If you were a medieval Jew in Colmar, a lovely town in the Alsace region of north-eastern France, you knew you might be attacked and robbed at any moment. You were an easy target, because you lived among your co-religionists in just one area of town – mostly on a single street, la rue des Juifs – and because you were devoted to your faith and its practices and dressed accordingly. You had nowhere to hide.

But you could hide your valuables, which is what one Jewish family did, creating what amounts to a safe deposit box: a terracotta pot containing their treasures placed in a hole in the wall of the house, then plastered over. However, some calamity caused them to leave their treasures, only to be discovered in 1863 right where they left them – nearly 400 years later.

As the catalog for “The Colmar Treasure: A Medieval Jewish Legacy,” a new show at New York’s Metropolitan Museum Cloisters, explains, the exhibit “revives the memory of a once-thriving Jewish community that was scapegoated and put to death when the Plague struck the region with devastating ferocity in 1348–49.”

The “discoverers” of the cache, which includes “silver coins, silver table ware, and gold and silver jewelry including elaborate belt buckles and fifteen silver rings,” probably used a finders-keepers ethos, selling some portion of what they uncovered. What has survived to be seen and loved by future generations is mostly at the Musée de Cluny in Paris, also known as the National Museum of the Middle Ages, which is a source, via loan to the MET, of several of the objects at the Cloisters.

The centerpiece of the small exhibit is a rather large wedding ring adorned with an imagined replica of the Temple of Solomon. Clearly, it was a ceremonial ring, which is to say you wouldn’t wear it doing work around the house but also that it was specifically intended to be worn only at a betrothal ceremony and/or the wedding itself. Indeed, some speculate that the ring was passed along over the generations within a family or even used by many – if not all – of the village’s Jewish brides on their wedding days.

The ring bears an inscription of the perennial Jewish expression of congratulations, “Mazel tov!” It’s actually a Yiddish phrase, not directly from Hebrew, although it’s written in Hebrew. It emerged in the 800s in Europe, an amalgam of Hebrew and Aramaic married to German and some Slavic languages. Yiddish, the word itself, comes from Yidish Taitsh, meaning “Jewish German.”

Although he wasn’t the last writer to write in Yiddish, the Nobel Laurate Isaac Bashevis Singer is certainly the most famous (and may be among the last) to write exclusively in Yiddish. He once said:

People ask me often, “Why do you write in a dying language?”. . .I like to write ghost stories, and nothing fits a ghost better than a dying language. The deader the language the more alive is the ghost. Ghosts love Yiddish and, as far as I know, they all speak it.

That’s a charming yet sadly fitting commentary on what you see at the Cloisters’ Colmar exhibit. Of course, the museum – like all museums – is filled with “ghosts.” Even the collection at New York’s Museum of Modern Art contains work mostly by artists now gone to the grave. (MoMA, after a long renovation, is about to reopen in October)

The ghosts seemed more painfully present to me at the Cloisters, since this small show seems emblematic of the history anti-Semitism: here is work by great artisans, members of a great culture, who very much by virtue of their courage and wisdom have been for millennia the scapegoats of the cowardly and foolish.

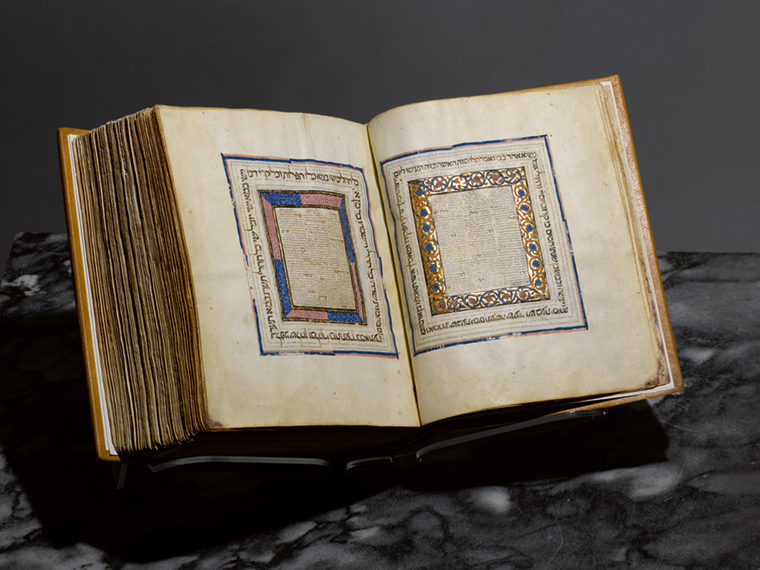

Also on display with the Colmar treasures are two items from the Cloisters’ permanent collection: a nearly 700-year-old Tanakh (or Hebrew Bible) and a Haggadah (of the same vintage), both from Spain. A Haggadah, for those who don’t know, is the text used at the Passover Seder, the remembrance of the beginning of the Exodus.

As curator Barbara Drake Boehm writes:

The survival of the Hebrew Bible verges on the miraculous. . . .Names and dates penned inside its pages suggest that it left Spain by 1492, when the Jewish population was expelled. The Bible and its successive owners voyaged eastward along the Mediterranean, landing next in Greece, later in Egypt, returning still later to the European mainland. Today, it is one of only three surviving embellished Hebrew Bibles from fourteenth-century Castile.

We consider it a particular honor that it should end its travels at The Met Cloisters, where the Hebrew Bible will transform our presentation – and our visitors’ understandings – of medieval manuscript illumination. All other books belonging to The Met Cloisters were created for Christian use (and three of them were made in Paris within a ninety-year period). This manuscript awakens us to the Jewish community that was a vibrant part of the culture of medieval Spain.

It may seem a stretch, but the Colmar show made me more excited about the forthcoming trip to Israel my wife and I are planning, where I long to see the place chosen by God for His Incarnation and the homeland of a suffering people who have put the suffering caused by persecution behind them.

I should add that the Cloisters, one of my favorite “haunts,” is museum that transports you back to a world in which Catholicism defined every aspect of life, for better and – as this small exhibit of Jewish artifacts can’t help remind us – sometimes for worse.

“The Colmar Treasure” exhibit is on display at the Cloisters through January 12, 2020.