Why Do Christians Believe in Hell? Because Christendom has affirmed it, Jesus clearly teaches the reality of Hell in the Bible, and Hell’s reality resonates with an honest account of our own experience.

That’s not the answer theologian David Bentley Hart gave earlier this month, when the New York Times offered him a perch to discuss the misguided beliefs of his fellow Christians. The Bible is so unclear about Hell, he wrote, while it is clear about universal salvation, that the doctrine of Hell must be purely an expression of the ill will of Christians. They hate their fellow human beings so much that they want them to spend eternity in torment.

When the Roman Empire embraced Christianity, Hart writes, the doctrine of Hell was a form of “spiritual terror,” which served as an “indispensable instrument of social stability.” But the enduring motives, Hart insists, have always been deeply personal – and demented. Christians derive a “secret pleasure,” he says, from hoping that, when they are saved, they will be envied by the damned: “What heaven can there be. . .without an eternity in which to relish the impotent envy of those outside its walls?”

Indeed, the malice of these Christians knows no bounds, according to Hart. They cannot accept any “concept of God that gives inadequate license to the cruelty of which [their] own imaginations are capable. . . .The idea of Hell is the treasury of their most secret, most cherished hopes.”

That’s a pretty gross slander of Christians, which naturally the New York Times is eager to promote. Hasn’t it always been clear that those “enemies of the human race,” who oppose abortion, same-sex marriage, and other good things, harbor hatred within their hearts? Now even one of their own comes clean about that! And if you want to become fully convinced of the inveterate malice of Christians in this matter, you can follow the link, which Hart kindly provides, to his new book about it.

Of course, a theologian like Hart who accuses billions of Christians of malice, and who opines that Christians take a morbid delight in setting themselves above others, puts himself in a rather exposed position. Didn’t Jesus say something about splinters and logs? So Hart has to package his attack as self-defense. His book, he says, has provoked a frenzy of criticisms (“if only,” you might say), which he variously describes as indignant, hysterical, truculent, uninhibited, and demented. He’s forced to account for these attacks against him, in the pages of the New York Times.

If someone were to ask me why Christians believe in Hell, my starting point wouldn’t be angry emails to Hart about his new book, but the Catena Aurea, on Matthew 25:46, “And these shall go away into everlasting punishment: but the righteous into life everlasting.”

The Catena Aurea, or “golden chain,” is St. Thomas Aquinas’ remarkable stitching together of commentaries by the Fathers on the Gospels, to produce a single running commentary. It provides a balanced view of authoritative teaching by the Fathers on Scripture. I would start with Mt. 25:46, because that is a proof text for the existence Hell: if anything ever counts as a proof-text, it must be those words from one of Jesus’ own parables.

There’s symmetry here between the fate of the righteous and the unrighteous. The righteous are said to “inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.” (v. 34) But to inherit something is to be given it as one’s own possession, and the phrase “foundation of the world” points to an ultimate, not a conditional, reality. The unrighteous similarly are consigned to “everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels,” which must, therefore, be as fixed and unalterable as is Satan’s will against God.

The word rendered “everlasting” here (aiōnios, which draws upon the meaning of “endlessness” inherent in its Indo-European root, *aiw-, just like our word, “ever”) is always used in that sense in the New Testament, mainly for “everlasting life.”

But more importantly, Jesus uses the same term for the duration of the punishment, as for the duration of the life. What holds for the one, then, must hold for the other. If the life is everlasting, the punishment is everlasting.

The term for punishment, too, has connotations of torment, as indeed the word “fire” suggests. “Some deceive themselves,” St. Augustine says, quoted in the Catena, “that the fire indeed is called everlasting, but not the punishment. This the Lord foreseeing, sums up His sentence in these words.”

Hart bites the bullet. To make the everlastingness of Hell look doubtful, he makes that of Heaven doubtful. Here’s how he renders Mt 25:46 in his recent translation of the New Testament: “And these will go to the chastening of the Age, but the just to the life of that Age.”

What? “The frightening language used by Jesus in the Gospels,” Hart assures us in his New York Times column, “when read in the original Greek, fails to deliver the infernal dogmas we casually assume to be there.” At least, his translation makes sure that it fails to deliver. But, similarly, it fails to deliver the dogma of Heaven. Every promise Jesus makes about eternal life becomes, in Hart’s rendering, a promise about “life in the Age.”

But Hell is not simply a truth that Jesus teaches and indirectly affirms on many occasions (e.g., as when he says that it would have been better for his betrayer not to be born, Mt 26:24). As the Fathers point out, it resonates in our hearts, not because it is “there” already, but because we are aware that we have freedom to reject God and the good. And we sense that chances eventually come to an end. We can set ourselves on evil, and a true attitude of penance recognizes no claim on God to bail us out. (Ps. 51:4)

Hart and other recent writers make strenuous efforts to deny the truth, but the words stand.

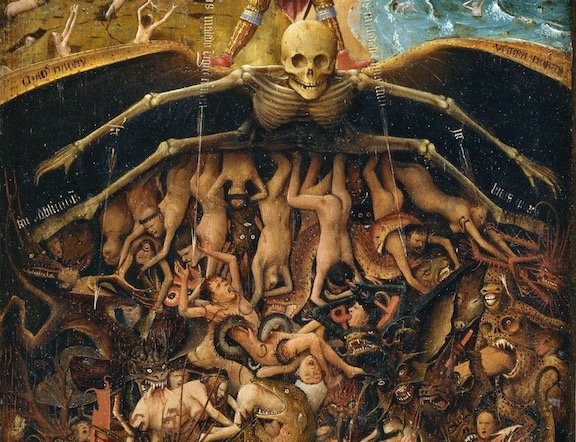

*Image: The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck (detail), c. 1440-41 [The MET, New York]. This is the bottom area of the right panel of a diptych.