Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini

Robert Royal

We expected, because of his advanced age and notices from the Vatican, that Benedict XVI was near his entry into eternity. But as always happens when someone dies – let alone a beloved teacher, scholar, pastor, and pope – when the day actually comes, it’s still a shock. And changes things forever.

Joseph Ratzinger made such large contributions to the Church and the world that his name and his legacy will now enter into the great cultural heritage of the Catholic faith, permanent matter for reflection about numerous things, human and divine.

There were large public moments in his life that made an enormous difference to recent decades. He was accused in some quarters, for example, of having been a progressive at Vatican II, but having “gone over to the Dark Side” during the student protests of the 1960s. A serious examination of the facts (e.g., Peter Seewald’s Benedict XVI: A Life) shows that this is simply mistaken.

Ratzinger’s thought moved quietly, calmly, consistently at a depth that was not fundamentally changed by social turmoil. His great steadiness alone was a valued point of reference that will be sorely missed.

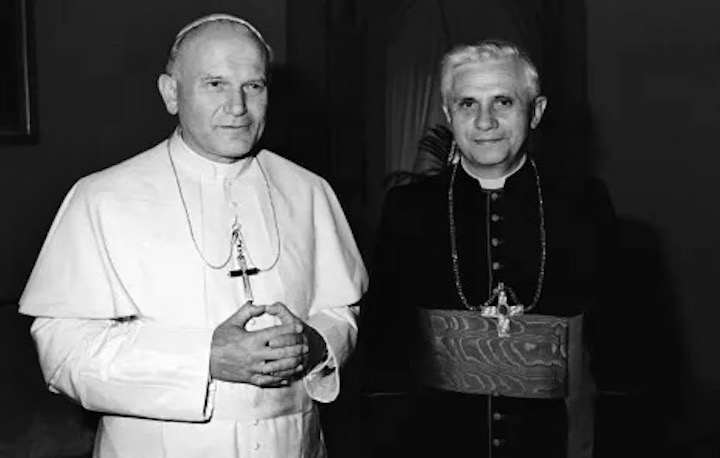

His radical students respected – and praised – him for that, even as he came to recognize the limits of “dialogue” with a certain type of radical in the academy, Church, and larger world. It was an insight that served him well when as a bishop and then head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith he had to confront dissidents, movements like liberation theology, and what he would later call “the [Second Vatican] Council of the media,” which was far different than the one he and the young Karol Wojtyla had helped to shape.

For me, one personal encounter summed up much of his life and thought. I was asked to write a history of the Swiss Guard for their 500th anniversary and gave him a copy of The Pope’s Army, on May 6, 2006. There was a crowd around us, but he took the book between his hands, almost caressing it the way a book-lover does, began paging through it looking at particular chapters, and said, “This is wonderful, now I can read about these guards that protect me.”

By the way, though we still need to know more about his resignation, the Swiss Guards told me at the time that, among other things, he was physically exhausted to an extent painful to see.

I’ve always thought that taking the name Benedict – one among sixteen of that name – was a sign of many things he believed about his whole life. Benedictus, “blessed” to be sure, to have been born who and where he was, and over a long life. Benedictus, in the sense of continuity with Benedict XV, who almost a century earlier dealt with World War I and its aftermath throughout the globe. But finally Benedictus, even as pope, because – in spite of great learning – just a simple Christian in the long line stretching back to Jesus Himself.

__________

Robert Royal is editor-in-chief of The Catholic Thing and president of the Faith & Reason Institute in Washington, D.C. His most recent books are Columbus and the Crisis of the West and A Deeper Vision: The Catholic Intellectual Tradition in the Twentieth Century.

The Mozart of Theology

David G. Bonagura, Jr.

Many will want to declare Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI a “Doctor of the Church,” meaning a holy teacher who has made a unique contribution to our understanding of God. Ratzinger blazed new trails in the fields of revelation, faith, Christology, and liturgy, and united them all through a single thread: the God who reveals Himself is the Word, the Logos, who makes His dwelling among us so we may have life in Him, and so we may worship Him in spirit and truth. Ratzinger may rightly be called, in a mix of Latin and Greek, the “Doctor Logou” – “The Doctor of the Logos.”

Ratzinger’s theology was more than deep thoughts for nerds in the field. It was soul-stirring. Over many decades this pious teacher inspired countless believers and converts by directly addressing modernity’s challenges to faith, culture, and the Church. Like a skilled medical doctor, he issued incisive diagnoses and offered potent remedies. Ratzinger is a doctor of the Church because he was a doctor for the Church limping after her post-Vatican II collapse. He provided healing and hope for the faithful who desperately needed a heroic, clear-minded doctor not only to heal, but to lead.

With honest candor about the Church’s difficulties, Ratzinger breathed life into the faithful beleaguered by an apparently collapsing Church. As early as 1981 he published a collection of essays, The Feast of Faith, that criticized aspects of the Missal of Paul VI, which “was published as if it were a book put together by professors, not a phase in a continual growth process.” In 1985, his frank criticisms of Vatican II’s implementation were published as The Ratzinger Report. His criticisms came from a deep love of the Church and a hope that she could still reap good fruits from the Council.

What made Ratzinger so unique was his ability to penetrate deeply into the problems of Modernity and to present God cogently as the answer to our current ills. His first foray here was the groundbreaking 1968 Introduction to Christianity, where he argued that “Christian faith lives on the discovery that not only is there such a thing as objective meaning but that this meaning knows me and loves me, that I can entrust myself to it.”

In later years Ratzinger’s speeches and essays continued in this vein, eventually published as Truth and Tolerance, Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures, Without Roots, and Dialectics of Secularization. Through these works Ratzinger demonstrated how post-Vatican II dialogue was supposed to function: “we must be committed to promoting the evangelization of cultures, conscious that Christ himself is the truth for every man and woman, and for all human history.” In his famous 2005 pre-conclave homily Ratzinger synthesized this work in a manner worthy of his nickname “the Mozart of Theology.”

For Ratzinger, this “adult” faith found its full expression in the liturgy. In his magnum opus, The Spirit of the Liturgy, he explains how logike latreia – “divine worship in accordance with logos” – is expressed in the Eucharistic sacrifice, which is the “means to enter into the openness of a glorification of God that embraces both heaven and earth.”

Throughout salvation history, God has raised up prophets, teachers, and saints to lead His people through the crises of a given moment. Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI was all of these for a wounded Church seeking direction amidst the onslaught of 20th and 21st centuries’ anti-God ideologies. Doctor Ratzinger healed by offering the medicine of divine truth to an age imprisoned by its denial of truth. May he receive the reward of the faithful laborer in the Lord’s vineyard.

__________

David G. Bonagura, Jr. teaches at St. Joseph’s Seminary, New York. He is the author of Steadfast in Faith: Catholicism and the Challenges of Secularism and Staying with the Catholic Church: Trusting God’s Plan of Salvation.

The Greatest Scholar of My Lifetime

Anthony Esolen

I thank God for the life and the work of Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, the greatest Catholic scholar of my lifetime, a man deeply learned not only in theology and philosophy, but in arts and letters– and the history of mankind. The true theologian is he who prays, and Pope Benedict was a man of constant prayer, who did what he could to make it more likely that the members of his flock would pray – would have the opportunity, and would benefit from the encouragement, to enter into the heart of prayer.

All that he ever wrote or said about the Mass, it seems to me, was prompted by his profound devotion to that consummate prayer, and his care to guard it against what would derogate from it, dull it, or deform it so that it would be rather an arena for merely human performance and its arbitrary and shifting tastes.

I have profited much by his works, especially Jesus of Nazareth, but I shall always remember the message that an alarmed atheist friend sent me after Benedict’s now-famous speech at Regensburg: “What is Benedict thinking?” My friend was alarmed because he did not understand what the pope was saying, and how could he, from the foolish reports that were flying about, accusing the pope of bigotry against Islam?

The pope stood as what I called the last true liberal in Europe, defending what Maritain called “the range of reason,” not limiting it to empirical tests and measurements, or to the windswept deserts of abstract logic, but declaring its power to reveal moral truths, to speak to every feature of a human life. Thus did the voluntarist Islamic scholar in his conversation with the Christian emperor Michael Paleologus have more in common with western secularists than he or they had in common with the great traditions, both eastern and western, that see reason as a beacon to illuminate what is good, true, and beautiful.

Benedict was thus issuing an invitation, a plea. And every time he was called on to defend Catholic teaching, he did so because he understood that failure would be like shutting a door in the faces of those who seek the truth. He was not “God’s rottweiler.” He was never currish, as his critics were. He never spoke evil of others, as they often spoke evil of him.

Perhaps it is a mark of the Church’s divine origin that almost everything people have said about the last several popes has been the direct opposite of the truth. Paul VI was not a hide-bound moral conservative, but a rather timid liberal who, when the crisis came, would not betray the truth. John Paul II was not an authoritarian, but a kindly and lenient man whom wicked and deceitful churchmen took terrible advantage of, while slandering him, as spoiled children will.

Benedict was not surly, but eminently charitable to his opponents, and, like Thomas Aquinas, he would state their case better than they themselves could do, though they never took the trouble to engage him in true scholarly debate. I think they knew better than to dare to try it.

In Paradisum deducant eum angeli.

__________

Anthony Esolen is a lecturer, translator, and writer. Among his recent books are Nostalgia: Going Home in a Homeless World, and most recently, The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord. His new website isWord and Song.

Quiet Manliness – and Courage

William Edmund Fahey

Heu mihi, Domine, quia incolatus meus prolongatus est.

“Woe is me, O Lord, that my sojourn is prolonged.”

That second antiphon from the Office of the Dead struck me as I was praying for the soul of Pope Benedict XVI. It was not Vespers when I heard of his death, but it felt like Vespers – the end of a day, a year, an age; and I was casting about for prayers that I could speak, and which more so could speak for me.

The psalm (119) concludes: “My soul hath been long a sojourner; with them that hated peace I was peaceable: when I spoke to them they fought against me without cause.” I dread looking at the news reports, many of which will no doubt be marked by an emphasis on Benedict’s “combativeness.” Yet it was never Benedict who was belligerent, but those who did not wish to speak with him. And they didn’t wish to speak for they were concentrating on victory and power, rather than truth.

As I grow older, my perspective on death and dying is changing. This is a natural and a supernatural grace. “Woe is me, O Lord, that my sojourn is prolonged.” I am glad that the Church places this upon our lips, for it is in our hearts: there is a certain weariness that comes even amongst the best of temporal things.

Yes, the Office of the Dead opens with the antiphon, “I will walk before the Lord in the land of the living.” That verse is said in hope, just as we say at Lauds in the Office of the Dead, “Let my humbled bones again rejoice to the Lord.” We hope for that renewed life. But we know the feel of humbled bones worn in this passage. This world demands arduous training for the arduous good before us, and the Church is kind in permitting us honest words about our condition while on our pilgrimage.

I am not a papal historian nor a theologian. I look forward to reading their summaries and tributes. Yet I admire and shall revere the memory of Benedict for a simple reason: He was a man.

John Paul II is in part remembered for his very visible manliness – his skiing, hiking; his great and genuine physicality. But Benedict’s manliness and courage moved me more deeply. His was the courage of a quiet man, a teacher, who like all true teachers preferred conversation in the slanting light of a seminar room, filled with engaging minds and engaging books, to the glitter of public life.

He had to forsake that quiet for the good of others. He did so, as a man does so. Like so many of the Church’s greatest scholars and teachers, his life was saddled with administrative work, which he carried well. My tribe revels in the false image of detached leisure and often forgets that Augustine, Gregory, Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, More, Newman, and just about every deep mind of our Catholic civilization, were beset by uncomfortable travel, nagging administration, and the unwelcome diplomacy that faces those who must manage something larger than their desks.

Only a man wearied in noble action deserves the words “eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord.” And only a man like Benedict, who forsook for so many hours the gentle slanting light of his study, can receive in its fullness that “perpetual light” which God reserves for his servants.

__________

William Edmund Fahey is a Fellow at Thomas More College, where he also serves as its third president.

I Wish He Hadn’t Resigned

Brad Miner

I believe Benedict XVI’s resignation has done damage to the Church.

Keeping in mind Our Lord’s promise that the gates of hell shall not prevail, we cannot now know the extent to which the current crisis in the Church will worsen.

Of the greatness of Joseph Ratzinger there can be no doubt. His election to the papacy following the death of St. John Paul II seemed miraculous and is why his resignation after just eight years is as regrettable as it was shocking.

We can only speculate how things might be in the Church today had Benedict held on until death, which is what popes have always done, Celestine V and Gregory XII notwithstanding.

Of course, Joseph Ratzinger was primarily an academic – among the greatest theologians of the last century. But he had also been an able administrator during his near quarter-century as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. It’s part of what made him a solid choice for the 2005 conclave.

He represented continuity and competence.

I do not know why Benedict resigned. Various reasons have been given, which in the end suggest he found the papacy too arduous. As Rod Dreher wrote the other day, “we honestly can’t say what mysterious providence was at work in this Great Refusal.”

But I wish he would have delegated some of the work that needed to be done in the Vatican.

Surely, there are men highly capable of executing necessary reforms, some of which Pope Francis has addressed, and all of which the then 85-year-old Benedict could have handled with trusted advisors.

He’d been resident in the Vatican for more than two decades prior to his election as pope, so he must have had some sense of who there was depraved and who moral. I shouldn’t name names because I don’t know many of them, but I’m certain that for every Paglia or Becciu there was a Pell and a Burke. The balance overall may tip in the wrong direction, but surely there were enough “good guys” to allow Pope Benedict to continue steering the Barque of Peter on its true course.

And the fact that his predecessor crisscrossed the globe didn’t mean Benedict had to.

All this being the case, I can only add (with love): “His lord said to him, Well done, good and faithful servant; you were faithful over a few things, I will make you ruler over many things. Enter into the joy of your lord.” (Matthew 25:21)

__________

Brad Miner is the Senior Editor of The Catholic Thing and a Senior Fellow of the Faith & Reason Institute. His The Compleat Gentleman is now available in a third, revised edition from Regnery Gateway and is also available in an Audible audio edition.

A Reluctant, Consequential Pope

Fr. Gerald E. Murray

Benedict XVI’s almost eight-year pontificate was consequential in many ways. He was a natural successor to his close friend John Paull II. He fulfilled expectations that he would foster and advance JPII’s efforts to revitalize and strengthen the Church, which had been wounded by misguided attempts to turn the Second Vatican Council into a blueprint for a Brave New Church in which just about everything would be up for grabs. Benedict promoted the idea of the “hermeneutic of continuity”; Vatican II was to be understood and implemented in complete harmony with the rest of Church history and teaching.

One of his most important acts was to attempt to put to rest the post-Conciliar liturgical conflicts. Benedict’s decision to grant greater freedom for the celebration of the traditional Latin Mass was the fruit of his love for the form of the sacred liturgy that he had experienced in his parish church as a boy, and of his heartfelt desire to reconcile the followers of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. He rejected the arguments of those who saw appreciation for the Church’s ancient rites as mere nostalgia or as stubbornness born of a fear of change.

Among many other things, Benedict will be remembered for writing: “

What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful. It behooves all of us to preserve the riches which have developed in the Church’s faith and prayer, and to give them their proper place.

His most consequential decision was to step down from the Throne of Peter in February 2013. The weight of the papal office upon his shoulders was heavy indeed, made even more onerous by the various intrigues and crises in the Roman Curia. Acutely aware of the massive problems in the Curia, he did not see himself as capable at age 85 of cleaning house. Benedict was first and foremost a theology professor. Not many professors want to become the college president, and even fewer possess the gifts and stamina required in such a job.

Benedict was a reluctant pope who acceded to his election in 2005 as an act of obedience to the will of God expressed by the vote of the cardinals. Yet he never made the necessary full plunge into reforming and redirecting the Roman Curia. His resignation was an understandable decision to take up at last his long-desired retirement from responsibility for administering the affairs of the Church. He wanted to prayerfully read, study, contemplate and write. That was his lifelong passion, which he saw as his most effective way of serving the Lord.

The greatest legacies of Joseph Ratzinger are his magnificent theological and spiritual writings, the fruit of his exemplary faith and devotion to Christ. For this we are most grateful, even as we speculate on what might have been if he had remained at the helm of the Barque of Peter.

__________

The Rev. Gerald E. Murray, J.C.D. is a canon lawyer and the pastor of Holy Family Church in New York City. His new book (with Diane Montagna), Calming the Storm: Navigating the Crises Facing the Catholic Church and Society, is now available.

Have We Stopped Listening?

Michael Pakaluk

Near the end of his great treatise, Principles of Catholic Theology, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger discussed the Second Vatican Council ten years after. Was it worth the crises, the trials, the misunderstandings and misconstructions, the confusions?

He refers to a comparison offered at the time by Karl Rahner: “huge amounts of pitchblende are needed to produce a small quantity of radium, which is the sole object of the process. In like manner, he said, the tremendous exertion of the Council was, in the last analysis, worthwhile because of the small increase in faith, hope, and love.” The future Pope Benedict XVI loved these precious virtues as much as anyone. But he rejected the comparison because, unlike a process of chemical refinement, there is no guarantee in this case that there will even be “radium” to discover. “The crucial question is whether there are individuals – saints – who, by their personal willingness, which cannot be forced, are ready to effect something new and living.” But that’s you and me, right?

The word in Rome used to be, “People came to see John Paul II, but they come to listen to Benedict.” Have we stopped listening? Pope Benedict was always about breaking open the dynamism of the Eucharist so that it would transform us. Discovering the good news that to exist is good, and that God is good and redeems his Creation – and letting ourselves live in the joy of that discovery. Finding as many ways to be saints as there are different human beings. Celebrating our new life in the Holy Spirit in the communio of the new ecclesiastical movements, associations, and personal prelatures.

Again, have we stopped listening? As I look back over my life, perhaps remembering when he became pope, have I taken real steps since that time to become one of those saints? This is how we would show gratitude for him. And maybe if we overlooked his teachings then, it is propitious to “listen” to them now: his catechetical addresses, encyclicals, and books.

There is tremendous equanimity in that last chapter of Principles. Most councils are followed by long periods of tremendous crisis, he says. It is only over the very long term (for those councils which are not forgotten) that we may see with settled clarity their fruitfulness and even necessity.

And then he closes with a startling comparison: of a Christian in today’s world to Don Quixote: like him, “we started out boldly and full of confidence in ourselves,” but “gradually we have become aware that behind the closed doors are concealed those things that we must not lose if we do not want to lose our souls as well. Certainly we cannot return to the past, nor have we any desire to do so. But we must be ready to reflect anew on that which, in the lapse of time, has remained the one constant. To seek it without distraction and to dare to accept, with joyful heart and without diminution, the foolishness of truth — this, I think, is the task for today and for tomorrow.”

__________

Michael Pakaluk is a professor in the Busch School of Business at the Catholic University of America. His new book, Mary’s Voice in the Gospel of John: A New Translation with Commentary, is now available. Prof. Pakaluk was appointed to the Pontifical Academy of St Thomas Aquinas by Pope Benedict XVI.

Joseph Aloysius Ratzinger

David Warren

Benedict XVI was still “sustaining the Church,” in the words of his successor, when the word came from Rome that he was dying. This frail and aged prince, charged by God to give strength to the faithful and lead them in the way, has now ceased this life of silent prayer on Earth. We who were sustained by him are, for the moment, lost; sent back again to Christ, crucified and risen. Ratzinger’s learning and wisdom are now added to the remembrance of the popes over the centuries; he built upon the splendor of Catholic teaching. His gentle voice has been added to that accumulation.

He has left an incomparable record in his writings, in many volumes of close reasoning and holy, patient inspiration. He was the pope whose task was to continue the mission of Saint John Paul II, confirming the worth in Vatican II while bringing its convulsions to a conclusion. His brilliant liturgical innovations showed how this could be done, and in time the Church will return to them. But he had an impossible task, that no human could achieve by an act of ecclesiastical legislation. He pointed the way, however, and showed the attitude that could win through.

Pope Benedict faced down, to the limits of his capacity, the corruption in the Church that had grown with late modernity. Once again, he could not categorically succeed, but gave hope to the well-meaning.

I loved the soft, dry humor with which he communicated his limitations and possibilities. It was a part of the graciousness with which he accepted the human qualities in those all around him. “When I make a pronouncement, and there is no criticism, I must examine my conscience,” he once said, ironically not joking. This was the great, reliable assistant to John Paul, who was actually well prepared to follow him in the papacy – yet at the personal cost of abandoning the life of monastic retirement for which he obviously longed.

I loved him in my penitence, knowing there was no restriction in his kindness; that his ambitions for the Church were not ambitions of his own.

_________

David Warren is a former editor of the Idler magazine and columnist in Canadian newspapers. He has extensive experience in the Near and Far East. His blog, Essays in Idleness, is now to be found at: davidwarrenonline.com.

In Appreciation

Thomas G. Weinandy, OFM, Cap.

What I appreciated most about Pope Benedict XVI, a virtue that he manifested throughout his life, was his quiet humility. He was never a boisterous man who pushed himself into the limelight. Rather, his calm, unassuming presence brought to every situation a reassuring strength that all would be done well and in accordance with the Holy Spirit’s will. This humility was founded, not upon Benedict’s intellectual acumen, but upon his firmness of faith in the Gospel, a faith that was expressed in the Church’s magisterial teaching and her ecclesial theological tradition. Benedict was but a humble servant of Jesus Christ, his Lord and Savior.

That said, all would acknowledge, and most would praise, Benedict’s intellectual ability, a gift that is seen in academic work. To this day, his Introduction to Christianity continues to be read by appreciative students and members of the theological academy. Likewise, his Spirit of the Liturgy is a foundational text for appreciating and understanding the Church’s liturgy that has come down to us through the ages. Every priest and seminarian should be required to read and study this work. It would help alleviate much of the rancor that exists in our present “liturgical wars.” His sound learning and wise counsel would calmly prevail.

Both before and after his election as pope, Joseph Ratzinger bore the slings and arrows that were hurled at him by many within and outside the Church. Members of the secular and ecclesial liberal elite media were, and still are, relentless in their criticism and in their characterization of him as an unyielding, “rigid” conservative. Such rancor towards Benedict, however, merely makes evident the lack of faith among many of his critics, as well as simultaneously highlighting his own steadfastness in the faith.

Benedict, as a person, as an academic, as an archbishop, and as the pope was and remains a light in the darkness of our present world. His light will continue to shine even now when he has passed from this world into his heavenly reward. There, with all of the Saints, he will give glory to God the Father, in union with Jesus, the risen incarnate Son, in communion with the love of the Holy Spirit.

__________

Thomas G. Weinandy, OFM, a prolific writer and one of the most prominent living theologians, is a former member of the Vatican’s International Theological Commission. His newest book is the third volume of Jesus Becoming Jesus: A Theological Interpretation of the Gospel of John: The Book of Glory and the Passion and Resurrection Narratives.