I am not a good Catholic; and if I ever was, I was not aware of it. I suppose the best Catholics all claim this, though we should credit them with telling the truth.

You might know whether you were a good Catholic after your death, assuming the Catholic account of reality is true. But many of us aren’t dead yet, and haven’t the ability or the audacity to predict the future, or read the mind of God. Those who try may be dismissed as not good Catholics, by Catholic standards.

That the individual believer may be vain, smug, and pleased with himself, is a fact frequently noticed. But none of these qualities offers a very convincing imitation of a good person of any kind. Modesty, honesty, and discomfort are more likely qualities, and sometimes earn praise. But for that, they may be easily simulated.

Heroism, or in its religious form, saintliness, was omitted from the list of moral desirables; and if wanted I might recite the list of Christian Virtues, in opposition to the Deadly Sins. It is useful sometimes to be reminded of them. Consider: Faith. Hope. Charity. And, prudence, justice, temperance, courage.

The list cannot be sharply delineated. The cardinal virtues could be turned against the others. Conversely, one might analyze them into many precise parts. And if one wants, one may become entirely bewildered.

By comparison, the first three, theological virtues, have the curious quality of defeating our bewilderment; but only when they are taken with faith, hope, and charity. In this sense, they are divinely circular.

They do not tell us how to live, exactly. Returning to life is returning to confusion, where no “rules” will tell us our way, reliably. They give us a broad hint, of a kind higher than any intellectual reach, for they appeal simultaneously to the mind and the heart, awakening our moral sense.

While in hospital recently, I was wondering how to be a good Catholic. It wasn’t perfectly obvious, and as my mind was somewhat scrambled from the effects of heart surgery, I was inclined to put off difficult questions.

But I reflected that some questions could not be put off. Questions of faith and belief might answer themselves, and suggest humble prayer, but they did not constitute “a plan.”

I was aware that I had wasted my life, and would probably waste the rest of it, given my settled habit of “waiting.” I had been waiting for decades for something to happen, but nothing very important did. Was I just “playing out the clock,” as we say in athletics; although we do not usually do this unless we have the lead.

One of my well-wishers provided a hint. A creature of the Ottawa Valley, perhaps my age, he’d been left with nothing to do. He wrote poems, “collected” art on the Internet. and quotations from his reading. No one was likely to employ him, even though he did all these things well.

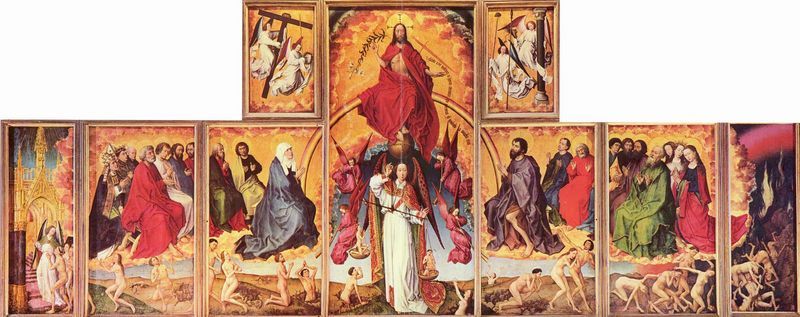

By pairing his found works with his poems, he made up a pretty little album, with the title “Postcards from the Valley.” The visual art was supplied by Rogier van der Weyden, Georges de La Tour, Stanley Spencer, Marianne Stokes, and many artists I hadn’t heard of; the sayings from the Bible to Bernard of Cluny to G.K. Chesterton to scraps he’d found in the press.

All were of a very high order, and his verse reflected the times and seasons that were depicted. There was nothing sentimental, or “Hallmark Card” about his endeavor, only good taste; and I received it as a surprise having expected something commercial.

I further discovered that he had produced his laminated compositions separately, printed on the back like memorial cards. These he left on park benches when he visited the city, and in other places, for people to find. His own name never appeared on them.

What a marvelous use of his time! And what a splendid evangelical action, for which no credit or payment is asked! The laminated cards are too small, and beautiful, for anyone to conceive of an objection.

The gentleman signed the album he sent to me, and others given to priests and admired friends, who would already know him. His anonymity was addressed to the world; it was not a statement of principle. For on some things, a name is unnecessary (as on most of the world’s art in previous centuries, and genuine folk art today).

I give this as an example, shown to me in answer to the question, “What should I do?” It wasn’t an “instruction” so much as a suggestion. One may think of a hundred things, by analogy to this, that one might undertake.

Each would amount to “a lark” by its author. For not only would he be unknown by his benefactors. He would be unknown later, in death. He would not have to be discovered; only his works would find the light of day; and be kept or discarded at other persons’ whims.

The Gospels were not written or distributed in this way. There is an urgency about their message; they would change the world. The first evangelists were of another kind, determined to prove their words, and bring them to the world’s attention. A spirit of heroism is carried in their voice. They did not leave cards on park benches.

For they were called, and knew themselves to be called, out of the pattern of an ordinary life. Likewise, Our Lady by the angel, Gabriel. We imagine he put it to her as a request; I’ve heard preachers ask, “What if she had said No?” But this shows a misunderstanding of the Gospel, for the question was asked of a person who would not say no.

It is modern and facetious. We have not been asked to be the Mother of God. We only ask ourselves to do something useful.

*Image: Beaune Altarpiece (or the Last Judgement) by Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1445-50 [Hospices de Beaune, Beaune, France]