The release of the Vatican report on ex-cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s rise through the hierarchy prompted a modest but heartfelt chorus of voices, mine included, calling for a fresh look at how bishops are chosen. Most of the suggested reforms involved broadening the process beyond a closed clerical circle to involve observation and participation by the Church at large, especially the laity.

Fair enough. The system for choosing bishops really does need reform along these lines. But what might a practicable reform that met the specifications – more open and more inclusive – actually look like?

In seeking an answer, it’s best to start with the hints found in existing Church documents. But here, right at the start, we encounter one of the unsolved mysteries of Vatican Council II. It’s in section 37 of the Council’s theological centerpiece, Lumen Gentium, the dogmatic constitution on the Church. After making the point that laypeople should feel free to share “their needs and desires” with the Church’s pastors, the constitution says this:

By reason of the knowledge, competence or pre-eminence which they have the laity are empowered – indeed sometimes obliged – to manifest their opinion on those things which pertain to the good of the Church. If the occasion should arise this should be done through the institutions established by the Church for that purpose.

Imagine that – the laity not only have a right to opinions but sometimes even have a duty to express them. But here’s the mystery: Where are those “institutions” promised by Vatican II for use by the laity in expressing opinions to the pastors?

Certainly, there’s no shortage of opinions. Books, periodicals, web sites, and groups of all sorts, from advocates of women’s ordination to supporters of the Latin Mass, exist in abundance and provide a multitude of opportunities for lay Catholics to express themselves. What’s lacking, unfortunately, are processes and structures to ensure that responsible opinions responsibly expressed will be received, evaluated, and taken into account by the decision-makers. This lack is painfully evident in choosing bishops – surely one of those things that “pertain to the good of the Church.”

It’s safe to suppose that when Lumen Gentium 37 speaks of “institutions” for expressing lay opinion, it has in mind at least the diocesan and parish pastoral councils that Vatican II itself recommends in several places (see the decree on bishops Christus Dominus, 27, and the decree on the laity Apostolicam Actuositatem, 26). But although these bodies were established in large numbers and with much enthusiasm immediately after Vatican II, over the last several decades they have largely withered and disappeared, apparently for lack of interest. (In passing: wouldn’t it be worth a doctoral dissertation or two to find out why so potentially important an innovation, specifically endorsed by the ecumenical council, suffered this disappointing fate?)

Be that as it may, as early as 1985’s canon law commentary commissioned by the Canon Law Society of America found it necessary to remark that where the pastoral councils recommended by Vatican II didn’t exist, “some other institution may have to be established locally if the right to express one’s opinion is to be exercised in the Church.”

Needless to say, that didn’t happen. And, specifically, it didn’t happen when it came to allowing the laity a voice in choosing bishops.

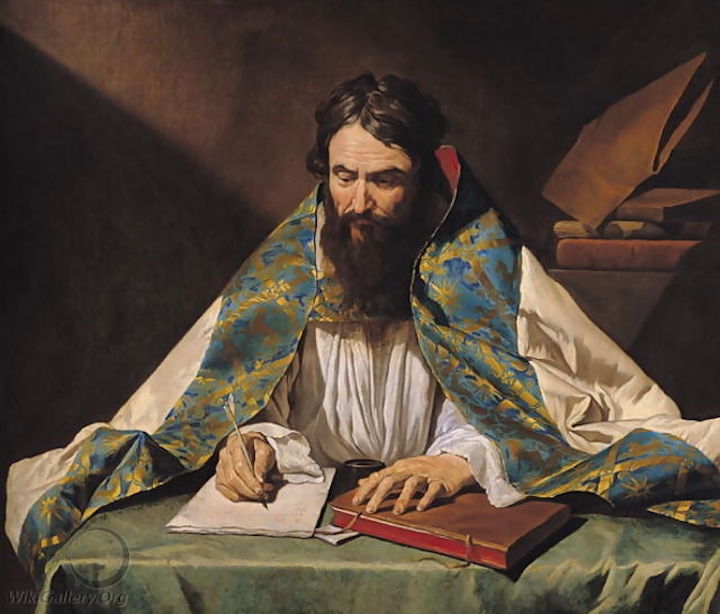

Nicholas Cafardi, a civil and canon lawyer, invoking the example of St. Ambrose’s election in Milan, provides a helpful overview of the current system of bishop selection, which operates in secrecy under clerical control. As a reform, he recommends that the papal nuncio, before sending Rome a list of potential candidates for a particular diocese, write to its priests and meet with its laity on weekends after Mass to get their input, including names.

Contacting the priests is a good idea, but meeting with laypeople after Mass isn’t workable. Even in a diocese of merely moderate size, it would take the nuncio or his representative many weeks – indeed, many months – to cover all the parishes.

My suggestion is different. Use the diocesan pastoral council (or establish one if none exists) to solicit suggestions from Mass-goers; a simple questionnaire inserted in the parish bulletin would do the trick. Parishes should also have the option of holding open meetings (initiated by the parish councils in parishes that have them) to let parishioners express their views. It would then be up to the diocesan pastoral council to synthesize the replies, add its own recommendations, and present the results to the nuncio for transmittal to Rome.

At this point, however, candor requires recognition of a disagreeable but indisputable fact: many lay Catholics don’t know enough about the Church, including their dioceses, to offer useful advice on choosing bishops or much else. That problem would be partially overcome by limiting consultation to the minority who, in Cafardi’s words, “actually participate in the life of the Church” by attending Mass regularly; and the process itself would be a helpful learning experience for them.

Saint John Henry Newman attracted no little attention – and criticism – with an 1859 essay “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine” in which he recalled that during the fourth-century Arian heresy, the orthodox faith concerning the two natures in Christ was “proclaimed and maintained far more by the faithful than by the Episcopate.” One would hardly make such a claim for many of today’s laity, battered by scandal, misled by dissent, and seduced by secularization, and now practicing their religion irregularly, at best.

But the hardy remnant who’ve stayed with the Church through it all deserve credit for standing firm in the face of today’s equivalents of Arianism. Shouldn’t those Catholics have a say on who their bishops will be?

*Image: St. Ambrose by Matthias Stomer (or Stom), c. 1635 [Musée des beaux-arts de Rennes]