If someone was wondering how many minutes he should exercise daily for good health, you might know the answer (30 minutes). But if you didn’t, you wouldn’t doubt that there was an objective answer. And you’d have an idea where to look for it (e.g. the U.S. Dept of Health).

You’d understand that that number was a minimum. Someone who needed to lose weight, or an athlete in training, would need to exercise a lot more than that. But you’d grasp this idea of what, objectively, “the average person generally needs for good health.” To live well means to build at least 30 minutes of vigorous activity into your daily schedule. We all sense this and know it implicitly.

But I want to pose the corresponding question for the soul. We say that there is a soul, and that the body in many ways represents the soul. There is activity of the soul, and health and strength, too. So it seems we can ask: how many minutes should I exercise my soul each day for good spiritual health? Here, in contrast, although the matter is more important, we tend to think there is no objective answer, and we wouldn’t be sure of which authorities to appeal to, in order to answer it.

Note that I’m asking about time “we set aside.” There can be physical exertion which “goes along with” daily life – walking to work, lifting bags of groceries, etc. Living a more active life in this way is good. Just so, there can be acts of spiritual “exertion” in the ordinary activities of the day. But I am asking about times that are just for bodily exercise, and just for spiritual exercise.

Or approach it this way. You can distinguish in principle prayer from asceticism. Prayer may be defined as conversation with the Lord. Asceticism is any activity that requires and builds self-discipline.

In theory, there can be conversation with the Lord that does not require self-discipline. Many people seem to think of prayer primarily in this way. They think of conversation between friends as something like two men sitting in easy chairs smoking cigars and drinking scotch, carrying on a great conversation. And they picture prayer as like that, sitting in an easy chair having that kind of friendly chat with God.

In principle, too, there can be asceticism, of some kinds at least, without prayer. The philosopher Thomas Reid solved problems in the calculus every morning, for the mental discipline, before writing philosophy. The analytic philosopher Roderick Chisholm told me once that he studied an article of the Summa each morning before beginning work, not for what it said, but for the discipline of working through it.

Benjamin Franklin’s daily self-examination relative to his chart of virtues would be another example. A more frivolous example would be how some people solve sudoku and crossword puzzles to stay sharp.

But although prayer and spiritual asceticism are in principle different, in practice they seem to go together. Prayer is conversation with the Lord, indeed. But suppose the Lord is walking out to the desert: you cannot converse with him, then, without becoming shorn of everything else.

Or suppose the Lord is climbing a mountain, and to converse with him you must climb with him. Perhaps you have climbed mountains and know what degree of self-discipline is required to walk steeply uphill continuously for four or five hours. Yet Our Lord did give the examples of going out into the desert to pray, and climbing a mountain to pray. (Lk 5:16, 6:12). And it’s doubtful he gave us these examples without intending to show us something about the nature of prayer.

There are no examples in the New Testament, after all, of Jesus finding an easy chair to pray.

The mistake that you “find” time to pray seems bound up with our confusion that prayer is in practice separable from asceticism – as if praying will just “turn up” or prove itself to occur spontaneously. As if it just might turn out that climbing a mountain could somehow naturally intrude itself into your daily life: “I went to work, and finished those projects, and then climbing a mountain suggested itself as the thing to do.”

Prayer requires asceticism – because of original sin, because of the demands of discipleship, because of the power of the Cross. We can also marvel at how (although prayer is sought out of love, as conversation), it nonetheless proves itself to be a more effective means of developing spiritual self-discipline for every area of life. More effective than even direct ascetical practices (except for purely intellectual discipline – where calculus problems would probably be better).

Concerning our original question, then: How much time should I spend every day in prayer? We can answer that this would be the time, too, that one spends in needed exercise of the soul.

To this question, there does seem to be an objective answer, and competent authorities. When we look to the saints and great popes, we see that they recommend daily attendance at Mass (30 minutes); a daily Rosary (15 minutes); daily reading of the Gospel and a spiritual book (15 minutes); and daily mental prayer (at least 15 minutes but ideally one hour, as exemplified in the Holy Hour) – which comes to two hours. Apparently, to live well as a Christian means to build 120 minutes of prayer into your daily schedule

I wonder if, returning from a visit overseas, you’ve been astonished in the airport by how obese Americans are. Maybe, while you were thinking this, a team of collegiate athletes walked by, headed for their flight. I suspect if, as in one of Plato’s myths, there were judges who could see souls, they would similarly be astonished by how spiritually obese we all appear.

And Christians who should stand out like that team of athletes look just as obese as everyone else.

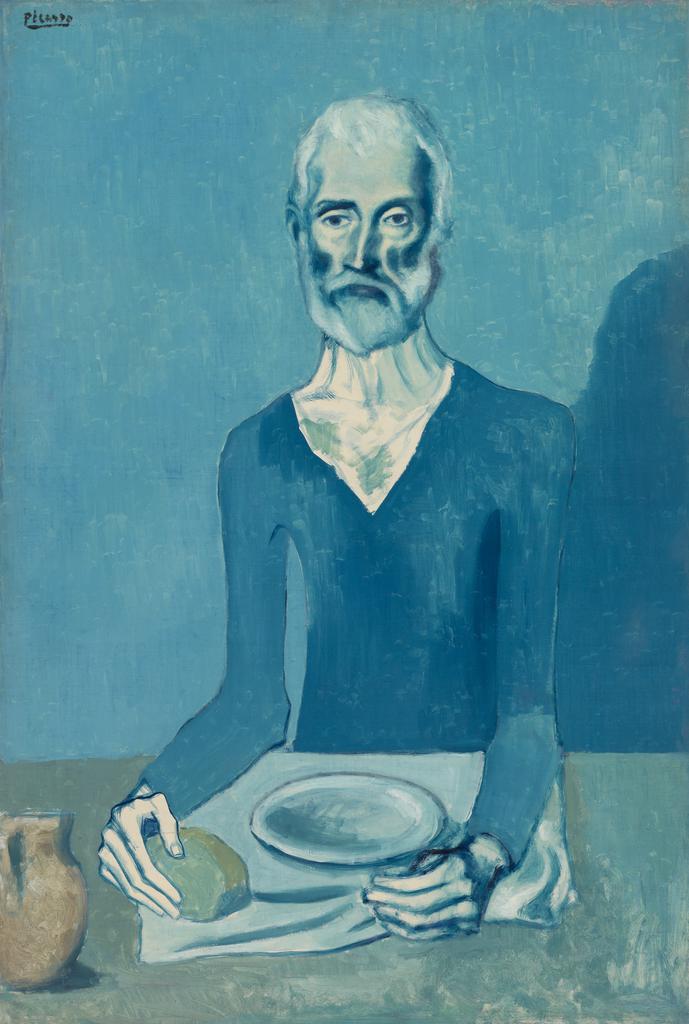

*Image: The Ascetic by Pablo Picasso, 1903 [Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia]