Jacques Maritain was one of the most prolific and influential Catholic writers of the twentieth century. The author of more than sixty books – among them monumental works such as Integral Humanism, The Degrees of Knowledge, The Person and the Common Good, Art and Scholasticism, Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry, and Man and the State, all published by major American publishers, all of which sold thousands of copies. Maritain became one of the best-known intellectuals of his time.

Maritain was devoted to the thought of Thomas Aquinas but always with an eye to bringing Thomas’s insights into dialogue with the intellectual currents in modern philosophy, politics, and social thought (something Leo XIII had requested in his encyclical on Aquinas, Aeterni Patris). His influence on the thought of popes from John XXIII through Benedict XVI was immense. He was especially close as both friend and mentor to the future Pope Paul VI, who seriously contemplated making him a lay Cardinal.

Maritain was French ambassador to the Holy See from 1945 to 1948 and was influential in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He was mentored by Charles Péguy, studied with Henri Bergson, and converted to Catholicism through the influence of Léon Bloy. He corresponded regularly with Charles Journet, Étienne Gilson, Yves Simon, and Thomas Merton. He taught at Columbia University; the University of Chicago; the University of Notre Dame, where there is still a superb Jacques Maritain Center; and Princeton University. He was, in short, one of the most prominent, consequential Catholic figures of his age. (Robert Royal’s A Deeper Vision is a wide-ranging account of these and many other figures in that Catholic Renaissance.)

So why, when I type “Maritain” into my computer, does my spell checker repeatedly “correct” it to “martian”? Then again, given the current disregard of his thought, he might as well be a Martian.

But this is not really an article about Maritain per se or the ephemeral nature of reputations. Yes, history moves on, and new thinkers emerge. But Catholics are not supposed to forget their intellectual traditions, especially those that have been notably formative.

Catholic thinkers such as Maritain, Gilson, Josef Pieper, and others like them – men and women who asked big questions and wrote to a broad audience of educated non-specialists – were once favored by Catholic journals and publishers. This is for the most part no longer the case. Send an article based on the work of Maritain, Pieper, or Yves Simon to a journal today, even one at a Catholic university, and you will hear, “We prefer to appeal to a broader audience,” even though those men wrote for a broad audience. By “broader,” these editors mean “less Catholic.”

Send a journal an article on Machiavelli, Locke, or Hobbes, and you might have a chance. Send them something on Augustine, and you’ll have a much harder time. Granted, there are journals dedicated to the thought of Augustine, but those are for specialists, and to get published there, it is necessary to write in dialogue with the immense secondary literature, so you are mostly writing about that literature and not about Augustine.

Some years ago, the Catholic poet Dana Gioia wrote a widely commented upon article in First Things about the lack of prominent Catholic writers and poets today. Something many commentators failed to notice was the wholesale loss of middlebrow culture across the board in America since the 1960s. It used to be standard for Americans to know some of the poems of Robert Frost, T.S. Eliot, and A.E. Housman, not to mention a few by Wordsworth, Shakespeare, and Donne. No contemporary poet has anything like the same cultural position. Who even knows the name of a contemporary poet, let alone any of his or her poetry?

Once, every educated person knew Fanfare for the Common Man and Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copeland. Now, there isn’t a classical composer alive who the man in the street could name. Once, scholars like Reinhold Niebuhr made the cover of Time magazine. Now it is some Kardashian.

America’s cultural problems aside, why have Catholics abandoned Catholic culture? Must every journal managed by Catholics and every major Catholic university constantly ape their secular counterparts?

Some years ago, a major Catholic university got funding to open a center to support scholarship in the Catholic intellectual tradition. The first director, terrified of the “narrowness,” soon changed the mission to support scholarship in the “Abrahamic traditions.” When asked whether the center was interested in scholarship on the thought of Aquinas, Augustine, or the Church Fathers, the director demurred: “We would definitely not be interested in supporting that. Too narrow and sectarian.”

So, naturally, within a few years, the center closed because, to be frank, no one really cares enough about narrow, highly intellectualized scholarship in the “Abrahamic traditions” to support it, especially not people who take their Christian, Jewish, or Muslim faith seriously.

So here’s the uncomfortable truth. If Catholics want expressions of a serious Catholic culture steeped in the richness of the Catholic intellectual tradition, they are going to have to support them. I am not talking about second-rate pious movies and little spiritual tracts. I am talking about the kind of serious scholarship, literature, and art based on the richness of the Catholic tradition: beautiful churches (not modernist boxes), superb music and poetry (not minimalist drivel), and scholarship that is not afraid to be Catholic and address the profound questions of human meaning.

American higher culture has been in thrall to modernist art and architecture and secular fads in scholarship now for going on fifty years. And many Catholics have followed right along: tearing out beautiful art to white-wash their church walls; putting up their own modernist glass boxes: erecting their own sculptures with pointy edges; hanging abstract paintings of nothing; publishing scholarship meant to impress intellectuals not enlighten the faithful.

Isn’t it time for something new? How about allowing a fresh breeze of culture to blow through the Church? I have never been sure what the new evangelization is. But isn’t it about time for a new aggiornamento?

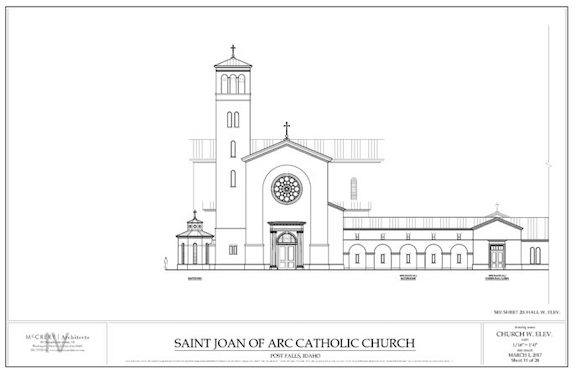

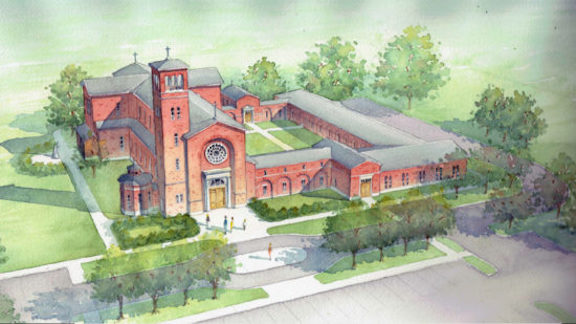

*Image: Old is new: Plans for St. Joan of Arc Church in Post Falls, Idaho