floor. Every church up here seems to use the shortest of the prayers, so we spend about ninety seconds on our knees, and then we all stand for the acclamation, with another chorus of clop-clops, as the kneelers are raised, never to be set down again.

That is, we don’t kneel after the Agnus Dei. And the bishop has told us that we aren’t to kneel once we return from Communion. Everyone is supposed to remain standing in place until every single communicant has received, as a sign of solidarity or something.

Since that takes a long time, and since most of the people in the pews are old, it means that after the last person has returned to his place, everyone sits down. There is thus no sense of prayer right after your reception of the Eucharist.

You are watching the lines thin out. Two or three minutes have elapsed, and if you were thinking about the Eucharist while you walked up to receive, you are probably not thinking of it now, because looking around at everybody else has distracted you.

While you sit, the priest is up in the sort-of-sanctuary pottering about with the vessels and saying the requisite prayers. The Body and Blood of Christ are still there, and you are sitting at ease.

I don’t sit, not then. I kneel and try to pray. It isn’t the easiest thing in the world to do, because the piano player is tinkling away, and I know that I’m conspicuous, but I figure that the people surely remember the distant days when they too knelt and prayed after Communion. They can figure that I’m an American living here in the summer, so I’m just not aware of the custom of the country.

When does a man kneel if not in church, or in prayer at his bedside? Never. Then why should kneeling be placed under sufferance, the less of it the better? When liturgical innovators tore out the Communion rails, what did they do to the human side of the experience of Communion?

I stand in line to receive, just as I stand in line for chili and doughnuts at Tim Horton’s. Indeed, at the latter, I may have a few moments of silence for thinking, but at Communion, no. Keep that line moving, pal. Body of Christ already.

The priest at this church is a very fine man, and he gives intelligent homilies. I believe he does the best he can, by his lights, under the circumstances. But everything in that Mass, from the music out of Glory ’N’ Praise, to the bored and slouching altar girls, to the chirpy announcer, to the disgraceful lectionary, to the bleak and bare walls, to the bad liturgical instructions come down from the chancery, acts as a drag on the ship of faith.

It is like trying to sail with anchors down and flukes in the mud.

What is a liturgist? Someone wholly innocent of anthropology; numb to the meaning of bodily gestures and the tones of human voices; ignorant of the subtleties and the many registers of language; a blank for solemnity; with no sense of drama, no feeling for silence; someone whose idea of poetry may be found on a greeting card; someone who will lay on your back the burden of a sham hospitality; someone whose very smile sends all deep thought and feeling into an abyss of indifference.

How else to explain the ineptitude? How can they not see what they have done? It is one thing to stand next to someone you don’t know, or you do know and don’t like. That happens all the time. It happened in high school when you lined up to go to your lockers. It happens at the bank, at the airport gate, at the Department of Motor Vehicles.

It is another thing, and a rather disturbing thing, to kneel beside the stranger or the enemy, and to feel that perhaps he is not a stranger or an enemy after all, but a confused and suffering human soul, as you are.

I do not feel close to strangers who are compelled to turn to me and smile. I do feel close to the person kneeling beside me at the Communion rail – boy or girl, man or woman, young or old. There we are together, waiting for the approach of the priest who brings us the Lord.

How could liturgists have missed the obvious power of such an experience? But perhaps they knew of that power, and they wanted us not to feel it.

Sometimes I imagine what it might be like to return to a Catholic Mass after forty years of sin in the desert. You have memories of solemnity. You are about to do a fearful and serious thing. You are ready to encounter the power of God. And then you walk through the doors.

You may feel more comfortable than you expected to feel. But you did not go there to feel comfortable. Will you return?

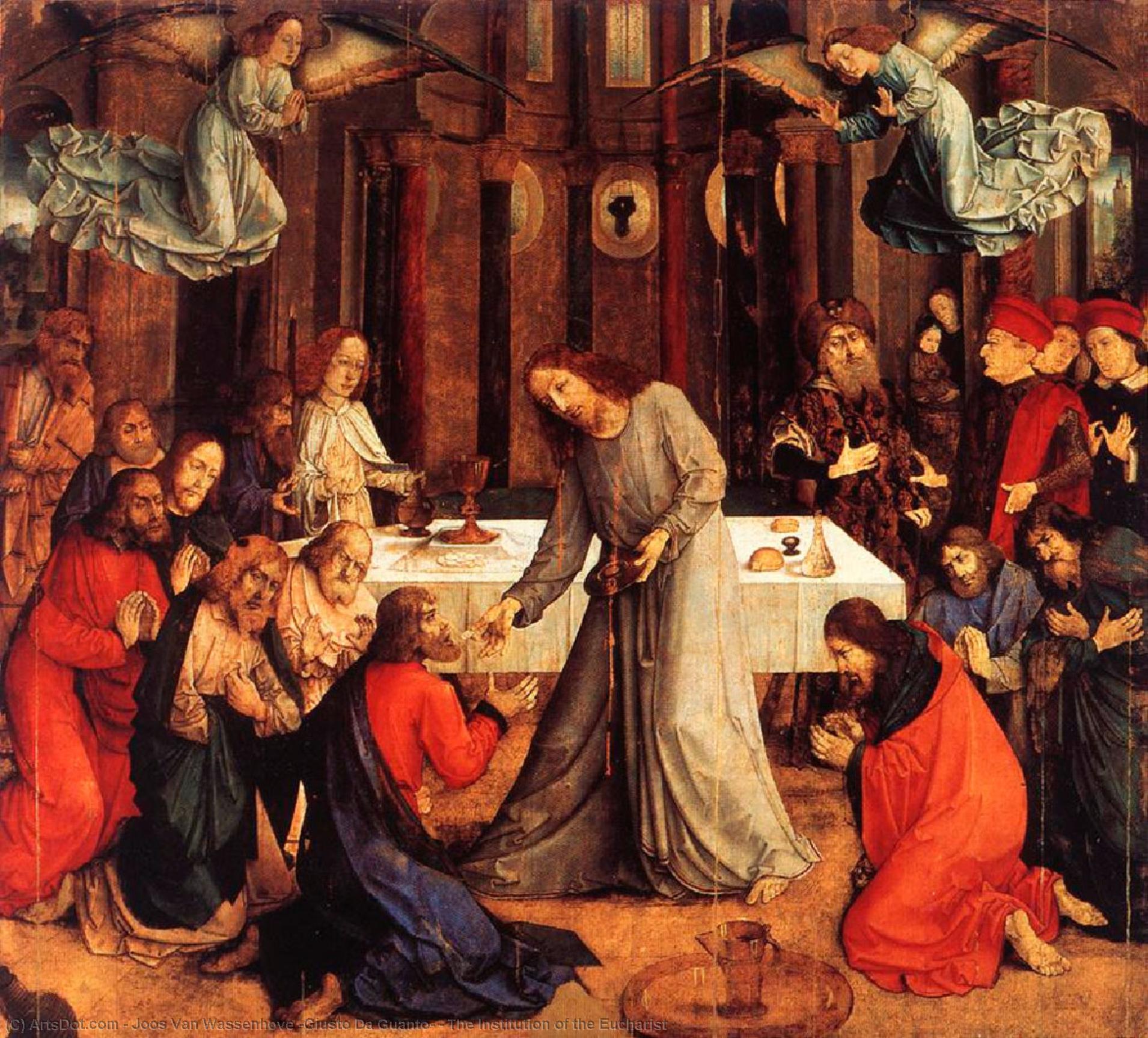

*Image: Communion of the Apostles or The Institution of the Eucharist by Joos Van Wassenhove (Giusto Da Guanto), 1474 [National Gallery of the Marches, Urbino, Italy]