Increasingly, in our society of autonomous, expressive individualism, all utterances are taken to be expressions of one’s identity and individuality rather than statements about the world that might be judged true or false. As James Bowman notes in a recent article, people now identify themselves with their opinions to such a degree that “to change or modify those opinions in the light of further knowledge or understanding would amount to a kind of self-annihilation.” Disagreement that might have at one point been taken to be disagreement about facts are increasingly taken to be clashes of personal identity.

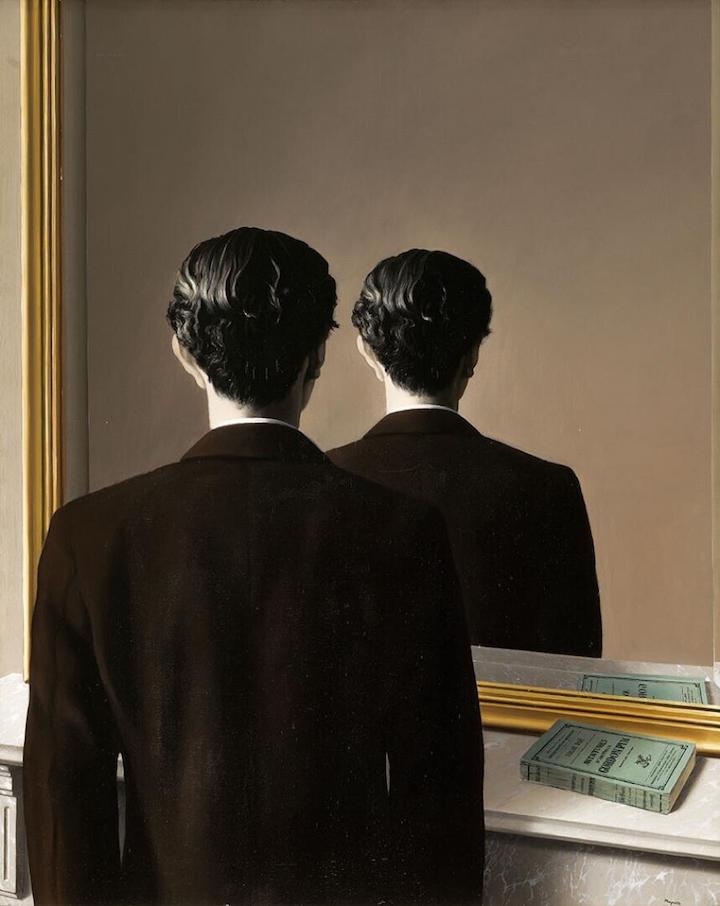

Increasingly, a culture of autonomous expressive individualism makes us less capable of seeing things (or even imagining we ought to see things) from other people’s perspectives. We increasingly lack the ability to see others as they see themselves. And for related reasons, we can no longer see ourselves as others see us, which, as numerous studies have shown, is a critical way of coming to know ourselves.

So, for example, Bowman takes note of the subhead to an article on the NBC News website that said: “It’s not uncommon for people to delude themselves into believing that their preferred political side is the reasonable one.” True. But in the article, the writer complained about Elon Musk and “how out of touch he is with political reality.” It seems never to have occurred to this writer that these words might apply equally to herself.

Does the writer of this article – do we all – owe our fellow citizens and interlocutors something more? This question brings us back to a central feature of autonomous expressive individualism: the conviction shared widely that we owe nothing to others but what we choose.

People justify their refusal to listen to others, saying things like: “Perhaps I am not as open to other views as I might be, but I have no wish to be open to opinions like that – from people like them!” Is it really wrong to refuse to listen to – fill in the blank – “deplorables” or “rich, elite, bleeding heart liberals who exempt themselves from the rules they pass for everyone else” or “rich, selfish conservatives who don’t care about the poor”? You probably know how this game is played. The problem is that the game is played by both sides.

I once had a nice man send me a note in response to an article I’d written in which he said, “The problem our country faces now, unfortunately, is that one political party (I’ll let you guess which one) is harboring, protecting and supporting a violence-propagating, anti-government, anti-democratic, and quite frankly fascist faction that is only growing within its ranks.”

The problem with having me “guess which one” was that I have, over the years, received nearly identical notes from the members of both political parties. When I pointed this out to him, the gentleman wrote back to say he didn’t want to hear any false equivalences between the two parties. When I wrote to inform him that the people from the other side made the same complaint about “false equivalences,” he was unmoved.

It was absolutely clear to him who the problem was, just as it had been absolutely clear to the people on the other side. The two sides were pointing fingers at each other, which, to my mind, made them both right.

Personally, I have no wish to deny that there are problems on both sides, but also legitimate concerns on both sides. This is not quite the same as creating a “false equivalence.” In my opinion (for what it is worth), the one side has been worse on certain things, and their opponents have been worse on other things. What worries me the most, however, is that neither side can see the perspective of the other, nor could they even imagine that there might be something to be gained by doing so.

Those on both sides increasingly see no point in presenting solid evidence or arguments. Simply stating their view, simply expressing it, is supposed to be enough to compel acceptance, much the way each person’s expression of him- or her-self is supposed to be accepted by all.

Saying “Mitch McConnell is an idiot” is like saying “I am gay.” You say it, and then people are supposed to affirm you. As a consequence, it increasingly seems to many people that the only way anyone would persist in rejecting the wisdom and goodness of the position they advocate is if their opponent is either a fool or a scoundrel.

We say, “What sort of person would draw that conclusion?” (the presumption being that it could only be an evil one) rather than, “How could a sensible, reasonable person come a conclusion different from mine? Have I missed something? What does this person see that perhaps I don’t? Why, apart from evil intentions, might this person have come to the conclusions he has?”

I learned chairing committees to say, “Everyone has a voice, no one has a veto.” I said this because some of the people on the committee or those coming before the committee thought that once they had made their speech and staked their claim, the rest should be pro forma acceptance. But democracies don’t work that way. You make your case; you sit down, and then others make theirs. Sometimes you convince people, sometimes you don’t. They aren’t required to accept your view.

The question we must face now is whether partisans on either side are ever willing to accept losing a vote, whether in a general election, the legislature, or the Supreme Court. If not – if arguments and evidence have ceased to matter and every dirty trick becomes acceptable to obtain victory over one’s opponents – then you need not ask which is the “violence-propagating, anti-government, anti-democratic, and quite frankly fascist faction” in America.

Just look in the mirror. We have met the enemy, and he is us.

*Image: Not to Be Reproduced by René Magritte, 1937 [Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands]

You may also enjoy:

David Warren’s The Counter-Culture

Rev. Jerry J. Pokorsky’s A Temptation: The Cult of Personality