“Taking every human design into captivity to the obedience of Christ” (2 Cor 10:5)

Michelangelo Buonarroti always insisted that he was a sculptor, not a painter. That he had imbibed stone dust with the milk of his wet nurse. That his sculpting only released the form, the design, il concetto already embodied in the block of marble that he worked with such passion. That he painted only under constraint and enforced obedience to a succession of popes, from the imperious Julius II to the more amiable Paul III.

It was Paul who conceived the project of constructing and then decorating the chapel that bears his name: Cappella Paolina. It was to serve as Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament and the place where the Cardinals would gather prior to entering Conclave in the adjacent Cappella Sistina. And he charged Michelangelo, the greatest artist of an age of great artists, to decorate the Chapel walls with depictions of the founding saints of the Roman church: Peter and Paul.

Michelangelo had recently finished the incomparable and revolutionary “Last Judgment” in the Sistine Chapel, and yearned to return to the work which had haunted him for a lifetime: the grandiosely designed and hubristically undertaken tomb of Julius II. But once more, he acquiesced to the wishes and dictates of a pope.

Thus, over a period of seven years, the Master toiled on what were to be his last paintings: “The Conversion of Saul” and “The Crucifixion of Saint Peter,” concluding his labors in his seventy-fifth year

Though Pope Paul himself seems to have been well pleased with them, the paintings themselves were met with incomprehension and even disapproval. The alluring celebration of physical beauty of the young Michelangelo’s creations – the monumental “David” and the depictions on the Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – now yielded to the seeming disharmonies of spiritual drama.

The “Conversion of Saul” represents the first act of the theo-drama. The ascended Christ is the center of radiating energy. No remote figure, he enters our world as disruptive grace. Christ’s mighty right arm hurls the proud Pharisee to the earth and also suffuses the prone figure with a new mysterious light. At the same time, the gesture of Christ’s left arm directs the soon-to-be apostle to Damascus, where a new identity (as Paul) and mission await him.

But the dramatic narrative suggests yet more. For beyond Damascus lie Rome and the Vatican hill. Indeed, the very chapel where the viewer stands is testimony to the drama’s denouement. By the ultimate surrender of self in the shedding of his blood, Paul consecrated the very ground on which the chapel stands.

There remains one more piece to the drama, intriguing if controverted. Contrary to the prevailing tradition, Michelangelo portrays the blinded Saul as an elderly man. Indeed, some have contended that the figure bears notable resemblance to portraits of the elderly Michelangelo himself.

Leo Steinberg, in his Michelangelo’s Painting, treats these last paintings at length. Of the “Conversion of Saul” he writes: “The artist is like the protagonist of his picture in past pride and selfhood, and in longing to undergo the apostolic ordeal – wanting only the assurance of grace. . . .His self-projection into the role of Saul is a petition.”

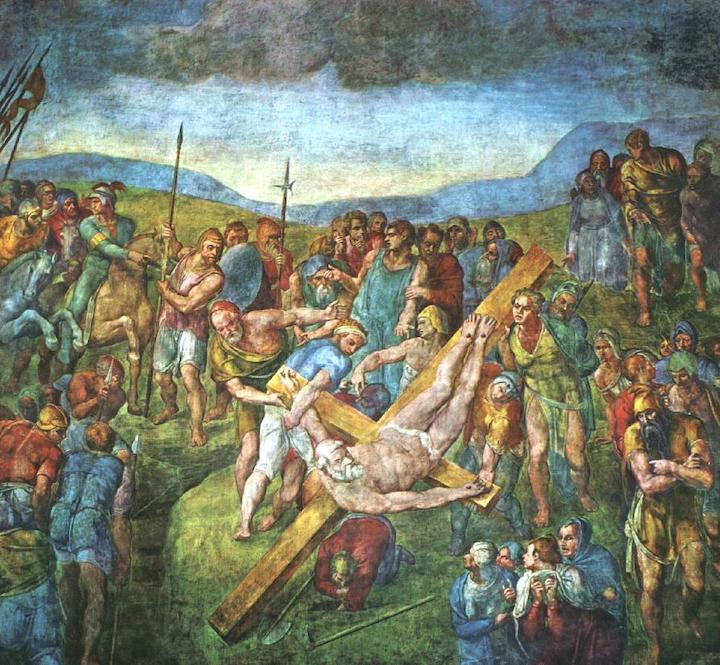

Michelangelo worked on his last painting, the “Crucifixion of Saint Peter,” from 1547 to 1549. Paul III scampered up a ladder to the scaffold to view the fresco in October 1549. Within a month the aged pontiff was called to render an account of his stewardship.

What the pope beheld was the massive figure of the man, whose ministry he inherited, affixed to a cross raised, as he requested, upside down. By a prodigious feat of will, the crucified Peter lifts his upper body, turns, and fixes his gaze upon the viewer.

Two observations help to appreciate Michelangelo’s striking achievement. First, the fact that he portrays the Crucifixion of Peter and not the Consigning of the Keys. It appears that Christ giving the keys to Peter was the originally intended subject, as befits a chapel associated with a papal conclave. Though there is no sure evidence, indications are that it was the artist himself who proposed the change in theme. That the pope acquiesced was evident sign of his affection and esteem for the artist

The second crucial observation is that Michelangelo’s depiction of Peter’s crucifixion broke in a radical way from the iconographic tradition, which portrayed the event circumspectly, the cross already embedded in the ground. Prior portrayals do not register the physical and spiritual energies in play (never separable for Michelangelo), either on the part of the antagonists or, especially, on the part of the protagonist himself.

For Michelangelo’s Peter is no passive victim, but an active participant, who in his death bears witness to and proclaims the crucified Lord who turns the world upside down. The ancient world, the viewer’s world, the artist’s world on the verge of being transformed.

In a brilliant analysis of the painting, Steinberg discerns a diagonal that descends from the Roman captain, upper left, pointing to Peter, through the transverse beam of the cross, to terminate at the outsize figure of the elder striding out of the frame and into our present.\

We recognize a clear resemblance between the figure in the fresco and that of “Nicodemus” in the great, unfinished “Pietà” which Michelangelo began to sculpt at night, after days of toil in the Cappella Paolina. The erudite, but uncomprehending, Nicodemus comes to Jesus by night and is instructed about the need to be “born from above of water and the Spirit” (Jn 3:1–8). In the “Pietà” he now embraces the crucified-living Christ – some even suggest in a posture of giving birth.

Significantly, both the figure of Nicodemus and the elder in the fresco bear the features of the artist.

Whether working in stone or paint, concept and design were for Michelangelo never abstract ideas, but bodily realities. The artistic embodiment ultimately involves and implicates the artist personally. Whether in his last paintings or his last “Pietà,” the supreme, excruciating art allows the Christ form to emerge from the recalcitrant marble of the self. To bring the self’s purposes and designs into alignment with those of Christ.

To view the Chapel and its artwork: www.vatican.va/various/cappelle/paolina_vr/]