Sad news, kids: Our safety’s been compromised. The Biden administration’s Department of Homeland Security has formally pulled the plug on its “Disinformation Governance Board.” As noted on August 26 by the Wall Street Journal,the board was formed “to counter disinformation deemed a threat to homeland security.” Such threats were said to involve, in part, “misleading information used by smugglers to persuade migrants to travel to the U.S.-Mexico border and disinformation spread by foreign states such as Russia ahead of midterm elections.”

The board’s intentions, we’re assured, were entirely pure. Its name, straight out of Orwell, was supposedly a regrettable gaffe. Only civil liberty eggheads, religious freedom fanatics, and right-wing yahoos would see a dark side to an unelected group of federal bureaucrats tasked with deciding what’s true and what isn’t.

But let’s get serious.

The distinctive marks of our second “Catholic” presidency, so far, are a high degree of mental confusion; a vigorous, even vituperative, support for easy abortion; non-enforcement of borders and inconvenient laws; an appetite for social control; and an overripe loathing of Mr. Biden’s predecessor.

Political hardball has always been a bipartisan American sport. Republicans in general, and Donald Trump in particular, are hardly virginal when it comes to massaging facts. But the systematic lying of the last few years from the left – remember the phony “Russia collusion” scam shopped by Mr. Trump’s congressional critics, and kept on life-support long past its expiration date by congenial media and federal agencies? – sets a new standard of mendacity. Thanks to everyone on the ecclesial Left, by the way (let’s not forget jewels like this), who helped make this mess possible.

My point, though, is not just another bombing run on the Biden-Pelosi tribe. Both leaders are entirely political creatures. Power – its pursuit and its exercise – is the framework of their lives. So maybe they know not what they do. In effect, they’re symptoms, even more than a cause, of our homeland’s current moral disorder. And on the national level, that sickness of the soul may now be unfixable, which sounds bleak but is actually the opposite. Our environment, for all its problems, is an invitation to clarity about our Christian fundamentals. Put simply: What do we really believe, and what are we going to do about it?

Here’s the good news: We’re hardly the first Christians to face those questions, or the problems that create them. Some extraordinary people offer us an example of how to respond. Among them is a “Václav;” in this case not Václav Havel, but his friend and colleague in resisting Soviet bloc repression in the 1970s and ‘80s, Václav Benda. And Benda, in some important ways, is the more interesting man of the two. His essays in The Long Night of the Watchman, written in the teeth of persecution by a regime seemingly impervious to criticism or change, are an antidote to despair.

Like Havel, Benda was a tireless Czech dissident. Unlike Havel, Benda was a committed Catholic. The Soviets crushed Czechoslovakia’s brief “Prague Spring” in 1968. But the country’s dissident movement soon grew into three allied wings: political, cultural/artistic, and religious.

Benda was a leader in the religious wing. He was an early signer, active member, and spokesman for Charter 77, the Czech human rights organization. He also co-founded VONS, the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted. Jailed in 1979, he spent four years in prison. During his absence, his wife and children opened their home to an endless stream of persons hounded by the authorities. They continued his work with Charter 77 and VONS.

The totalitarian instinct – the appetite for social control – morphs and adapts across cultures and time, exactly like a virus. Democracies are not immune. Benda had no illusions about the moral health of the modern West. For Benda, as the editor of The Long Night notes, the irreligious thought-world of the West was preferable to the Marxism of the Eastern bloc in the same way a wounded organ is preferable to a malignantly tumorous one. The former might be healed; the latter, not.

Ironically, one of Benda’s most moving essays – written in the midst of his political miseries – is titled “Not Only Moral Problems.” It’s a forceful defense of Catholic teaching on contraception, divorce, and abortion. Given the troubling recent work of the Pontifical Academy for Life, it would make excellent, medicinal reading at the Vatican.

Benda is best known for his 1977 essay “The Parallel Polis.” Václav Havel and other dissident leaders borrowed heavily from its ideas. Benda argued for a strong moral witness against the evils of the ruling regime. But he also said that witness wasn’t enough. Reform from above was unlikely. So he pressed for the construction of an alternative, “second culture” closer to the real life and needs of the people; a parallel polis (i.e., community) with parallel structures to the harmful official ones, and designed to one day replace them.

The specifics of his plan were written forty-five years ago for a state very different from our own. But his basic insight – the need for a second culture of friendship and truth to counter a dominant culture of loneliness, conflict, and systematic lies – is more urgent than ever.

Benda died in 1999, a decade after his nation’s Velvet Revolution. But his example, and the Catholic faith that sustained and guided him, speak directly to us today. The elements Benda saw as essential to totalitarianism – “the atomization of society, the mutual isolation of the individuals, and the destruction of all bonds and verities which might enable them to relate to some sort of higher whole and meaning. . .beyond pure self-preservation and selfishness” – are more elegantly disguised and more shrewdly marketed in America in 2022. But they’re just as real.

And yet, we already have the second culture we need. It’s called the Church. We just need to live our faith as Benda did. In other words, like we really believe it.

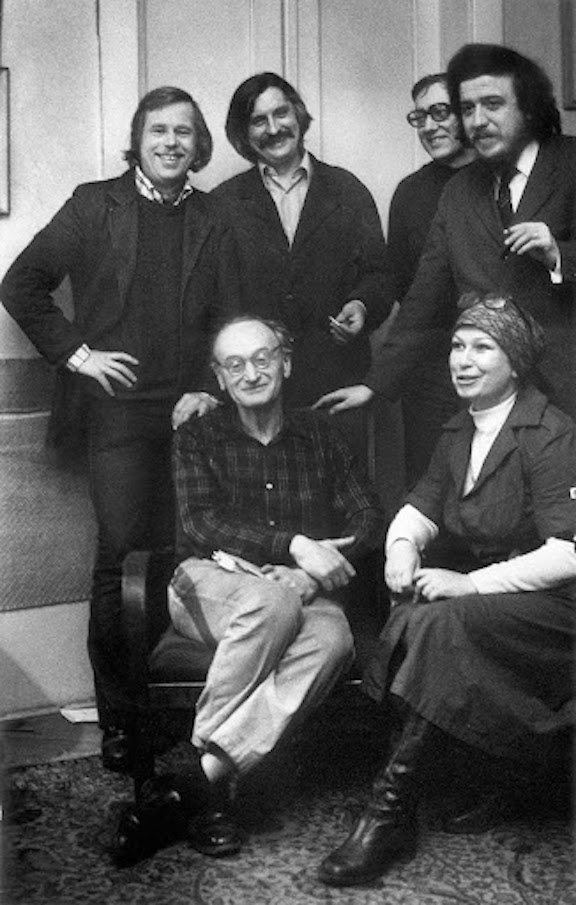

*Image: Charter 77 Czech dissident leaders in 1979. Standing (L-R): Václav Havel, Jiří Dienstbier, Ladislav Hejdánek, and Václav Benda; seated are Jiří Hájek and Zdena Tominová. [Photo by Ondrej Nemec]

You may also enjoy:

Brad Miner’s The Divine Plan: A Review

+Fr. Mark A. Pilon’s Time for Civil Resistance to Civil Aggression