In the wake of the Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade, pro-abortionists are using all sorts of scare tactics to suggest that the ruling and the justices who formed its majority imperil American “rights” and “liberties.” Despite Justice Alito’s assurances that Dobbs is about abortion, fear-mongers cite Justice Thomas’ concurring opinion – in which he attacks the legal notion of substantive due process and not the ethical issues to which it has been applied – to intimate that laws banning interracial marriage are lurking in the wings.

We need to shift that discussion, on its merits, elsewhere. That elsewhere is the notion of “procreative liberty.”

“Procreative liberty,” as developed by the Supreme Court, has been highly individualistic and largely negative. Those assumptions deserve challenge, both because they are unscientific and because they have excluded other legitimate interests.

The shift to a highly individualistic concept of “procreative liberty” began in Eisenstadt v. Baird, a 1972 contraception case. The Supreme Court struck down Connecticut’s unenforced ban on the use of contraception by married couples in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), claiming that access to contraception was protected by a marital “right to privacy.”

But seven years later, that Court invalidated a Massachusetts law that restricted access to contraception by unmarried persons. Without getting into the merits of the Bay State law, the main point is the shift that procreation should be seen primarily, if not exclusively, through an individualist lens, which abandonment of the “marital” aspect emphatically did.

That approach needs to be challenged, first of all, because it is unscientific. As Ryan Anderson notes in his book When Harry Became Sally, the reproductive system is the only one of nine systems of the human body that is not autonomous. It is the only system that requires another person to function. You can breathe, circulate blood, and digest your dinner autonomously. But you can’t procreate by yourself.

Apart from the direct involvement of another person in the procreation of a human life, Western culture has always also assumed a social interest in procreation. Society’s very existence and continuation as a whole depends on what Irving Berlin called “doin’ what comes naturally.”

Elite 1972 America believed Paul Ehrlich’s call for Zero Population Growth lest the “population bomb” explode and turn the world into the “Star Trek” planet Gideon, filled with wall-to-wall people. Ironically, as even Elon Musk has recently recognized, the West today is far more threatened by “demographic winter.”

This individualistic approach to “procreative liberty” constantly asserted itself, even when the Court denied it was doing that. Thus, in Roe v. Wade, Justice Blackmun threw a bone to critics by claiming “[t]he pregnant woman cannot be isolated in her privacy” (410 US 113 at 159).

Yet that is precisely what the Court spent the next forty-nine years doing. It insisted that fathers had no say in the fate of their unborn child because the state could not “delegate” a veto power to them, a bizarre notion since fatherhood preceded the state and, therefore, did not need the state’s delegation to ground paternal interest.

It denied parental rights to approve or even to know of a minor child’s abortion. It struck down state efforts to stop killing the handicapped by banning eugenic abortions, motivated by discriminatory intent that would be absolutely illegal one minute after birth.

In the wake of Dobbs, we can hope to begin overturning such case law that bludgeoned paternal and parental rights and legitimated prenatal discrimination, particularly against unborn handicapped and female babies (the victims of most sex-selection abortions are girls).

The Court’s invention of “procreative liberty” was largely negative, mostly because until 1978, pills or abortions prevented or ended pregnancies. That negative individualist taint perdured, even after reproductive technologies reduced fathers to sperm donors and mothers to egg donors or uteri for rent.

Thus, in Davis v. Davis, the Tennessee Supreme Court, operating on Roe’s unscientific foundations, which pretended that the question of when human life begins is insoluble, ruled in a divorce case where custody of frozen fertilized ova was at issue, that Junior Davis could not be compelled to “become” a father. (News flash to Junior: you already are).

“Procreative liberty” has largely been framed in terms of preventing or ending lives of children to meet an adult’s wishes.

The advance of reproductive technology, however, poses new questions about individualistic “procreative liberty.” If procreation – despite the science and “doin’ what comes naturally” – is to be understood in terms of individual choice, then no child has a right to two parents, to a father and mother, to a genetic relationship to those parents, or to be conceived and to come into the world as children have come into the world from time immemorial.

Children and their rights are subordinated to an adult’s or adults’ whims, preferences, and “choices.” But, as Michel Aupetit, the ex-Archbishop of Paris pointed out, when children become a “parental project,” they must inevitably be reified, because they ineluctably turn into products that meet (or don’t meet) others’ specs.

Is that what we want as a society?

Fear-mongering aside, the reversal of Roe might remove constitutional straitjackets to a discussion of those questions, including what kind of society do we want for children?

Getting to that discussion will take time and effort because powerful forces want to maintain the “procreative liberty” regime of which Roe was the culmination. And many other Americans either have not or cannot imagine any other way of arranging things.

But the effort to do so is imperative, because it’s a question not of adults who, like kids, insist on demanding what they want, but it’s all really about the children.

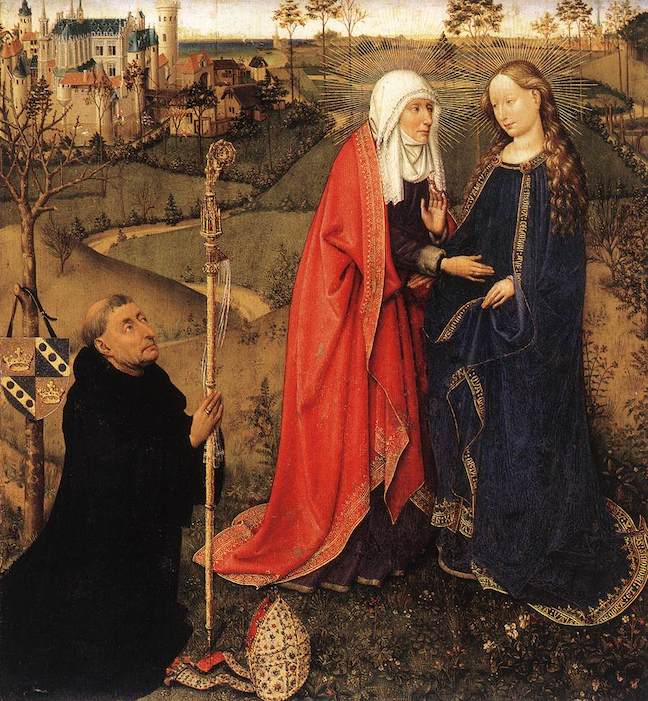

*Image: The Visitation of Mary by Jacques Daret, c. 1435 [Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany]

You may also enjoy:

Anne Hendershott’s Reaping What We’ve Sown

Randall Smith’s Neither the Seamless Garment, Nor Merely Anti-Abortion