For many, perhaps most people, human life is not worth very much. Our sentiments, and sentimentality, cloud the issue from ourselves.

We think we should take murder, for instance, quite seriously, given the chance of being murdered ourselves; but no, in practice we don’t. The imagination does not work that far ahead. So long as the victim is not a close relative or good friend, and we don’t have to witness the deed, we tend to greet the result with indifference, or at best with mild curiosity.

Yes, we are against killing, human beings in particular, in most instances outside of war. We are in favor of it only at exceptional moments. Some of these are – or were until recently – recognized in law, or even when not, generally approved. As the old Texans explained, some persons “need killin’,” and the person who carried out the execution was excused.

Those who read (books), or go to movies, are familiar with the dramatic rules. We have a general idea about when to cheer, when to express horror, and when it is time for a commercial break. This in turn prepares us for the less dramatic or more real encounters.

When the audience turns its attention away from the depiction of a crime, and we turn it inward instead, our amour-propre comes into play. We want to be seen reacting in the approved manner, and neither laughing nor weeping out of place. Even those who do not care who lives, and who dies around them are eager to be sensitive to appearances and to pretend.

For while people do, habitually, still disapprove of murder, as grand principle – or at least pretend to do so – they will not pretend to approve a lapse of taste.

This is why serial murderers become unpopular, even when they have taken the precaution of choosing their victims carefully. For such killing is seen as what the British call “poor form.” In today’s society, still, but in any society of which I’ve been made aware, questions of taste take priority over psychopathic events.

The general “secular” or as some say “pagan” attitude to death, including by murder, yields two propositions. Number one: we don’t want to see it. And number two, we don’t want it to happen to someone we care about (as opposed to someone merely familiar). But outside these two criteria, death is what used to happen in newspapers, and now happens less sensationally, online.

The importance of death has receded from daily life. This has been known and accepted for some time. The provision of professional services (“undertakers” and the like) to dispose of the dead, quickly, silently, and without unwelcome provocations, has changed the world from what it was in generations past.

Death has been, as it were, sterilized, though it sometimes happens a little too suddenly to be managed well. This may be the occasion of some screaming and hysteria, but with professional interaction, the excess can be tamed. We even have “grief counselors” for those unable to negotiate a “passage.”

And increasingly, the bodies of the dead are made invisible by cremation, or by the more environmentally-friendly rival disposal systems.

Today, for instance, an aunt or uncle one wants quickly to forget may be dissolved by aquamation, or given a shallow “green burial” among the hungriest worms, or could be stuffed into a patented mushroom suit that is the decompositional opposite of a plastic bag.

Indeed, “human composting” has (according to an advertisement) become more popular, given environmental concerns over the global-warming effect of carbon fuels used in cremations. Apparently, several jurisdictions now approve burial in shallow graves or “curing bins,” where bodies may be made into healthy soil, to insert under forests.

There is still a problem, at least in theory, from non-bio-degradable (incorruptible?) tombstones and similar graveyard impedimenta. But various clever recyclable or soluble markers will wash away without leaving toxins. Had I received some environmental training, I might understand what they are.

But in addition to making the human “footprint” smaller, it will be necessary to reduce the number of human feet. Thoughtful packaging for the dead may be well-intended, but there are environmental concerns about the packaging too.

I think much of the riotous anger directed at judges, and the Republican politicians who appointed some of them, is from this sort of concern for the planet. How will nature be restored unless the people now contaminating the earth are killed off?

Abortion represents the most efficient means, before a lifetime of consumption can be started. Moreover, the aborted fetus is rendered disposable while it is still very small, and hospital systems seem already sufficient for making the little ex-organisms disappear.

At the other end of the metabolic series, Canada now leads the way with our “MAID Service,” or Medical Assistance In Dying. A news item mentioned a young lady in British Columbia who has signed on for the service, she says, because getting the alternative medical treatment for her condition is more than she can afford. (It would involve travel.) Canada’s socialist medical system has created a number of such paradoxes.

Presumably, the MAID service and a body-disposal arrangement can be combined by the authorities, or by an enterprising franchise operation as the market for eco-deaths expands.

As usual, the Catholic Church is (mostly quietly) resisting progress on this front. She cannot approve of murder, no matter how favorable or indifferent the public becomes, or how loud and violent the demonstrations. She continues to cultivate the backward idea that human beings are somehow significant, including the ones who are currently out of view. She is a stickler for rules that are impossibly slow to change.

So, I continue to be Catholic, even towards people I dislike.

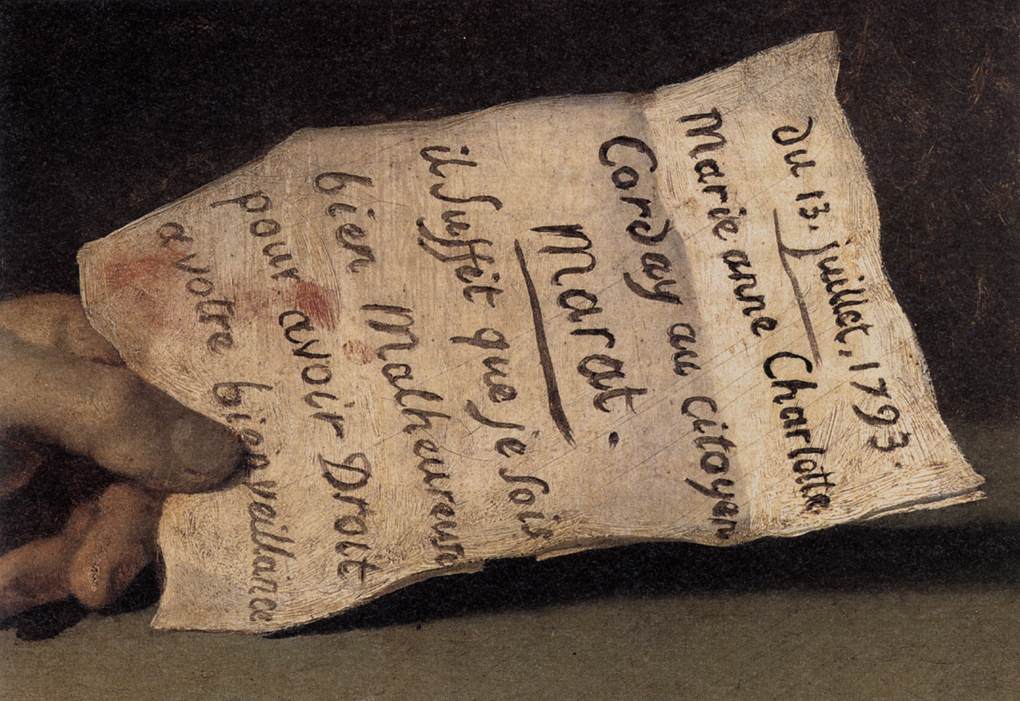

*Image: Marat Assassinated by Jacques-Louis David, 1793 [Royal Museum of Fine Arts Belgium, Brussels]. Below is a magnification of the paper in Marat’s hand, which identifies his killer and then reads, “Il suffit que je sois bien malheureuse pour avoir droit a votre bienveillance“. That means, “Given that I am unhappy, I have a right to your help“.

You may also enjoy:

Matthew Hanley’s Organ Transplantation and Euthanasia

Randall Smith’s They Do Death Well Here