By chance, I picked up Henryk Sienkewicz’s novel Quo Vadis from the family bookshelf last week, when I was looking for a next book to read for enjoyment. (How desperately we all need such reading now!)

But it wasn’t really by chance. I asked my guardian angel to guide me, as I often do, and nothing happens by chance anyway. Everything is under God’s providence. So, I thought, I’ll write something about this providential book.

I confess that I chose it against my inclination because, well, it has sold tens of millions of copies; movies have been based on it; and my children have been assigned it in school. Someone might think these are all good reasons to read it. But my personal inclination runs against the common and obvious. Maybe yours are against this book too, for other reasons?

Even after selecting it, I needed a couple of good rationalizations to get me started. And I found them: “Any book you have not yet read is the same as a book that has just been published” (Samuel Johnson). And, “As the grandson of peasants from a village outside Warsaw, you ought to learn more about Polish things whenever you can.”

Sienkewicz was a Nobel-prize winning author of a great trilogy of Polish historical novels. But Quo Vadis, as you probably know, is about Rome in the time of Nero. It tells a story of widespread, underground conversion to Christianity, from the viewpoint of the decadent and powerful pagans in control.

Sienkewicz researched ancient Rome extensively for the book, down to the smallest details of daily life. With a writer’s eye he weaves these details into his narrative, so that the book, while telling a great story, deftly imparts historical instruction about Rome, too. You might recommend Quo Vadis for pilgrims planning a visit to Rome; it makes the ancient city come alive.

But you can recommend it above all for Christians in the West who feel that some kind of insidious, post-Christian ideology is growing in power and threatens to oppress and persecute us. I do not mean merely that the book offers us consolation. Yes, Nero did dress as a bride in drag to marry a man, Pythagoras, in a big public ceremony (which Sienkewicz does not neglect to mention). But for all their corruption, the ideologues of our own Babylon the Great are not yet Nero.

I mean, rather, that the book gives us a picture of early Christians, whom we would do well to imitate. Let me draw attention to three notes.

First is the passion of those early converts. To become a Christian at the time of Nero was to fall in love with Christ so completely as to identify with him and prefer to die “with him” rather than to fail to live in his commandments. Sienkewicz conveys this passion ingeniously, by making a love-affair between a Roman patrician, Vicinius, and a Christian convert, Lygia, the central story of the novel.

How to convey what the love of Christ was for these first Christians? Tell a story of a man who would give up the whole world to possess a woman, and make that man’s love for that woman, and his love of Christ, one and the same. We need to love Christ, and one another, especially our spouses, in the same way.

Second is what I want to call the “self-sufficiency” of Christian fellowship and life for those early converts. For them, as Vicinius tells his pagan mentor Patronius, it’s as if Rome and Nero do not exist. All their thoughts are Christ, who is their sole Lord. They have discovered a path of life in Christ, and they live in the way Christ commands, and this gives them joy and is enough.

By contrast, today we might affirm theoretically that “the Church is a perfect society” but – how much we still complain! How much we speak as if we cannot be happy unless the times were other than they are! We do not seem overjoyed and fully satisfied that the love of Christ is already ours. (Yes, we should want to improve the world too – but as a sharing of what we already have been fully given.)

Third is the sense that the Christian life is de novo (“starting anew”) wherever it is found. What I mean is this. Perhaps some of us suppose unconsciously that things must get worse because we think of Christianity as akin to physical transmission, where each copy loses something of its original. A photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy, etc., eventually loses its information. But part of the miracle of baptism and the Eucharist is that the life of Christ is entirely, fully, and perfectly conveyed to any convert at any time.

In Quo Vadis you see that the Roman Christians have exactly the same devotion as the disciples did in the Holy Land, 2500 miles away. Take any saint, say, Angela Merici, whose memorial we celebrated last week – a humble girl called in the 15th century to love the Lord, as if out of nowhere, in a small town on the shores of Lake Garda. This is the life de novo of an alter Christus (“another Christ”).

Remember what St John Paul II insisted on conveying to the Church at the turn of the millennium: Iesus Christus heri et hodie ipse et in saecula, “Jesus Christ is the same, yesterday, today, and tomorrow.” (Heb. 13:8). These words still stand and always will.

Quo vadis as a Latin phrase is usually rendered “where are you going?” But the verb has the sense “rushing to.” And the phrase emphasizes the end point, not the motion. Am I agitated, distracted, working frenetically, or putting off work? Whatever I am doing: the end of all my activity, what is it? The novel suggests: If I am not putting away everything else to move quickly towards Christ, I am going away from him.

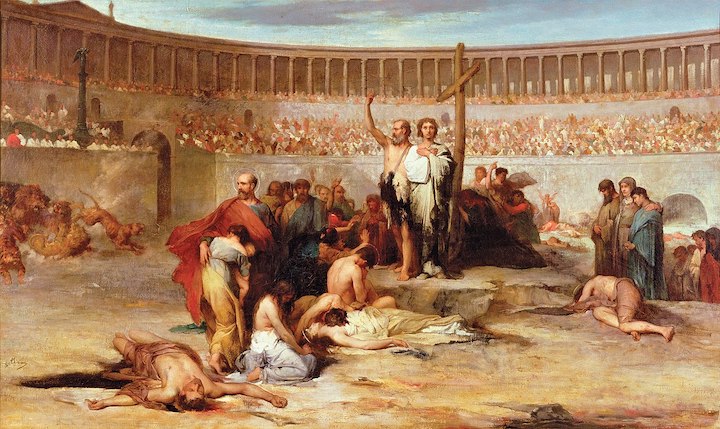

*Image: Triumph of Faith – Christian Martyrs in the Time of Nero, 65 AD by Thirion Eugène Romain, c. 1870 [private collection]