It’s fair to say that no Christmas story except THE Christmas story (the one St. Luke relates) has had more enduring popularity than Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. In the brief survey below of dramatic adaptations, I’m going to focus solely on films (excluding all TV and animated versions – and ones with puppets), despite the fact that fine actors such as George C. Scott, Michael Caine, Albert Finney, and Patrick Stewart have participated in some of them.

The very first dramatic presentation of A Christmas Carol was by Dickens himself, who read the book to enthusiastic audiences in Birmingham, England in 1853, a decade after the book’s publication. Since then there have been more than sixty theatrical productions (in an uncountable number of performances, including revivals), several dozen cinematic versions, and nearly three-dozen TV or direct-to-video versions. I’m not going to attempt to tally up all the radio performances and recorded books. There have been four operas. And you probably couldn’t count the number of TV series that have had episodes with a haunted-villain-changes-his-life storyline.

Mr. Dickens was not a Catholic (in fact, he called our faith “a curse upon the world”), and he was not a particularly enthusiastic Anglican either. But he did have a sense of how faith can transform lives, and it’s reasonable to say that, in A Christmas Carol, Ebenezer Scrooge has a born-again experience (well, better to call it metanoia) thanks to the visits of the three ghosts. It’s also obvious from much of his work that Dickens was a proponent of the Social Gospel; that he saw Christianity as a force for justice, especially justice for the poor.

Three years after A Christmas Carol, he wrote a book called The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, which he insisted never be published (he intended it only for his own children), a request his family honored until 1934 – sixty-four years after the author’s death (and earning the heirs the 2019 equivalent of $4 million). It is, I believe, the only of Dickens’ books that remains under copyright protection (all the rest are in the public domain), which is why there are hundreds of different editions of A Christmas Carol available in print and online. Sad to say, his life of Christ is dramatically lifeless and theologically inept. He seems in awe of a very small God – if his Jesus is God. The book scans to me almost an example of docetism.

Meanwhile, I assume every reader of The Catholic Thing knows the story of Ebenezer Scrooge. As Dickens so vividly describes him:

a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days; and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.

Our icy hero! Yet a thaw does come. The transformation of Scrooge from a despised, covetous sinner into a joyful, loving patron is a movie actor’s dream – a sensational “character arc,” which is key in all of fiction: a character who ends up where he started isn’t much of a character. Anybody who has ever played Scrooge has needed to figure out how to go from sour to sweet, and three have done it brilliantly (all, unsurprisingly, Brits).

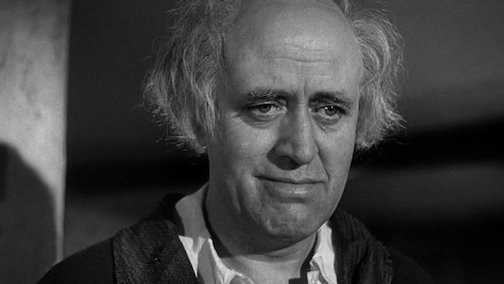

I am partial, barely, to the 1951 British version starring Alistair Sim, although I’m also very fond of the 1938 American version starring Reginald Owen. But there is also Scrooge (1935) starring Seymour Hicks, which was a remake of a 1913 version – same title, same actor. Hicks (1871-1949) is forgotten now, but he was a major stage star, who successfully made the move into film. Mr. Hicks may have been the prototype that Sim and Owen looked to. (Click on the names of the actors below to watch each film online.)

You will be moved at the end of Mr. Hicks’ version when Scrooge enters a church as the people sing “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.” (A free colorized version is available via Amazon Prime. I don’t usually care for colorization, but this works well, rendering the film in images reminiscent of antique Christmas cards.)

The transformation of Mr. Owen’s Scrooge is subtle, but remarkably charming, especially so when he shows up to bestow gifts upon the stunned Cratchit family. Interesting casting in that Bob Cratchit, Mrs. Cratchit, and daughter Belinda are played, respectively, by the Lockhart family: Gene, Kathleen, and June. This was June’s debut, and people of a certain age will remember her from TV’s Lassie and Lost in Space. The scene ends, of course, with Tiny Tim’s beautiful toast, “God bless us every one!”

But, as I say, for me the best is Mr. Sim’s, in a version that’s actually also called Scrooge, although it’s sometimes marketed under Dickens’ original title. When Sim’s Scrooge confronts Bob Cratchit, who has come in late to work on December 26, and surprises his clerk – who expects to be fired on the spot – by raising his salary, Mr. Sim laughs – a kind of astonished, rolling chuckle, because he is still in the throes of self-rediscovery. Wiping his eyes, he says, “I don’t deserve to be so happy.” Who does?

Dickens writes of old Ebenezer that:

Some people laughed to see the alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter in the outset. . . His own heart laughed: and that was quite enough for him.

The merriest of Christmases to all readers of The Catholic Thing!