A few months ago I had the good pleasure of participating in a conference held at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. The conference was quite stimulating, as one would expect; but the special grace was to join the Dominican students and faculty in celebrating the liturgy in their lovely and venerable chapel. The Liturgy of the Hours was celebrated reverently with chant and silence. And even the body language of the participants bespoke wonder before the Word of God.

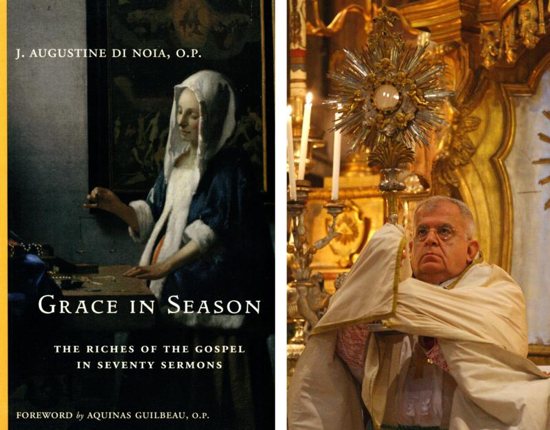

In that very chapel, the noted Dominican theologian, Archbishop J. Augustine Di Noia, preached many of the homilies now happily collected in the attractive book, Grace in Season: The Riches of the Gospel in Seventy Sermons.

“Seventy,” of course, is a Biblically charged number, signifying fullness. And there is a fullness in this collection, spanning the major liturgical seasons, special feast days, and specific occasions, ranging from the celebration of the ordinations of Dominican confreres to the funeral homilies for the preacher’s beloved mother and sister.

Whatever the occasion of the sermons, one is struck by their “objectivity.” By this I do not mean they are “impersonal” – far from it! But they receive their orientation from the objective realities presented by the liturgical celebration, its particular readings, prayers, and hymns.

Hence, the sermons are personal, even conversational, but not subjective. The hearers and readers are not regaled by anecdotes, experiences, idiosyncratic views. We are confronted by the Good News of Jesus Christ and his Grace, which is ever free, but never cheap. Di Noia’s “conversational” preaching subserves a conversatio, a call to conversion and transformation in every season.

Besides these sermons’ evident orientation toward the realities the liturgy celebrates, they are also characterized by an “integrity.” They are not “stand alones,” but deeply integrated into the liturgical action. This appears not only in their exposition of the specific scriptural readings, but also by their frequent reference to the prayers of the particular Mass being celebrated.

I think preachers too often neglect the richness and challenge of the collect, the prayer over the gifts, and the prayer after Communion. Invoking them in the sermon can provide a prayerful dimension to the sermon itself, reinforce what the congregation had already heard, or, in too many cases, supply what their late arrival at Mass had made them miss. In his sermons, Di Noia frequently alludes to the prayers as well as the readings. And to the hymns!

The nineteenth-century Protestant theologian and preacher, Friedrich Schleiermacher once opined: “before the sermon there is the hymn.” Di Noia’s Italianate sensibility takes the injunction to heart. The hymn itself, if substantive (as the hymns sung at the Dominican House of Studies are!), is a mini-homily – one all the more effective in that it touches both mind and heart. Hence, often enough, Di Noia will invoke the hymn that has been sung, citing verses to underscore points he seeks to make.

Once more the impression created is that the liturgical celebration is an integral whole, each of its components making an indispensable contribution toward the one end: the praise and glory of God. As an obiter dictum let me add that if the hymn is a theologically substantive one, all the verses should be sung. To cut it short before the concluding doxology is nothing less than a liturgical mutilation.

Thus the sermons collected in this volume manifest a fine medley of the liturgical, the theological, and the aesthetic, each dimension complementing and enhancing the other. It is fitting (a Thomist would undoubtedly say “congruent”), therefore, that the paperback volume is attractively formatted, easily legible, and includes a helpful glossary of the sermons’ date and place of delivery, as well as identifications of the citations given in the sermons.

And, though the caution not to judge a book by its cover is usually wise, the cover of this book is both inviting and distinctive. It depicts Vermeer’s splendid painting, “Woman Holding a Balance.” Aside from the fine detail that characterizes all of Vermeer’s work and the subtle interplay of light and shadow, one can discern a further dimension.

Prominent among the jewelry that appears in the foreground of the painting is a string of pearls. And in the background, behind the woman intent on her scales, is a large painting of the Last Judgment, with Christ the Judge, bathed in a nimbus of light, presiding over the scene.

The scene seems to portray a woman’s calm appreciation and assessment that earthly goods must be weighed in light of heavenly judgment.

Whatever Vermeer’s own intent, the use of his image to lead us into these excellent sermons serves an almost mystagogic function. What is the pearl of great price that we seek? And what cost are we willing to bear? The sermons tell us, in T. S. Eliot’s words, that “the cost is not less than everything” – and that eternity is in the balance.