Easter is the revelation of the truth of God’s gift of eternal life to us: Christ is risen, and those united to Him in a living bond of friendship in this life will be given the complete fulfillment of that union in the life to come in Heaven.

This gift of eternal life is given to the whole human person, body and soul. The saved will live forever with God: until the Second Coming of Christ to judge the living and the dead, the souls of those who have died in God’s grace await the resurrection of their bodies in either Heaven or Purgatory. The souls of the damned likewise await the resurrection of their bodies in Hell.

When Christ returns, the bodies of all men, women, and children who have ever lived will be reunited with their souls: the just will be united eternally, body and soul, with God in Heaven, the damned will be separated eternally, body and soul, from God in Hell.

The doctrine of the resurrection of the bodies of the dead at the Final Judgment is frequently not understood or appreciated by believers. We focus mostly on what happens to the soul when we die. We pray for the souls of the faithful departed “may they rest in peace.” It would be well to add “and may they rise in glory from their graves.”

You may have seen the pictures of the mortal remains of coronavirus victims here in New York being buried in Potters Field on Hart Island, just off the coast of The Bronx. The row of coffins, buried together in a long trench grave, is a striking image of death, but also of hope.

We treat the remains of the dead who have no one to claim them for private burial with dignity and respect. This is a societal manifestation of the Judeo-Christian inheritance that reverences the mortal remains of God’s highest creation on earth. Man, made from the dust of the earth, is placed back into that dust upon the completion of his earthly pilgrimage. His body will return to dust, but Christ has taught us that this is not the final word. Those bodies are his, in waiting, and they should be given a fitting resting place.

The worldview inherent in this burial practice was universally appreciated and accepted by Catholics until relatively recently, reinforced by the Church’s requirement to bury the baptized in consecrated ground, when possible, and by the prohibition of cremation, a practice alien to the Christian Faith.

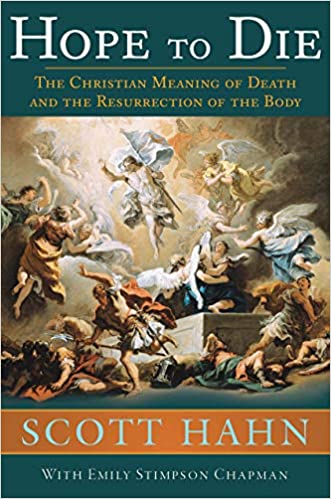

So it’s providential that Scott Hahn’s book Hope to Die: The Christian Meaning of Death and the Resurrection of the Body (co-authored with Emily Stimpson Chapman) has appeared during the current coronavirus plague. Hahn writes eloquently about the reality of death and the nature of heavenly life, and how we will be blessed to learn the meaning of everything if and when we attain the Beatific Vision.

But that vision is not simply a “spiritual” experience: “God will raise the dead – not just spiritually, but physically. After all, if the resurrection were just going to be spiritual, what happened to bodies in death wouldn’t matter. But with a physical resurrection, bodies matter. What happens to bodies matters. How bodies are buried matters.”

As a priest of thirty-five years, I have seen the rapid spread of cremation among Catholics. This has always troubled me, even though I accept that Pope St. Paul VI authorized this formerly forbidden practice in 1963. As Hahn notes: “To most Christians, for most of the past 2000 years, it was unthinkable that you would choose to utterly destroy bodies destined for glory and already touched by grace. . . .from the very first, Christians buried their dead as Christ had been buried.”

Indeed, Christianity developed a culture in which the graves of the dead are visited. The bones of saints are venerated as sacred relics. God, who made our bodies, never commanded that we burn the mortal remains of those who have died. By burying the dead in the earth we entrust that person’s body to God, just as we entrust his soul, which has temporarily departed that body.

Hahn reminds us of something that many have forgotten, or never knew: “[The Church] does not approve of cremation; it permits it. It does not permit the scattering of ashes or their retention in homes; it forbids it. It considers burial the most fitting way to care for the bodies of the dead until they rise again on the last day and urges us to follow that recommendation.”

Why this reticence about cremation? Hahn looks at what cremation, in contrast with burial, signifies, apart from the subjective intention of those requesting cremation: “Cremation teaches lessons about the body that are directly contrary to what the Church actually believes. It teaches that the body is disposable. It teaches that the body is not an integral part of the human person. And it teaches that the body has no value once the soul is gone – that body has run its course, and there will be nothing more for it. No resurrection. No transformation. No glorification.”

Most Catholics who cremate their deceased loved ones do so not because they reject the resurrection of the body at the Last Day. But our treatment of the dead should reflect our hope in the resurrection of the flesh. To be sure, God will resurrect the ashes of those who were cremated and reunite them with their souls. We cannot change or frustrate God’s plan for the human race. But we need to ask ourselves: why would we want to obliterate by fire the bodies of the dead that were sanctified in baptism?

Cremation is an essentially pagan custom. Christians should avoid it and honor God by honoring with reverent burial the mortal remains of God’s children who have gone before us, in expectation of that grand reunion of all mankind, our bodies and souls united again, at the Final Judgment.

*Image: The Last Judgement by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1904 [Crystal Museum, St. George’s Cathedral, Gus-Khrustalny, Russia]