When I was in high school my Latin teacher didn’t succeed in teaching me much Latin beyond the first three words of The Aeneid (“Arma virumque cano”). But one day he happened to make an incidental observation regarding the history of religion that has stayed with me. He said that nationalism, not Protestantism, is the most important and influential present-day heresy.

You may quibble with this assertion, arguing that nationalism is not, strictly speaking, a religion. For it doesn’t necessarily involve a belief in God or gods; after all, you can be an enthusiastic nationalist while at the same time being an atheist. But if a thing walks like a religion, and talks like a religion, and makes moral demands like a religion makes, and gives the kinds of consolations that a religion gives, then it’s a religion.

The great French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) recognized this when he defined religion as a set of beliefs and practices pertaining to “sacred things.” These things may of course be gods, but they may be things other than gods. They may, for example, be nations. For Durkheim himself – most of whose life fell between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I, decades during which millions of Frenchmen dreamed of revenge and of recovering Alsace and Lorraine – the supreme sacred thing was France.

France, for Durkheim and other French patriots, was very like God. It was in France that they lived and moved and had their being; it was France that gave meaning to their lives; it was France that dictated their moral code; it was for France that they were willing to kill and be killed. (Durkheim’s son, by the way, died in action in World War I.)

And this attitude of religious nationalism wasn’t limited to France. It was found in many other European countries. By 1914, thus, Europe had become a polytheistic continent, and the many gods were jealous of one another. World War I was nothing less than a battle among gods.

When the war ended, the most destructive war until that time in all of human history, many humane and humanitarian people – U. S. President Woodrow Wilson foremost among them – realized that nationalism had to be cut down to size. Something would have to be done to make sure that the many national gods, though continuing to exist, would live in peace with one another. And so the League of Nations was created. For a few years, there was much expectation that the horrors of World War I would never be repeated. But as the world soon learned, this was a foolish expectation.

During the even worse horrors of World War II, a new attempt was made to cut the national gods down to size. Once again, the American president, in this case Franklin Roosevelt, played the leading role, and in 1942 initiated what became the United Nations. More importantly, the nations of Europe, that perennial cockpit of war – especially between those hitherto deadly foes, France and Germany – began a process of co-operation that would lead gradually to the creation of the European Union. The EU is not exactly a United States of Europe, but many hoped, and still hope today, that a USE will eventually emerge. It would be a restoration of the ancient Pax Romana. The gods will go to sleep. Better still, they will quietly die.

But if the formerly ferocious gods of Europe have been asleep for a few decades, this sleep may have been no more than an afternoon nap. They are now waking up. Some parts of Europe are showing signs of a nationalistic revival – for example, England, which voted to secede from the EU; Scotland, where almost half of the people would like to secede from the UK; France, where Marine Le Pen is the leader of a strong anti-EU movement; Catalonia, most of whose citizens wish to secede from Spain; and a number of other places as well: Poland, Hungary, Austria, Italy.

In America, despite the internationalism of Wilson and Roosevelt, there was no generalized reaction against nationalism in the wake of either of the two great world wars. In recent decades, however, especially since the collapse of our great rival and foe, the Soviet Union, a kind of internationalism or anti-nationalism has arisen even here. Many liberal and broad-minded Americans, while continuing to be patriotic in a non-religious way, have come to think of themselves, not so much as citizens of America, but citizens of the world.

More recently among us, there has been a strongly nationalist reaction to this spirit of internationalism, notably in the rise of Donald Trump, who quite openly calls himself an American nationalist. This, I submit, is the basic issue at stake in the warfare between Trump-lovers and Trump-haters. It is a struggle between nationalists and internationalists. Its particular flashpoint has to do with illegal immigration. Nationalists quite naturally object to this phenomenon. Internationalists, being citizens of the world, have no little or no objection since they see undocumented immigrants as their fellow citizens of the world: “If I enjoy the benefits of living in America, why shouldn’t my fellow world citizens?”

Many reasonable people, including Pope Francis and many Catholic bishops, are alarmed at this resurgence of the old gods. They remember the nationalistic horrors of the 20th century. Who can blame them?

In the world of Europe and North America, however, where traditional religion (Christianity) has been in serious decline for a long time now, who can blame people who turn to the religion of nationalism? If it is better to have some religion than none, and if Christianity is becoming a less and less viable option in our most modern societies, it is understandable that people would turn in desperation to whatever gods are left.

But those gods are idols, and their worship a dangerous idolatry. May God save us from both the gods of nationalism and godlessness of internationalism.

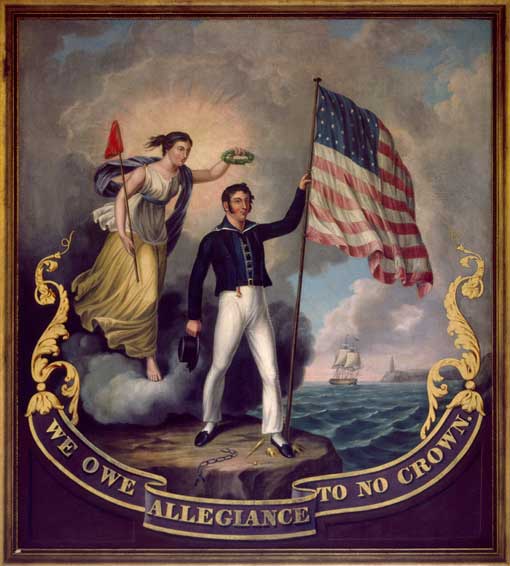

*Image: We Owe Allegiance to No Crown by John Archibald Woodside, c. 1814 [National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.]

You may also enjoy:

Robert Royal’s Something Stirring in the West?

Brad Miner’s The Risings