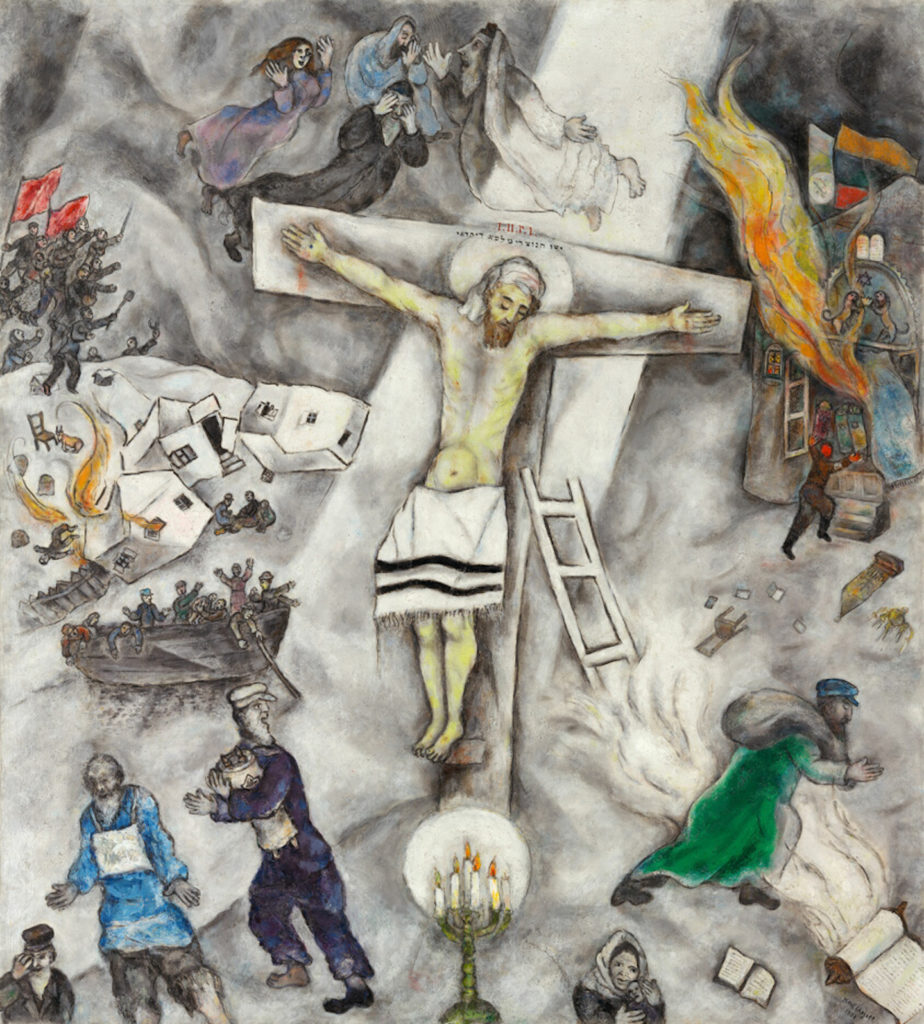

In Marc Chagall’s “White Crucifixion,” now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Jesus is in a tallit, the traditional prayer shawl worn by religious Jews, especially the Hassidim. He also wears the sort of headcloth a shepherd might wear. (All Jewish men traditionally cover their heads in prayer.) The barely legible inscription above Christ’s head is the Latin INRI and its Aramaic translation. A menorah is below his feet. Obviously, Chagall meant to emphasize the Jewishness of Jesus.

Scholar Ziva Amishai-Maisels of Hebrew University in Jerusalem writes that Chagall’s rendering of “Nazareth” (HaNotzri) in “Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews” was the artist’s double-entendre, the word Nazarene having become another name for “Christian.” Thus, Amishai-Maisels writes, Chagall “emphasized Jesus’s importance to both Christians and Jews, for the Jewish Jesus with his covered head and his fringed garment is also a Christian.” (Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 15, No.2, 1991)

(It’s interesting to note that in Arabic, the letter nun has been painted by ISIS on Christian homes in Iraq and Syria. It’s the initial letter of Nazarene and used by the terrorists to indicate those to be exiled or martyred. Nun or nün is written similarly in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic.)

In 1938, when Chagall painted “White Crucifixion,” European Jews were beginning to face the worst persecution in history. The Nazis had become Germany’s largest party four years before and, soon after, Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor. Jews had begun to be systematically deprived of civil rights beginning in 1934. The Office of Racial Policy was opened – home base of the “master race,” and Lebensborn was born, its purpose to promote racial purity, in part by breeding unmarried Aryan women with Aryan men.

Hitler rose from Chancellor to President to Führer. The Dachau concentration camp had opened in 1933. It was principally for political prisoners, but other camps soon followed, the intent of which was the efficient extermination of Europe’s Jews and other “depraved” peoples.

And through the Thirties and into the Forties, the world slept.

Chagall was living in Paris at this point, and news of the Kristallnacht pogrom and other attacks on Jews were the impetus for the creation of “White Crucifixion.”

On Kristallnacht (the “Night of Broken Glass,” November 9-10, 1938), thousands of Jewish stores, homes, hospitals, and synagogues had been attacked by the Nazi paramilitary group, Sturmabteilung (SA or Storm Troopers). About 30,000 Jewish men had been arrested and sent to the camps. All this and more Chagall packed into “White Crucifixion,” although he transplants the scene of the pogrom to his hometown, Vitebsk (present-day Belarus).

Chagall was aware of the danger into which such a painting would put him and his family, if and when the Germans took Paris. When that happened in 1940, the Chagalls had already fled to Marseilles, where they were detained by the Nazis. As if anticipating the 1942 film Casablanca, the Chagalls were on their way to Lisbon, whence they hoped to find passage to New York, which, thank God, they did. But not before Chagall’s crated paintings, including “White Crucifixion,” were briefly impounded: first by the Germans in Southern France, then by Spanish Fascists on the way to Portugal.

Chagall may have been naïve in thinking the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union, another bastion of antisemitism, would come to the rescue of European Jewry, but, apparently, that’s what we see in the mob with red flags entering top left in “White Crucifixion.”

The rest of the half-dozen tableaux surrounding Jesus are recognizable, even if we don’t entirely grasp the specific references. And we can’t blame the artist for then having a roseate view of Russia, his boyhood home. After all, the New York Times did. Chagall had been the Commissar of Arts for Vitebsk.

When he left the USSR in 1922, it was partly because he’d found himself on the wrong side of what it meant to be a Soviet revolutionary. As Talya Zax puts it, Chagall’s “hopefulness was a model for the hopefulness of his country, more fragile than any of the revolutionaries were willing to admit. For him and them alike, the balance couldn’t hold.”

And Russian antisemitism was obvious to all, and as Sarah Boxer – reviewing a biography of Chagall in the New York Times – writes, “Chagall’s blindness to Soviet horrors verges on the pathological.”

Chagall created at least 100 Crucifixion scenes over the years and did stained-glass paintings for churches. Yet there’s nothing to suggest he was a crypto-Christian. David Lyle Jeffrey notes, however, that Chagall was a close friend of Raïssa Maritain, wife of philosopher Jacques Maritain (both Catholic converts: she from Orthodox Judaism and Jacques from agnostic Protestantism). She said of Chagall that he always painted “Christ étendu à travers le monde perdu” (Christ spread across the lost world).

Whether he thought of Christ as simply an extraordinary, ethical first-century Jew or, less likely, the Messiah, for Chagall Jesus always represented hope, which means there’s truth in the painter’s work.

It’s certainly the case that Chagall principally painted Christ crucified for political reasons. As Professor Amishai-Maisels writes, Chagall was never trying to “depict the Christian Messiah. . .but the Jewish martyr who holds out no hope of salvation.” Not, anyway, in the world as Chagall saw it then: one in which Christians themselves had forgotten Christ’s message of peace and brotherhood.

Still, it was a lifelong passion. Chagall had painted his first Crucifixion, Golgotha, in 1912 (now at MoMA in New York). He kept painting them into the early 1970s.

Today, Jews and Christians alike, unified in Biblical tradition, are increasingly subject to persecution and not just in the birthplace of both religions – those hostile places that surround the Holy Land – but also in all our contemporary Roman Empires, where new, secular gods arise to challenge God.

It simply remains to say that “White Crucifixion” is one of two favorite paintings of Pope Francis, the other being “The Calling of St. Matthew” by Caravaggio. The pope has some good artistic tastes.

*Image: White Crucifixion by Marc Chagall, 1938 [Art Institute of Chicago]

You may also enjoy:

Robert Royal’s Grandparents, Great-Grandparents, and the Great Tradition

Michael Pakaluk’s Circumcision for Christians