Our late, and dearly beloved friend and colleague, Ralph McInerny, wrote an engaging memoir, as only he would write it, I Alone Have Escaped to Tell You: My Life and Pastimes. He remarked there on his early attraction to Thomism: “A good deal of philosophy is a matter of articulating what one already knew, what everyone knows, implicitly.”

His path of entry would come through Aristotle and Thomism, and that would be an enduring blessing. “Only later,” he said, “would I realize what an enormous advantage this was. Aristotle and Thomas were realists. They thought the human mind was a capacity to know the world and ourselves, the way things are. Your grandmother thought the same thing.”

A neighbor of mine, a graduate of Notre Dame, made a trip back there several years ago and encountered Ralph at the local inn. He reminded his former professor that he had taken his course on Aquinas. It took Ralph a moment to recall the fellow, but gave him this assuring word about the course on Aquinas: “It’s still true.”

One of the leading misadventures of modern philosophy, he thought, began with Rene Descartes; it came with the conviction that, unless our minds were first “rinsed in methodic doubt your grandmother cannot truly say she knows anything.”

Thomas Reid, that luminous figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, offered the apt commentary on Descartes as part of his exposition of that “common sense” that precedes all trafficking in theories. Descartes “would make us believe,” he said, that he escaped a contrived delirium about his own existence “by this logical argument: Cogito ergo sum.” [“I think, therefore I am”] “[B]ut it is evident,” said Reid, that “he was in his senses all the time, and never seriously doubted of his existence”:

for he takes it for granted in this argument, and proves nothing at all. I am thinking, says he – therefore I am. And is it not as good reasoning to say, I am sleeping – therefore, I am? Or, I am doing nothing – therefore, I am? If a body moves, it must exist, no doubt; but, if it is at rest, it must exist likewise.

In that vein, Daniel Robinson tellingly observed that the amnesiac doubts just who he is, but he doesn’t doubt that he is. That grasp of personal identity, as an anchoring truth, becomes the handle on others. And so as Reid would tell us, before the average man could banter with David Hume about the meaning of “causation,” he knew his own “active powers” to cause his own acts to happen.

Brown may earnestly plead to us that he is quite a different person now from the man caught embezzling last week. But he is, regrettably, the same man today that he was last week, even with his conversion.

In the early 1990s, however, the fallacy took on a more portentous meaning when I was invited to a workshop of the American bishops to discuss a challenge raised by some Catholic biologists over “delayed hominization.”

The object was to resist the conviction, thought well-settled, that when each of us was a “zygote,” no larger than the period at the end of this sentence, the creature brought forth in “conception,” we already had the genetic makeup that would define us as the same human being, in every cell and human attribute, through all of our days.

But the rival claim now was that the zygote, or the earliest embryo, did not have the full complement of features necessary to its completion as a human being. The argument was that certain molecules from the mother were also necessary to guide the development of the embryo, and they would be supplied only when the zygote became attached to the uterine wall.

And, of course, the upshot here was that, in this early stage, the embryo would not yet be that human “person” who might claim the protection of the law.

I had first heard about this from the late Andre Hellegers in Georgetown in the early 1980s and it gave rise to a commentary of mine, “A Funny Thing Happened to Me on the Way to the Uterine Wall.”

For no matter what changes were taking place, they were affecting this one unique being, bearing the same “identity.” What we had here, as I said, was a combination of “new science and ancient fallacies.”

When I first heard the term “delayed hominization,” my first thought, as I told the bishops was that it was something like “the fella says he will pick up his date at 6:30 and doesn’t arrive until 8 pm.”

But from another direction, Antoine Suarez, the physicist and philosopher, would point out that the embryo didn’t receive any distinct “message” or information from the mother necessary to steer its development: The “biological identity” of the embryo “depends basically on the information capacity of the embryo itself.”

Since the decision of the Supreme Court in the case of “transgenderism,” a crisis has rightly arisen in the circles of “conservative jurisprudence.” There has been a sudden awakening to the deficits contained in theories of “originalism” quite detached from those principles of natural law, or canons of reason, that the American Founders drew upon before they set to work in shaping the Constitution.

One of the leading minds among the Founders, James Wilson, a Scot immigrant, drew on the teachings of Thomas Reid in his lectures on law, and those axioms of “common sense” formed the ground of the natural law as understood by lawyers such as Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and John Adams.

Some conservatives still think of natural law as a foggy theory lofted in the sky. But the breakthrough comes these days as more of them come to see that the natural law is grounded in that same common sense that they use every day in the business of life as lived. And as Ralph McInerny would tell them, their grandmothers would still understand it.

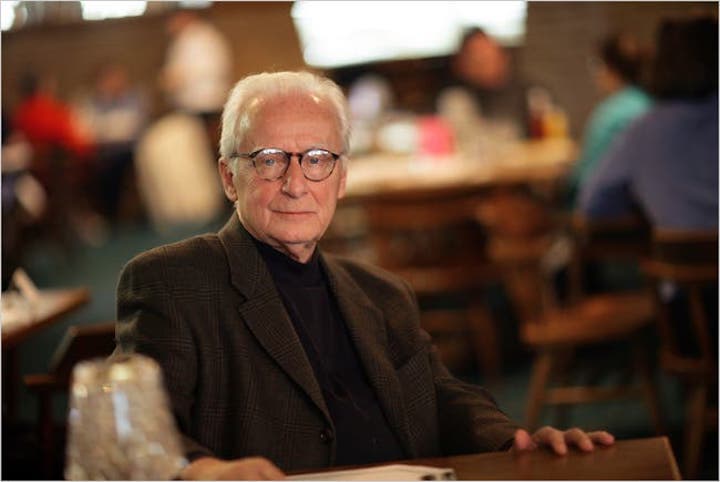

*Photo: Ralph McInerny by Matt Cashore (University of Notre Dame)