Consider the curious but instructive story of Jonah. We all know that he fled from God’s call and ended up in the belly of a whale. But then there’s the lesser-known part of the story: Jonah’s second chance, when he actually did go to prophesy in Nineveh. Hearing him proclaim their impending doom – Forty days more and Nineveh shall be destroyed! (Jon 3:4) The Ninevites repented, cried out for mercy, and were spared.

Which should have delighted Jonah. Despite a rocky start, he proved himself an effective prophet. But instead, this greatly displeased Jonah, and he became angry. (Jon 4:1) Why? Because the Ninevites were Israel’s enemies. Nineveh was the seat of the Assyrian empire and its survival meant continued oppression for little Israel. Jonah – like all Israelites – wanted Nineveh destroyed, not spared. So in the last chapter of the book, we find him pouting, I knew that you are a gracious and merciful God, slow to anger, abounding in kindness, repenting of punishment. (Jon 4:2)

Jonah witnesses ironically to God’s mercy, by way of resentment not joy. The whole moral of the book is that the prophet must share and interiorize God’s merciful will. However much Jonah wills the destruction of the Ninevites, God desires their salvation. And for the prophet to have any authenticity, he must share the desire of the One Whose word he speaks. Of course, in Jonah’s defense, he understood all this. . .which is why he ran away in the first place.

The lesson of Jonah comes to mind as we hear our Lord’s sobering words: Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you. (Mt 5:44) There is more than a little Jonah in each of us. We know Jesus’ command. We acknowledge and salute it from afar. Indeed, we graciously admit its noble sentiment. But we are like Jonah in our flight from its demands.

Our flight takes the form of keeping His command of forgiveness at arm’s length – for example, when we say things like, Certainly, I’ll forgive my enemy. . .when he asks for forgiveness. In fact, we should choose to forgive our enemy before he shows any sign of repentance – and whether or not he ever does. Note that in the Gospels our Lord extends forgiveness without anyone asking explicitly for it or, in some cases, even expecting it (e.g. the paralytic in Mk 2).

Or we flee the demand by trivializing the need for forgiveness. We shrug off wrong-doing (Don’t worry about it. . . .No worries. . . .It’s all goooood) and move on. Our culture’s preferred method of flight is to reduce Christ’s command of love to mere tolerance. As if He had commanded us to tolerate our enemies or said, Tolerate one another as I have tolerated you. Indeed, the current fascination with tolerance (especially among doctrine-averse Catholics) is a Jonah-like way of fleeing the Gospel’s demands.

To stop fleeing means to will and to desire earnestly what is good for our enemies as Christ Himself does; to will what brings them holiness in this world and salvation in the next. Looking upon His enemies from the Cross, even as they crucified Him, Christ desired that they be with Him. Neither awaiting their repentance nor downplaying their wickedness, He prayed, Father, forgive them, they know not what they do. (Lk 23:34)

In a sense, we can’t help but flee. Our fallen human nature on its own is unequal to such forgiveness. We are too selfish, too frightened of the cost. And here we realize the need for interior regeneration before we can obey His command. We cannot unite our weak, selfish will to His generous mercy unless His grace moves us.

As the Catechism observes, It is impossible to keep the Lord’s commandment by imitating the divine model from outside; there has to be a vital participation, coming from the depths of the heart, in the holiness and the mercy and the love of our God. (§2842).

This vital participation – really, our divine filiation – requires us as God’s children to share His love for our enemies. Jesus explicitly connects mercy with sonship: That you may be children of your heavenly Father. But divine filiation requires still more: namely, that we be so united with our heavenly Father that we desire for our enemies and persecutors what He desires.

Unfortunately, our prayers for our enemies tend to be really about ourselves: Dear God, make them the way I think they should be. . . .Dear Lord, make them stop annoying me. . . .Almighty Father, tell them to be quiet. Of course, to love our enemies and pray for our persecutors as children of God means to desire that they become what God wills them to be, not what we think they should be. It means to participate in God’s will for their good.

Most importantly, it is His grace – that vital participation – that moves our wills to this forgiveness. He gives an extraordinary command because He gives the grace to respond. Saint Augustine’s prayer applies here: Da quod iubes, Domine, et iube quod vis – Give what you command, and command what you will. Our Lord can command the seeming absurdity of loving our enemies and praying for our persecutors precisely because He has – already – given us the grace to do so.

Jonah made ready to flee. . .away from the Lord. (Jon 1:3) We might chuckle at the prophet’s reaction (indeed, I think we are supposed to). But his story indicts us as well. May the Son’s grace increase within us our vital participation in His mercy, that we may be – and be known as – children of our heavenly Father.

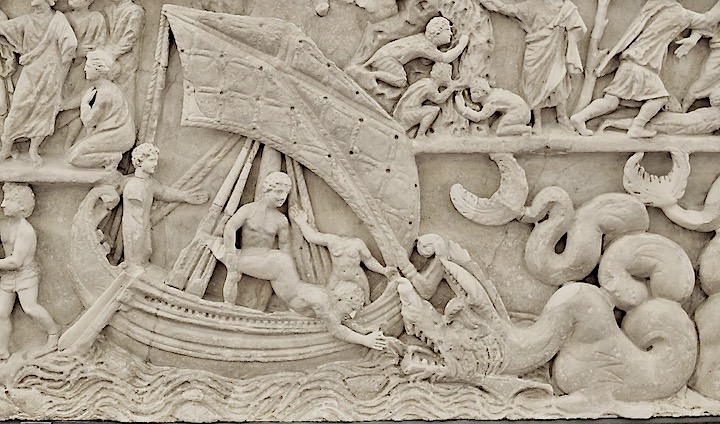

*Image: Sarcophagus “of Jonah” (detail) by an unknown artist, c. 300 A.D. [Vatican Museum] The prophet is cast from the ship into the maw of the “big fish.”