Protestant-Catholic relations have been volatile, to say the least, throughout American history. But in recent decades, there has been good reason for friendly collaboration. People of faith widely recognize Godless secularism as a common enemy. Hostility to religion has accelerated. With the COVID-19 shutdown, civic authorities in many localities have targeted churches for closure, but not, for example, liquor stores. Where is the pushback by Catholic leaders?

With Bishop Peter Baldacchino of Las Cruces, New Mexico as perhaps the only exception, Catholics now owe a debt of gratitude to their Protestant brethren, who are bravely leading the fight to restore worship to its rightful “essential” status.

Catholics are already indebted to the (mostly) Protestant Founding Fathers who gave us the Constitution and the Bill of Rights (although the Constitution is also grounded in Catholic England’s Magna Carta).

Hence, the First Amendment levels the religious playing field in the public square: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Americans, regardless of creed, share the common ground of religious liberty.

But differences in religions and institutional structures are instructive. In the 19th Century, Alexis de Tocqueville commented on the relationship between Protestants and Catholics in his book, Democracy in America. He observed that from the outside looking in, Protestants (perhaps unwittingly) viewed the Catholic Church as the culmination of the Christian faith. But from the inside looking out, the Church appears very weak indeed:

At the present time, more than in any preceding one, Roman Catholics are seen to lapse into infidelity, and Protestants to be converted to Roman Catholicism. If the Roman Catholic faith be considered within the pale of the church, it would seem to be losing ground; without that pale, to be gaining it. Nor is this circumstance difficult of explanation. The men of our days are naturally little disposed to believe; but, as soon as they have any religion, they immediately find in themselves a latent propensity which urges them unconsciously towards Catholicism. Many of the doctrines and the practices of the Romish Church astonish them; but they feel a secret admiration for its discipline, and its great unity attracts them.

The many examples of infidelities in the Old Testament make it inadvisable for any Catholic to rest on presumed laurels or triumphalism. The recent scandals involving sexual abuse within the Church have defaced the splendor of the Church’s mission. (In fairness, but not in justification, the rate of sexual wrongdoing is similar to that of every religious organization.)

The sex abuse crisis within the Church, along with an increasingly top-heavy bureaucracy, has – arguably – caused a kind of institutional paralysis (a contemporary Tocqueville might hesitate to speak so confidently of the Church’s “discipline” and the effective action such a discipline implies).

How else can we explain the general institutional failure to guard religious liberty during the pandemic? Historians will forever argue whether respect for the common good, fear of legal action, or servile fear, motivated Church authorities to meekly comply with government edicts. Regardless, the Church’s bureaucratic behemoth – and virtually every Catholic parish and entity – have submitted.

Not so with some independent Protestant churches in Texas, Florida, and recently in Kentucky.

The On Fire Christian Church – an evangelical Protestant church in Louisville, Kentucky – filed a temporary restraining order against the mayor. The filing seeks to block his prohibition on churches holding drive-in church services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such a quick response would be impossible today under the highly centralized Catholic Church. On Holy Saturday, the Honorable Justin R. Walker, District Judge of the United States Western Court of Kentucky granted a motion for a temporary restraining order.

With eloquent, incisive, and sardonic legal reasoning, Judge Walker begins:

On Holy Thursday, an American mayor criminalized the communal celebration of Easter. That sentence is one that this Court never expected to see outside the pages of a dystopian novel, or perhaps the pages of The Onion. But two days ago, citing the need for social distancing during the current pandemic, Louisville’s Mayor Greg Fischer ordered Christians not to attend Sunday services, even if they remained in their cars to worship – and even though it’s Easter. The Mayor’s decision is stunning. And it is, “beyond all reason,” unconstitutional.

After an erudite survey of American history and our nation’s quest for religious freedom, Judge Walker concludes with, “The Court does not mean to impugn the perfectly legal business of selling alcohol, nor the legal and widely enjoyed activity of drinking it. But if beer is ‘essential,’ so is Easter.”

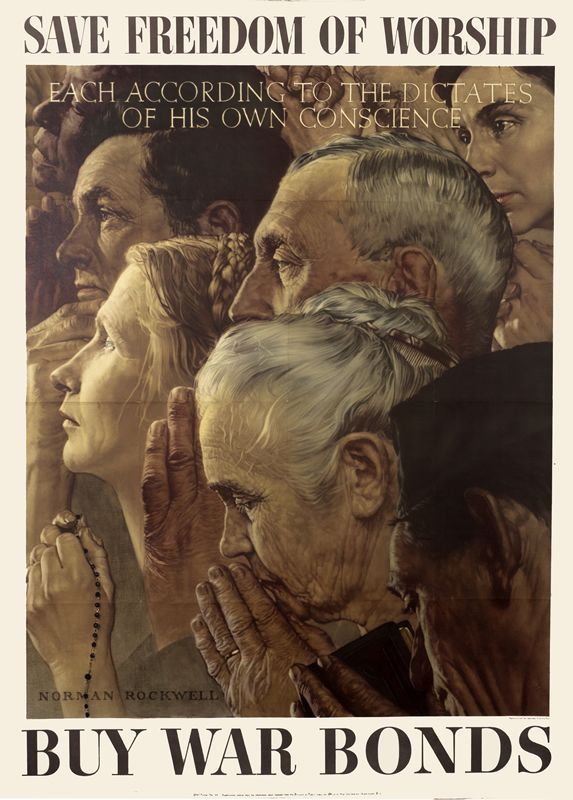

The judge’s eloquent defense of religious liberty brings to mind a wonderful (today, politically-incorrect) “ecumenical” poster by Norman Rockwell to promote America’s WWII war effort. There was a time in America when defending religious liberty motivated the taking up of arms. The poster depicts the faces of several ordinary Americans in prayer, including a woman with a rosary draped over her hands.

So for this round of Catholic and Protestant ecumenical relations, as the Catholic bureaucracy languishes, kudos to those independent churches like the On Fire Christian Church who are fighting the good fight for religious freedom.

“Let the beauty of the Lord our God be upon us: and establish thou the work of our hands upon us.” (Psalm 90:16-17, KJV)