Painting is about transformation – of materials, of vision, and of consciousness – which is also a Catholic concern. Few Catholics notice places in Scripture such as, “Be transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Romans 12:2); and “The lamp of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light.” (Matthew 6:22)

It is wonderful how patches of paint on a flat surface can be arranged to look like three-dimensional objects, vast spaces, and even people in action. A flat, opaque surface transformed thus into a window is called a “picture plane.” It is the field in which an artist explores a transformed world and renders that world visible.

One particular kind of planar space projection, known as “artificial perspective,” was systematized and made known during the European Renaissance by Leon Battista Alberti in his 1435 book Della Pittura (”On Painting”). The Albertian perspective carried philosophical and theological implications, which can be seen in the use of perspective by Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, and other ingenious painters.

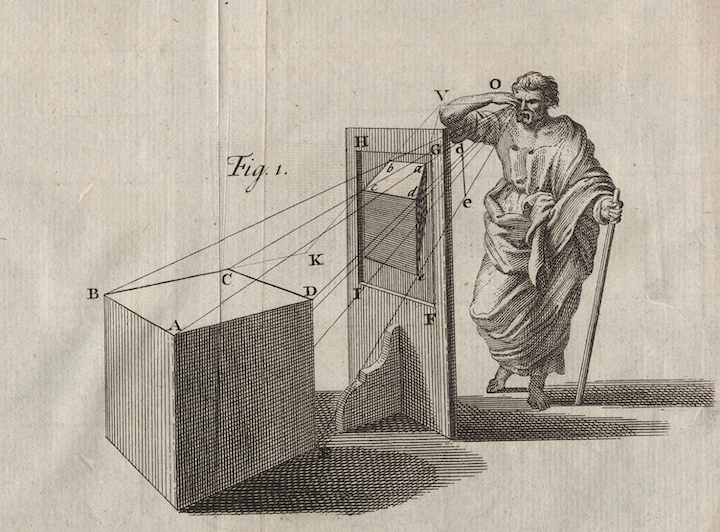

All the light rays that travel to our eye from the multitude of surfaces before us constitute a cone or pyramid. In perspective drawing, the picture plane functions as a window intercepting or slicing through the visual pyramid. Anyone could, in fact, execute a perspective drawing by standing motionless before a window, with one eye closed, and tracing on the window everything he sees through it.

Remarkably, all the edges – which in reality are perpendicular to the window (and thus to the face of the observer) – are found in their tracing on the picture plane to converge toward a single point on the viewer’s eye level. This “vanishing point” is understood as infinitely beyond visible space, and yet present to the viewers, always directly opposite them, and governing all things in the picture plane. This is the “alpha point,” the infinite source from which everything comes forth to meet human consciousness in the picture plane. It is also the omega point toward which everything in the picture plane recedes. Meanwhile, on the near side of the picture plane, the mind of the observer facing the infinite divinity can receive and assimilate all things that come from the divine source and pass through the picture plane.

In Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, for example, the general theological significance of perspective takes on a particular Christological and ecclesiological meaning. The vanishing point, infinitely distant in space, lies within the head of Christ in the picture plane, showing that in Him the apostles at the table are brought into communion with God. The Savior’s arms dramatize further that all comes from Him and returns to Him, the Alpha and Omega.

In the image above, a row of figures stretches across the foreground in the lower half of Fra Angelico’s fresco of Saint Lawrence Distributing Alms, while architecture fills the upper half. The receding columns of the nave of the church (the old Saint Peter’s Basilica) converge toward the infinity of God. What they encounter in the deep space is the apse, the place where God-with-us offers Himself in sacrifice upon the altar.

Marvelously, the shape of the apse continues down into the figure of Saint Lawrence, as the two form a rhythmic unit. The holy deacon who communes with God at the altar brings Christ’s charity to the needy. Lawrence has traversed the nave of the church where Saint Peter is buried. That nave with its many columns represents the tradition of the Church from its very founding.

Thus the saint mediates God, through the Church’s tradition, to the needy people gathered before the basilica’s door. In his luminous character as a Christian and an ordained minister, and in his loving action, he unites the vertical and horizontal dimensions of Christian life. His dalmatic is decorated with flames; the flames upon which he shall suffer martyrdom; but even more, the fire of divine love which unites his sacrifice with the sacrifice of his Lord always present on the altar in that apse.

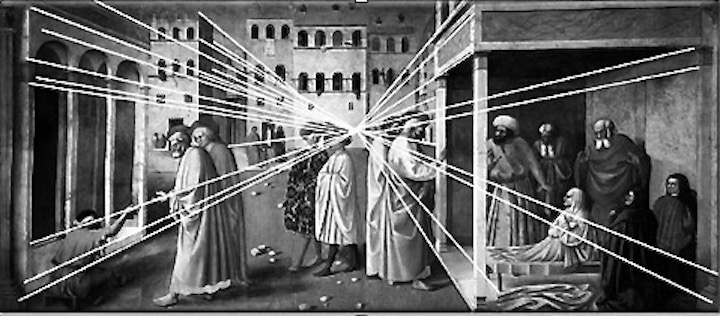

In Masolino’s fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence, Saint Peter is depicted in two separate episodes, on either side of a central vanishing point. A perspective line from the vanishing point runs through the apostle’s hand on its way to the hand of a crippled man on our left, just as the divine healing power is transmitted by the saint. To our right, Saint Peter tilts his head toward Tabitha.

A balcony’s supports on a distant building tilt at a precisely complementary angle as if in response, while the doorways on the same building rendered via perspective amplify the energy of the Apostle’s profile. The perspective edge where this building meets the street leads to the saint’s hand, which crosses a light pillar and touches a vertical area of hushed darkness.

The movement pauses here, and then a second light pillar, larger and brighter because of the perspective, amplifies the divine power in that blessing hand. Beyond this pillar, Tabitha sits up in her bed, now raised from death.

Many people think that the use of perspective is just a painter’s trick to suggest three dimensions on a surface where there are only two. But the transforming vision of Masolino shows us yet another dimension, “to them that love God, all things work together unto good, to such as, according to his purpose, are called to be saints.” (Romans 8:28)