Newman 1, Amazonian Rationalizations 0

Robert Royal

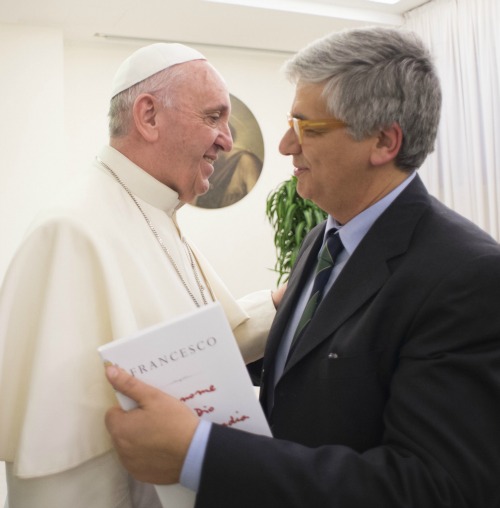

Andrea Tornielli is an intelligent man. He ran a rather good column series on Church matters at La Stampa, the main newspaper in Turin, for many years before he accepted a job in 2018 as editorial director in the Vatican’s Dicastery of Communications. He was offered that position, as was only to be expected, because he had become a fervent supporter of Pope Francis and had the journalistic skills to help out a communications office that was troubled, not least when Greg Burke, an American, and Paloma Garcia Ovejero, a Spaniard – director and vice-director of the Holy See Press Office – abruptly resigned after Tornielli’s appointment.

He and other public faces of the Vatican have had a tough assignment in recent weeks. Whether or not the figurines in the garden were Pachamama, and whatever you may make of the two men who took similar statuettes from the Carmelite church in Traspontina and threw them in the Tiber, none of this was exactly the best way for the Vatican to have made the case for the otherwise quite necessary inculturation of the Gospel in the Amazon region.

Anyone with an ounce of PR sense could have told whoever was responsible for the initial “tree-planting ceremony” that the “optics” – as we now say in the age of the non-stop media barrage – were very bad. And if anyone were to look at substance, it’s a slam-dunk mistake to allow such images to appear: It’s the job of the Church to bring Christ to the nations, not the gods of the nations to the Vatican.

We don’t know if anyone with such a minimal journalistic sense had an opportunity to speak to the relevant actors. Despite widespread suspicions by traditional Catholics that various plots are underway, much of what happens in the Vatican – especially this Vatican – is the result of disorder as much as of conscious decision and planning.

We do know that various spokesmen have had to result to pathetic dodges the past weeks. No one is willing to say what the figurines represented because, as I will not stop repeating, there are only two possible explanations:

- the figurines are regarded in the Vatican as trivial, like children playing with dolls, and the veneration the indigenous representatives showed toward them didn’t mean much of anything to our pope and bishops, despite all the talk of preserving indigenous “spiritualities.” This would absolve the pope from participating in an idolatrous pagan ritual, but at the cost of his giving the impression of taking indigenous ways seriously;

- or, the figurines are regarded in the Vatican as sacred. Indeed, some news outlets – the ever-entertaining National Catholic Reporter, America, and others who support Pope Francis uncritically – have described the casting of the images in the Tiber as a “desecration,” which can only happen if there’s something sacred to desecrate. This leads to an inconvenient truth, however, namely that a serious pagan ritual, involving pagan gods and goddesses, was permitted on the Vatican grounds.

There is no third here. And this is the logical problem into which the synod fell early because organizers didn’t think it was necessary to look, really, into “indigenous” elements that were being admitted.

So what does a spokesman do, besides trying to blur the issue so that a few news cycles will pass and the whole thing just slips away?

I’m sorry to have to say that he therefore lies – either intentionally or out of a sense that he needs to put up something plausible in defense – or if not that, grasps at straws by misrepresenting even so great a figure as St. John Henry Newman.

Someone clearly sent Tornielli a passage from Newman’s Apologia, which refers to the ways that the Church historically adapted pagan symbols to Christian purposes. That’s fine, so far as it goes, and no more than he truth. But the passage in question does not say – Newman was a serious Christian and not a spin-doctor – that the Church thought the pagan elements should be honored and the “spiritualities” behind them were thus to be “preserved.”

And besides, it was not a matter of pagan gods and goddesses being so absorbed, but peripheral symbols being repurposed. To put this in concrete terms, if only the native boat, paddles, fishing nets, and similar items had been present in the Vatican and nearby churches, who would have been disturbed?

But as you edge closer to real beliefs about real gods and goddesses, either the alarm goes off, or you’ve accepted that a sentimental affirmation of the Other, so common in democratic politics these days, has replaced the dire warnings from the earliest and most authoritative Jewish Scriptures about “strange gods.”

[Professor Eduardo Echeverria explains all this in theological terms in the separate column appended to this one below.]

In that light, the bishops who assembled in the Catacombs of Domitilla last week, to reswear to the preserving of Amazon spiritualities – a gesture liberation theologians made in the 1960s during Vatican II – is breathtaking in its disconnect from Catholicity – and in its self-righteous belief in its Christian liberality.

I have no doubt that there’s much worth preserving in indigenous ways that would not involve idolatry or the sacrifice of clear thought. But even granting that, one thing seems crystal clear to me: that some of the most influential figures in the Amazon Synod are not in a very good position to lecture the world about inculturation, least of all how it should now be carried out.

Robert Royal is Editor-in-Chief of The Catholic Thing

“Spoils from Egypt”

Eduardo Echeverria

As Robert Royal has outlined above, Andrea Tornielli, the editorial director of the Vatican Dicastery for Communication, has defended the legitimacy of using, in several ceremonies in Rome, the Amazonian wooden statues depicting a young pregnant woman as “an image of motherhood and the sacredness of life, a traditional symbol for indigenous peoples representing the bond with ‘mother earth’.”

Tornielli ignores the confusion that has followed. Does she represent the Virgin Mary or “Our Lady of the Amazon”? Fr. Giacomo Costa, a communications official for the Amazon synod, already ruled that out. Is she a religious symbol of the goddess Pachamama, or Mother Earth? Nobody at the Amazon synod seems to know.

Suppose we grant Tornielli the point he seems to be making, namely, that this image represents the “goods” of motherhood, life’s sacredness, and a bond with the earth. Can we treat these as “neutral goods” abstracted from the understanding of the indigenous peoples: an image of fertility and life expressive of a pagan and nature-centered religiosity? Once we reinsert these alleged “goods” – life, fertility, and mother earth – into the context of their religious worldview, it is clear that they are not conformable to the fullness of God’s truth in Jesus Christ.

Tornielli suggests that we can treat these alleged “goods” apart from their religious worldview. He even enlists St. John Henry Newman’s reflections in An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, Chapter VIII §2.6, suggesting that Newman legitimizes “the adoption of pagan elements by the Church.”

Newman wrote:

The use of temples, and these dedicated to particular saints, and ornamented on occasions with branches of trees, incense, lamps and candles; votive offerings on recovery from illness; holy water, asylums; holy days and seasons, use of calendars, processions, blessings on the fields, sacerdotal vestments, the tonsure, the ring in marriage, turning to the east, images at a later date, perhaps the ecclesiastical chant, and the Kyrie Eleison, are all of pagan origin, and sanctified by their adoption into the church. (emphasis added)

Yes, Newman does say this, but Tornielli leaves unexplained not only Newman’s understanding of the sanctification of these alleged “goods,” but also the entire context of this chapter where Newman discusses the “assimilative power of Dogmatic Truth.” Thus, Tornielli fails to make his point.

The “spoils from Egypt” trope is the context of Newman’s reflections regarding the sanctification of these assimilated goods. Newman’s main point – and it is a point lost upon this synod and, yes, on Tornielli – is this: the traditional spoils from Egypt trope insists that the “goods” from other cultures once assimilated must be purified, transmuted, fulfilling and perfecting them by the fullness of God’s truth in Jesus Christ. “[T]he grace in the Gospel. . . changes the quality of doctrines, opinions, usages, actions. . .when incorporated with it, and makes them right and acceptable to its Divine Author, whereas before they were either infected with evil, or at best but shadows of the truth.” (VIII.§2.5)

Newman is not alone in making use of the “spoils from Egypt” trope. St. Augustine explains this in On Christian Doctrine, Bk 2.XL.60:

Like the treasures of the ancient Egyptians, who possessed not only idols and heavy burdens, which the people of Israel hated and shunned, but also vessels and ornaments of silver and gold, and clothes, which on leaving Egypt the people of Israel, in order to make better use of them, surreptitiously claimed for themselves. [Exod 3:21-2, 12: 36-6] – similarly all the branches of pagan learning contains not only false and superstitious fantasies and burdensome studies that involve unnecessary effort, which each one of us must loathe and avoid as under Christ’s guidance we abandon the company of pagans, but also studies for liberated minds which are more appropriate to the service of the truth. . . .These treasures – like the silver and gold, which they did not create but dug, as it were from the mines of providence, which is everywhere – which were used wickedly and harmfully in the service of demons must be removed by Christians. . .and applied to their true function, that of preaching the gospel.

The general principle behind St. Augustine’s reflections is that we may discover truth and goodness in pagan religions and philosophical systems, but we must consider that the interpretation of these truths and goods is often such that they distort and misinterpret them from the perspective of their religions and systems.

Thus, these truths and goods need to be broken open and freed from their perspective in the direction of Christ by a “clarifying transposition,” which involves cleansing these fragments, polishing them “until that radiance shines forth which shows that [they are] fragment[s] of the total glorification of God.” (Hans Urs von Balthasar)

This, too, is the view of Vatican II. No wonder Ad Gentes §9 takes the Church’s missionary activity to involve a “purg[ing] of evil associations [of] every element of truth and grace which is found among peoples.” Or that Lumen Gentium, §16-17 speak of “deceptions by the Evil One” at work in a man’s resistance to God’s prevenient grace as well as that the gospel “snatches them [non-Christians] from the slavery of error and of idols” and the “confusion of the devil.”

Indeed, Ad Gentes §9 speaks of the fragments of truth and grace to be found among the nations that the gospel “frees from all taint of evil and restores [the truth] to Christ its maker, who overthrows the devil’s domain and wards off the manifold malice of vice.”

The Catholic Church is deeply committed to the “all-embracing authority of Christ” (cf. Matt 28:18) over all forms of creaturely truth because in Christ are hid all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge. (cf. Col 2: 2-3) Hence, Christians cannot rest until they have taken every thought and practice that has been raised against the knowledge of God into the service of the Lordship of Christ. (2 Cor 10:5)

Eduardo J. Echeverria is Professor of Philosophy and Systematic Theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Detroit.