As Vladimir and Estragon, the nondescript protagonists of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, strive to prove their existence to themselves and to the outside world, they ask an unusual question.

“You did see us, didn’t you?”

If they can be seen, they reason, they must exist. Being seen as a form of self-validation is nothing new. The British aristocracy of the Georgian era knew that making an appearance at the Grand Pump Room of Bath was essential to their social relevance. And, in some sense, our selfie-culture is a desperate cry to be seen.

Beckett’s drifting bums instruct a messenger boy reporting to Godot, “Tell him that you saw us.” Sans action, or self-gift, or other-centered focus, they hope, by having been seen, to authenticate that they are indeed alive.

But being seen can have a much greater impact if one with eyes to see looks more deeply.

Nicholas Kardaras confronts our hunger to be seen in his watershed exposé: Glow Kids: How Screen Addiction is Hijacking Our Kids – and How to Break the Trance. “Emotional connection,” he points out, “is built when eye contact is made. Our screens and screen culture have normalized the experience of having conversation with little or no eye contact. . . .Unfortunately, we are losing something vital and inherently human.”

If looking one another in the eye is inherent to our humanity, how are we doing on the human-connection front? Long before the glow-kid generation, we were coming up short on being present to one another. In Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, Emily Webb returns from beyond the grave to relive her twelfth birthday and marvels to see her mother once again, cooking breakfast and beginning the day. The Stage Manager warns her, “You not only live it, you see yourself living it.”

What Emily sees causes her to break down sobbing. She sees her mother hurrying through the morning routine, barely noticing her presence. Emily pleads, “Oh, Mama, just look at me one minute as though you really saw me. . . .Let’s look at one another.” She returns to her grave with the heart-shattering and eternal perspective that we, down here, often miss, “We don’t have time to look at one another.”

We are all thirsting to be seen. When we are seen, in our beauty, gifts, and goodness, by another person, it has life-giving power and often gives us the courage and confidence to fulfill a potential we did not see in ourselves.

The gaze of Christ had this power. Christ’s look at Peter after his threefold denial, “The Lord turned and looked straight at Peter” (Luke 22:61), filled Peter the Failure with compunction, and he went out of the Temple precinct and wept. But through that loving gaze, he became a better man, Peter the Rock, upon whom Christ built His Church.

Peter himself will become a healer. He looks with power, for example, upon the lame man: “Peter looked straight at him, as did John. Then Peter said, ‘Look at us. . . . In the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, walk.’” (Acts 3:4-6)

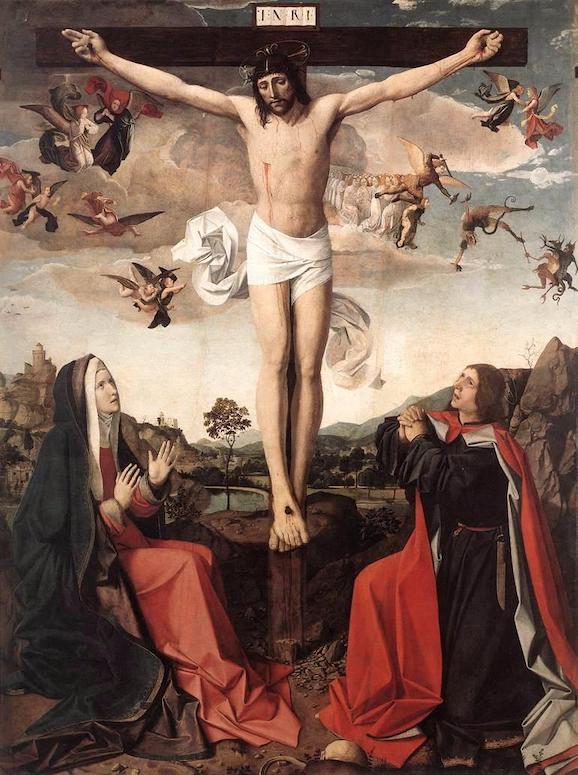

From the Cross, Christ entrusts mankind to His Mother’s gaze, proclaiming, “Woman, behold your son.” In turn, He entrusts her to our gaze, commanding us, “Behold your Mother.”

We are called by Christ, as His dying command, to know the living, life-giving power of beholding, of seeing the existence and the goodness of the person in front of us, recognizing it, receiving it, and responding to it worthily. He told us to take Mary into the home of our heart, and promised that she will take us into hers. St. John takes Mary into his home in Ephesus, and even more into his heart and life, becoming the person Our Lord has called him to be from all eternity.

Our Lady’s gaze always heals, restores, and reassures. In Her apparition at Guadalupe, she says to the humble Juan Diego, “Am I not here, I who am your Mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection?” Do I not see you?

A powerful aspect of the miraculous tilma of Guadalupe is the scientific evidence found within the eyes of Our Lady’s image. Examined with microscopic detail, they carry, emblazoned on the iris, a perfect replica of all who were present when Juan Diego unfolded the miraculous image.

Our Lady’s eyes saw them, and we see them in her eyes. They are known and they are loved. They are called by her gaze. The Virgin Mother continues to gaze into our eyes, even as we gaze into her eyes. Her gaze is filled with love from her heart perfectly united to the Heart of her Divine Son.

She calls us to fulfillment through her loving gaze. She tells us we are beautiful and irreplaceable, helping us to see the goodness she sees within us. Her gaze is her Son’s gift to us. And, in being seen through her eyes, we become fully and for the first time all she sees, all that she knows us to be.

Mother Teresa urged us to say to those we love, “I delight that you exist.” I see you, and what I see is good. You are important. Believe in the life-giving power you have to see someone into a more complete existence. Allow them to see themselves through your eyes.

“You know me, O Lord,” says the prophet Jeremiah, “You see me.” (Jeremiah 12:3)

Seeing seems so simple. Of course, we see. But when we know another through seeing, when we inspire, encourage, and call forth their hidden, unseen beauty, we give life through our gaze.

*Image: Calvary by Josse Lieferinxe, c. 1500 [Louvre, Paris]