Franz Jägerstätter was an Austrian farmer who refused to pledge allegiance to Adolf Hitler and was guillotined by the Nazis on August 9, 1943. He was beatified as a martyr by Benedict XVI in 2007.

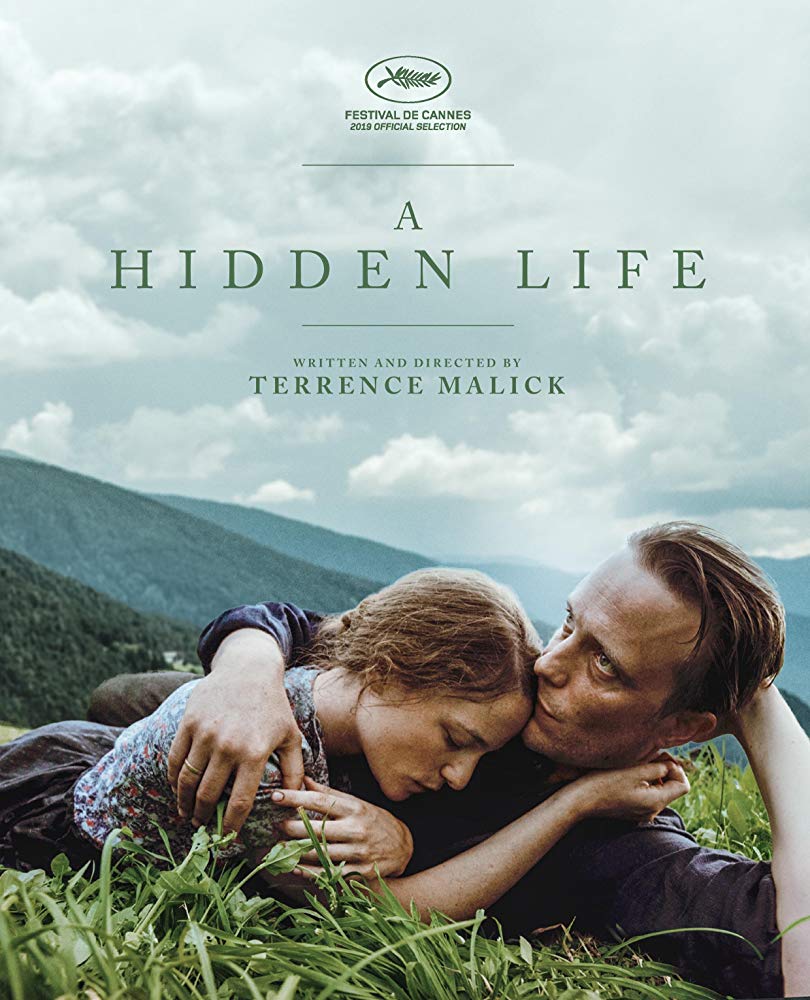

His life is worthy of a major motion picture, and I was genuinely excited to see A Hidden Life, Terrence Malick’s new biopic about Bl. Jägerstätter. If you’ve never seen Mr. Malick’s 1978 film, Days of Heaven, you should, and you’ll be impressed by the look of it, although much of the credit for that belongs to Nestor Almendros, one of the finest cinematographers of the last century. In any case, Malick’s films have ever since been notable for their visual beauty.

But, Mr. Malick, although something of a visionary, is not a particularly accomplished entertainer, a consequence of which is that his films lack the humanity that arises from vivid characterization and language, and this is especially true of A Hidden Life, which has very long sequences in which the film’s characters say nothing or next to nothing and don’t do much either. It’s rather like a perfume commercial.

Jörg Widmer’s camera work on A Hidden Life is very good, if somewhat static. It’s like sitting in a medical office, waiting between the nurse’s visit and the doctor’s arrival, and staring at an HDTV screen as one high-definition photo after another cycles through: mountains and rivers and lakes. In A Hidden Life, it’s the scenery of Italy’s Tyrolean Alps (standing in for Austrian mountains), but scenery it is, interrupted only now and then by human faces, usually shot in tight to show human feeling: joy or sorrow, apparently the only emotions there are. Sometimes these humans talk to one another, although much of the narrative is accomplished in epistolary fashion: letters between Franz (August Diehl) and his wife Franziska (Valerie Pachner).

One peculiar aspect of the film is that when these Austrians do speak it’s usually in English, whereas the Germans mostly speak German (without subtitles), although when German characters speak calmly to Jägerstätter, they also do so in English, but never when they’re angry – as they usually are.

Jägerstätter and his family are ostracized (a prophet never being welcome at home), and when they’re cursed by the villagers in Sankt Radegund – where Jägerstätter was born, raised, married, and lived until he was arrested for his conscientious objection – those expletives also flow forth auf deutsch.

Sadness adds to sadness, because Franz had been a favorite son of the village, back before the Anschluss – when Sankt Radegund remained a community “alone in the clouds.”

Part of Jägerstätter’s story that Mr. Malick doesn’t tell is his wife’s influence on Franz’ faith. Together – in real life, that is – they made a pilgrimage to Rome and began serious Bible study. He became a Third Order Franciscan and was a sacristan at the local Catholic church. The closest Malick gets to any of this is in scenes in which Franz sweeps the church’s apse or pulls a rope to ring its bell. And there’s one lovely scene (not involving Franz) of a procession through the countryside, concurrent to confirmations from which the Jägerstätter children are excluded.

Yet it’s unclear in the film whether Jägerstätter’s refusal to participate in Hitler’s war derives from his religion or his politics. He speaks to the local priest and then to a bishop, both of whom are mildly sympathetic but urge him to serve in the army – for the sake of his wife, his three daughters, his community, and his fatherland. Their arguments are very much like those many made to St. Thomas More: Just sign the oath; God will know what’s really in your heart.

As with those scrolling doctor’s office images, Malick uses many, many cuts: from here to there; forward and backward in time. Three editors are listed in the film’s credits. It is wearying to watch, because, through the many scene changes, so little actually happens, and, especially, because the film is nearly three-hours long: 174 minutes to be exact.

I have to say, and with all due respect to a good filmmaker who shoots beautiful movies, it is ridiculously long. The arguments about why he should say “Heil, Hitler!” are made to Franz not once or twice but half-a-dozen times. Work around the Jägerstätter farmstead is shown over and over, as are walks to and from the village, as are tense confrontations with villagers – so much of all of it shot in silence.

When I got home from the screening, my wife asked, “How was the film?” I said: “Interminable.”

It’s hard to understand artistically, and the only explanation I can come up with is that Terrence Malick is not a generous filmmaker, by which I mean he indulges himself without concern for his audience.

The film has been taken by many to be Catholic in its sensibilities. Perhaps. But I’m not sure Mr. Malick isn’t, in fact, “doing Bergman,” by which I mean rebooting Ingmar Bergman’s “silence of God” meme. Indeed, A Hidden Life seems less a testament of faith than a plea for apostasy in the manner of Martin Scorsese’s Silence (2016). As I wrote in my review of that film, “apostasy becomes an act of Christian charity when it saves lives, just as martyrdom becomes almost satanic when it increases persecution.”

Malick’s next project, The Last Planet, is about Jesus Christ. One person involved in that film has called it a “highly spiritual experience” with a “dark genre twist” on the Bible. Based on A Hidden Life, we may hope “dark” and “genre twist” don’t indicate a film along the lines of Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. We’ll see.

____

A Hidden Life is rated PG-13 for violence in scenes depicting the Nazis’ torture of Bl. Jägerstätter.