In my historical imagination, the line that marks the English Reformation slices right through Saint Thomas More’s neck.

He wasn’t merely defending the Catholic doctrine on marriage, against a willful king who found it inconvenient. He had a clear view of circumstances far beyond this.

Light and witty as he could be, and a magnificent controversialist, he didn’t lay down his life in order to clinch a debating point.

In his bowels, he realized that the whole order of Catholic Christendom was at stake. Moreover, he was in a reasonable position to foresee what would happen. For on several fronts (Luther articulating only one) that order was under attack.

That he could not foresee exactly the sequence of events that would follow upon his own martyrdom goes without saying. No man can do this, and prophecy does not require it.

More was a controversialist. His English works were massive, more than 1,000 closely printed pages. (His misunderstood humanist potboiler, Utopia, was among his Latin works.)

The modern reader cannot cope with them. What was controversial five centuries ago is not in the news anymore, and English itself is in style and vocabulary somewhat “evolved.”

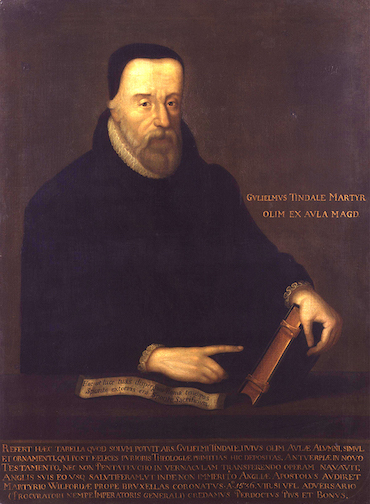

We would not dream of following the argument between More and Tyndale, for instance, on the latter’s translation of the New Testament.

But if we did, we would find not only rough rhetoric but a patient defense of Catholic tradition, including Biblical interpretation, that hasn’t gone out of date.

We would also find shocking things that More is saying, that we can misunderstand by anachronism. For in addition to reading, we must reconstruct the context in which he wrote – a world unlike that of today, and a Church that has not experienced five centuries of novelties.

An example, in his Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, he easily accepts the idea that the liturgy could be presented in English, he cites I Corinthians 14 to explain it.

Yes, it would be “a language understanded by the people,” but not follow stripped down. We, owing to developments since Vatican II, now take it for granted that the language should be fully colloquial.

The idea that what is sacred should be presented in a language that is sacred, taken for granted then, isn’t now. Indeed, with Tyndale, the fight over that was just beginning.

We have just passed the tenth anniversary of Anglicanorum Coetibus. This apostolic constitution of Pope Benedict XVI’s was celebrated here in Toronto with a conference in which I participated.

Among other excitements, this noble attempt to retrieve the Catholic-leaning within the Anglican communion allows us to revisit the English Reformation. Our generation and any following have the challenge of gardening: of revising complexly beautiful Anglican texts by weeding out non-Catholic accretions.

Such efforts take time and require divine guidance. Like the Englishman More, we must realize that the history of his Church in the English-speaking realm goes back many centuries, and that English was just one of its tongues.

The old Sarum Rite is part of our Roman (and Norman) heritage; we pass back through Angles and Saxons, even Danes, into a misty Goidelic realm; to the first emissaries from Rome – and Egypt. An “English Church” must encompass all this.

But it’s part of the Church, not the history of a nation. It’s a spiritual, and not a political fact.

I personally “jumped the gun” on Pope Benedict’s magnificent constitution. I crossed the Tiber well before, in a state of mind so inimical to the Anglican church (as it had become), that I became an immediate Latin Mass aficionado.

Thomas More’s acknowledgment of the possibility of the Mass in English surprised me. Did he know what that could lead to?

But degeneration is possible in any language; and conversely, the sacred can be assimilated within all. While Latin must, through any foreseeable future, remain the “lingua franca” for the universal Church, she must also accommodate a “pentecostal” world that often resists Latin.

The significance of the Anglican liturgical tradition cannot be detached from Protestant history; herein lies the danger. The beauty of it cannot be overlooked, either. Generations of Anglicans trying to be true to the traditions of the Western Catholic Church were its authors.

Moreover, it coalesced at a time when this living tradition was still within touch, and when the English language was at its greatest.

Not only “great” in “the language of Shakespeare” sense, but too, as a practical matter. Those who have studied will realize that it’s much easier to translate the classics as well as the Bible into Elizabethan and Jacobean English WITHOUT modern idiom and cliché.

Moreover, as with Shakespeare, a minimally intelligent modern reader will get used to it quite quickly. A few word changes and an occasional footnote will clear any misunderstanding. His spoken language will also be improved in the course of adjusting.

As More did not doubt (even before English prose style had fully matured within its modern structure), we had the facilities to do a worthy translation. Until quite recently, the usages of the King James Version and the Book of Common Prayer had kept this alive.

And now they are again ours, as it were, as if someone had returned our silverware. We have finally retrieved what was Catholic within the English-speaking Protestant realm, at a time when English has become a kind of lingua franca even within ancestrally Catholic realms.

English-speaking Catholics (in America and around the world) are, and will be, in the vanguard of the recovery of Catholic faith and morals, so far as I can see. The time for a worthy English version of the Mass has arrived, by several unexpected channels.

But it will be a disaster if the Catholic faith does not resume its place at the heart of this development.

For the purpose of it is to save men, not a certain language and tradition. It’s too late to revive More’s corpse; but never too late to revive the cause he served, even among those who betrayed it.

*Image: Sir Thomas More by Hans Holbein, the Younger, 1527 [Frick Collection, New York]

**Image: William Tyndale by an unknown artist, c. 1540 [National Portrait Gallery, London]