There’s no shortage of conversations these days about men and masculinity. Everyone seems to be wondering: “What’s up with men?” From transgender debates, to the Me-Too movement, to concerns about the economic and marital prospects of young men (especially working-class men) and the political implications of their plight, our culture is saturated with questions having to do with masculinity. Lots of questions, lots of debate, but not a lot of answers.

There are those who treat masculinity as a mere construct, devoid of any essential content. The only purpose of masculinity – not an essential purpose, mind you, but a practical purpose – is to assert power in the interests of some oppressor class. The strong dominate the weak. The jocks bully the nerds in high school. Macho guys mistreat and condescend to women. You get the idea.

Then there are those who, often in defiance against the aforementioned claims of toxicity, assert masculinity as a collection of particular physical or psychological traits: physical strength, assertiveness, confidence, discipline, leadership, stoicism, dominance, competitiveness, and so on. Follow this line of thinking far enough, though, and the sum of the parts inevitably proves less than the whole. Masculinity-as-lifestyle-choice is no more interesting a subject than masculinity as a tool of patriarchal oppression.

To be fair, neither of these views is entirely mistaken. Men actually have taken advantage of certain strengths and social advantages to mistreat women. And there are certain traits and qualities that are and ought to be associated with masculinity – just as there are certain behaviors and qualities which are decidedly “unmanly.”

Now, like most men I know (at least those I consider good examples of what it means to be men), I don’t actually spend very much time thinking about what it means to be “manly” or worrying about masculinity. The truth is, I generally find discussions about masculinity to be somewhat tedious and overwrought.

As it happens, I was invited last month to speak to a group of university students – mostly young men – on the topic of “healthy masculinity.” So, I took a break from my long-standing habit of not thinking about “healthy masculinity,” to consider what nuggets of wisdom or insight I might be able to offer these young men. I came up with three points.

First: As far as I can tell, after a lot of thought, healthy masculinity is just what happens when a man lives virtuously. That’s it. A virtuous man, by the fact of being virtuous, lives his masculinity in a healthy way. (I mean, it’s right there in the root of the word “virtue,” from the Latin virtus, which refers to those qualities proper to a vir, a man.)

This might sound overly simplistic, even circular, but it isn’t. Notice that the converse is not always true. Not everyone who strives for “healthy masculinity” as a goal will live virtuously. If we want healthy masculinity, aim to teach young men virtue: the rest will take care of itself. But if we tell young men they must exhibit “healthy masculinity” and then fail to instruct them in real virtue, we’re setting them up for confusion and failure.

Second: Fatherhood makes the man. There’s no worthwhile conception of masculinity which does not have fatherhood as its primary reference. Obviously, not all men live their fatherhood in a biological capacity. But all men, without exception, are made for fatherhood. I know celibate priests who are tremendous fathers. I know married men without children of their own, or with adopted children, who are tremendous fathers. It is for good reason that St. Joseph is the patron of fathers.

Whatever physical or moral strength is in a man, it is his so that he might be of better service to those entrusted to his care. This is demonstrated starkly in the breach: there is nothing less manly, nothing more utterly antithetical to fatherhood, than a man who takes advantage of, abuses, or mistreats women and children.

Third point: Fatherhood is a terminal condition. Like all true vocations, fatherhood finds its fulfillment in paying out one’s life in service to others. A father loves unconditionally, even as he knows that he will diminish as his children increase and grow. But fatherhood is about more than self-sacrifice.

Most of us learn about fatherhood first from our own fathers. As children, we learn our fathers are invincible, omniscient, omnipotent, awesome, all-loving. (No one Mom looks at the way she looks at Dad could be anything less!) As we get older, we learn better. We grow out of this view of our fathers. We learn that our fathers are – we hope – very good men, they’re still just ordinary men. Fallible, flawed, mortal.

Then as men (I’m speaking here to the men), we become fathers ourselves, and the view of fatherhood shifts again. If my Dad wasn’t perfect, Lord knows neither am I! But my own little child doesn’t know that. Not yet.

And then it begins to sink in. That first childish image of Fatherhood – invincible, omniscient, omnipotent, awesome, all-loving – that’s real Fatherhood. I may be a dim, poor reflection of it. But that doesn’t mean it’s not real. There really is a Father like that. I’ve known that love. More amazingly, despite all my inadequacies, imperfections, and selfishness, He’s allowed me to taste just a hint of what it is to love the way He does. And He’s allowed me, called me, to show a glimpse of that love to my own children. It’s humbling, and not a little terrifying.

That’s what I mean by Fatherhood is a terminal condition. Fatherhood is not just “unto death.” It’s aimed at something; it’s headed somewhere. It points to Someone who isn’t me. It’s an unmerited chance to participate in the love of God the Father. A chance to be, for someone else, a glass through which, however darkly, they can glimpse Him. It’s humbling and not a little terrifying, and wondrous beyond measure.

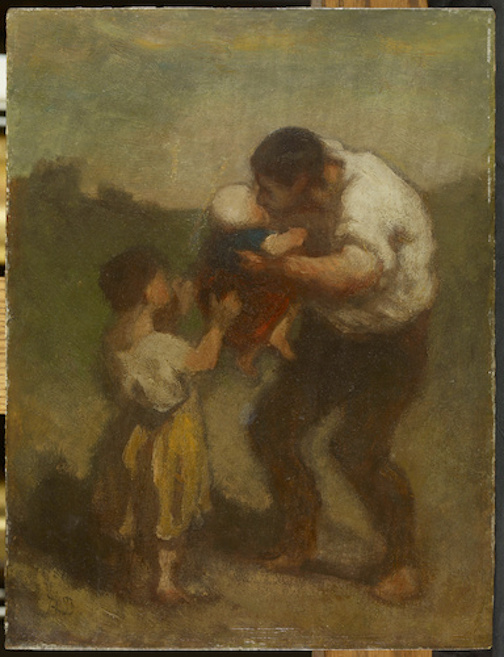

*Image: The Kiss (Le Baiser) by Honoré Daumier, c. 1845 [Musée d’Orsay]

You may also enjoy:

Michael Pakaluk’s The Gospels Begin with Sex

Taynia-Renee Laframboise’s Miner’s “The Compleat Gentleman”