American Catholics made a trade. You may not be aware of it or have personally participated in it. But it’s likely, if you’re a Catholic living in the United States in 2022 reading this, you feel its effects (and benefits). And though it may sound bleak, the trade more-or-less destroyed the American Catholic identity familiar to those living just a couple of generations ago.

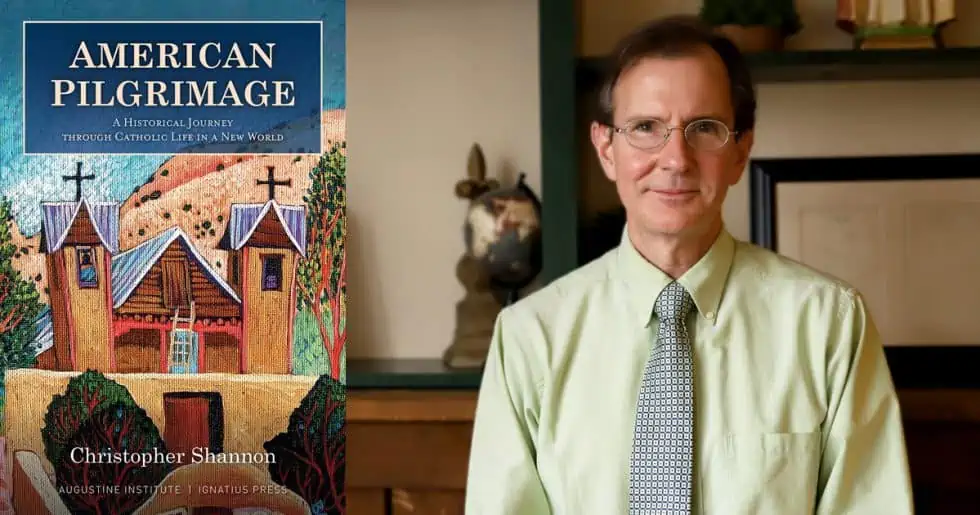

That’s perhaps the most salient lesson I derived from Christendom history professor Christopher Shannon’s new book, American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey Through Catholic Life in a New World. Though Shannon’s history covers much ground beyond just the United States, with long early chapters on Spain and France, the sections on England and the United States teach the most important lesson.

First, consider a few numbers. In 1969, when the U.S. population was about 202 million, there were about 60,000 diocesan priests. Today, with a national population of about 330 million, there are fewer than 40,000. And it’s not as if the number of Catholics here declined over that period. Far from it: we increased from about 30 million in 1950 to more than 70 million today (plus another 13 percent of American adults who describe themselves as “ex-Catholics”). The drop is even more stark for women religious: in 1970 there were about 161,000 women religious in the United States; today there are about 42,000.

What happened? According to Shannon’s incisive narrative, those numbers are emblematic of an epochal shift, in which Catholics, beginning in earnest in the mid-twentieth-century, traded their parochial, traditionalist, and often ethnic Catholic clannishness for the domesticity of bourgeois, suburban America. Catholics became just another “denomination” in big-tent American Judeo-Christianity – devout, patriotic, and trustworthy members of America’s civil religion.

How and why that happened is a complicated story beginning in the early years of the Republic, when Catholics like Baltimore archbishop John Carroll (1735-1815) aimed to synthesize “old World faith and New World culture,” as Shannon puts it. It continued through the nineteenth century with prominent Protestant converts to Catholicism, such as Orestes Brownson, who were critical of the insular and often unassimilated ethnic Catholics from Ireland, Germany, and elsewhere.

But it reached its most dramatic moment in presidential candidate John F. Kennedy’s address to the (Protestant) Houston Ministerial Association in 1960. It was there that our first Catholic president declared: “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute. . . .I believe in a president whose religious views are his own private affair.” Indeed, as Shannon notes: “Aside from attendance at the church of his choice on Sunday, Kennedy could have been any other upper-middle-class white American.”

Of course, Kennedy’s words represented a trend that was already decades old. It was visible in the departure of Catholics from their tight-knit urban parishes for the more anonymous, religiously diverse suburbs. Shannon explains: “The suburbs cut Catholics off from that world and placed them into a social setting where they mixed much more freely with non-Catholics.” And as long as our Catholicism was a private affair, non-Catholics didn’t care.

Suburbia also meant embracing a family life that often looked more Protestant than Catholic. As early as 1952, about half of Catholics had no moral qualms with artificial birth control. That translated to fewer kids for Catholics, who focused their energies on the same kinds of values as their Protestant neighbors: consumerism, physical and emotional fulfillment, and affluent professionalism. “Most Catholics had made their peace with artificial contraception and an increasing number seemed willing to accept legal abortion,” writes Shannon.

There were of course other relevant developments. The “Land O’Lakes Statement” of 1967 sought to modernize and assimilate Catholic academic institutions into the broader secular (or nominally Protestant) American academy. Catholic thinkers like John Courtney Murray, S.J., meanwhile sought to repudiate scholars such as Will Herberg and Paul Blanshard, who claimed that Catholicism and democracy were antithetical. Rather, Murray famously declared, the Founders “built better than they knew.”

Whether we are talking about social, economic, educational, or professional matters, the goal was always the same: develop the habits “required to attain a decent, moderate middle-class lifestyle.” And boy, did we succeed: most Catholics in post-World War II America secured middle-class status. We now comprise a significant percentage of both houses of Congress and a majority of the Supreme Court, and (at least nominally) occupy the White House.

Did we lose anything in the process? Shannon thinks so: “What has decidedly been lost is unity, or better, a sense of people-hood. Despite the rhetorical shift toward understanding the Church as the ‘people of God,’ there are few if any ways in which Catholics stand apart from other Americans to identify themselves as people.” There’s also the depressing fact that ex-Catholics make up the nation’s second-largest religious demographic. The more we tried to be like middle-class Protestants, the less we cared to be serious Catholics.

More radically, the recent secularized intellectual and cultural offshoots of Protestantism – progressivism, the sexual revolution (culminating in the LGBT+ orthodoxy), and racial activism – have imposed themselves on the American public, including Catholics.

In one of his most astute observations, Shannon notes: “Soon after Kennedy declared that his faith was a totally private matter, various strains of the counterculture rallied around the slogan ‘the personal is political.’” Catholics got bourgeois respectability, but we let the post-Protestant Left impose their anti-Christian ideologies on the American people, including millions of Catholic kids in the nation’s public schools. “Religious pluralism seemed to require a privatization of faith, or at least those aspects of the faith that set Catholics apart from the universally American.”

Perhaps this trade was in certain respects inevitable. Catholics weren’t going to live in ethnic ghettos forever. And however much we can be cynical about the materialist nature of the exchange, what parents don’t want their children to do better professionally and economically? The more urgent challenge, however, is ensuring they do spiritually better as well.

You may also enjoy:

David G. Bonagura Jr.’s Catholic Schools and the Woke Revolution

Brad Miner’s “Practicing” Catholics