This month marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of a great modern Catholic genius. Like many such geniuses, he and his legacy have been all but forgotten. But Charles Péguy will return – for some of us he never left – because his words and the witness of his life offer a vitally original perspective on the modern Church and the contemporary world: a perspective that, paradoxically, also becomes more and more relevant – and perhaps a way out of our accelerating crises – with each passing day.

Long before the term “political correctness” became a media shibboleth, for instance, Péguy noted how certain attitudes were becoming obligatory at political demonstrations: “If you don’t take that line you don’t look sufficiently progressive. . .and it will never be known what acts of cowardice have been motivated by the fear of looking insufficiently progressive.”

Coming from a young socialist – until he experienced being “canceled” (avant la lettre) by the party’s nomenklatura – this reflects the unwavering honesty and decency of a man who refused to lie just because it reflected badly on his own party. He paid the price: poverty (a heavy burden for someone with a wife and four children) and marginalization by former friends.

This all occurred over the closing of Catholic schools and monasteries by the anti-Catholic French President Émile Combes, in theory because of the Church’s role in the Dreyfus Affair. Péguy was not a Catholic at the time, but it was simply clear to him that the injustice against Dreyfus (a false charge of treason) didn’t justify another injustice – against Catholics.

His most famous words are particularly relevant to our current situation: “Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.” (Tout commence en mystique et finit en politique.) What he meant is that every powerful movement begins as a spiritual force, and then is “incarnated” in concrete action. This already reveals a rare depth of heart, especially in public affairs: the France of Péguy’s day was divided, much as we are, between conservatives and progressives. But he recognized related ideals – mystiques – in the best republicans and Catholics.

Few know the warning, however, that immediately follows: “The interest, the question, the essential is that in each order, in each system, the mysticism not be devoured by the politics to which it gave birth.” Many politicians privately mock this sort of idealism – either regarding it as impractical or using it for personal or partisan purposes. But, says Péguy, it’s the mystique that provides whatever real life there may be in public affairs. And it’s the mystique that’s really practical, that gets something done.

Public life becomes fruitless – and sterile – owing to the practical atheism of all the parties, “the world of those who have no mysticism and boast of it.” In that perspective, the two camps suffer from the same disease: “The movement for de-republicanizing France is profoundly the same movement as the movement which de-Christianized her.”

It took some time to arrive on our shores, but it’s clear that in America, too, we’ve reached a point where the abandoning of our religious traditions threatens our political order, and vice versa.

But Péguy’s work extends far beyond politics. He’s a sort of French Chesterton, throwing off lines of great penetration seemingly without effort:

- Kantianism has clean hands because it has no hands.

- Tyranny is always better organized than freedom.

- Homer is still new this morning, and nothing perhaps is as old as today’s newspaper.

Like Chesterton, there’s also humor – more French wit than English belly laughs – and great vision not only in these sharp observations but in his (occasionally) massive books.

He’s a poet, of an eccentric kind, for instance, who wrote three “mysteries” – something between poetic dramas and verse monologues. The second, which is “about” the virtue of Hope (which he portrays as an eager child), opens with God Himself speaking:

The faith that I love best, says God, is hope.

Faith doesn’t surprise me.

It’s not surprising

I am so resplendent in my creation. . . .

That in order really not to see me these poor people would have to be blind.

Charity says God, that doesn’t surprise me.

It’s not surprising.

These poor creatures are so miserable that unless they had a heart of stone, how could they not have love for one another.

How could they not love their brothers.

How could they not take the bread from their own mouth, their daily bread, in order to give it to the unhappy children who pass by.

And my son had such love for them. . . .

But hope, says God, that is something that surprises me.

Even me.

That is surprising.

That these poor children see how things are going and believe that tomorrow things will go better.

That they see how things are going today and believe that they will go better tomorrow morning.

That is surprising and it’s by far the greatest marvel of our grace.

And I’m surprised by it myself.

And my grace must indeed be an incredible force.

This joking and ironic Deity, who speaks at times like a French peasant (Péguy grew up among such people), might quickly become tiresome. But he brings everything off beautifully in this and many other longer works. (Cluny Media has republished some of the key texts in handsome new editions.)

A key term to understanding Péguy is fidèle, faithful. He always claimed that he had become Catholic not by rejecting his earlier life as an idealistic young socialist, but by a faithful deepening and broadening of his initial commitments until, during an illness, he found himself a Catholic. He was part of the French Catholic literary revival that paralleled the one in England that gave us Chesterton, Belloc, Waugh, Greene, Spark, and many others.

The world is currently obsessed – and stunted – by staring at superficialities on screens. We owe it to ourselves to take a deeper dive into rich predecessors like Péguy who have much to teach that today we’re sorely lacking.

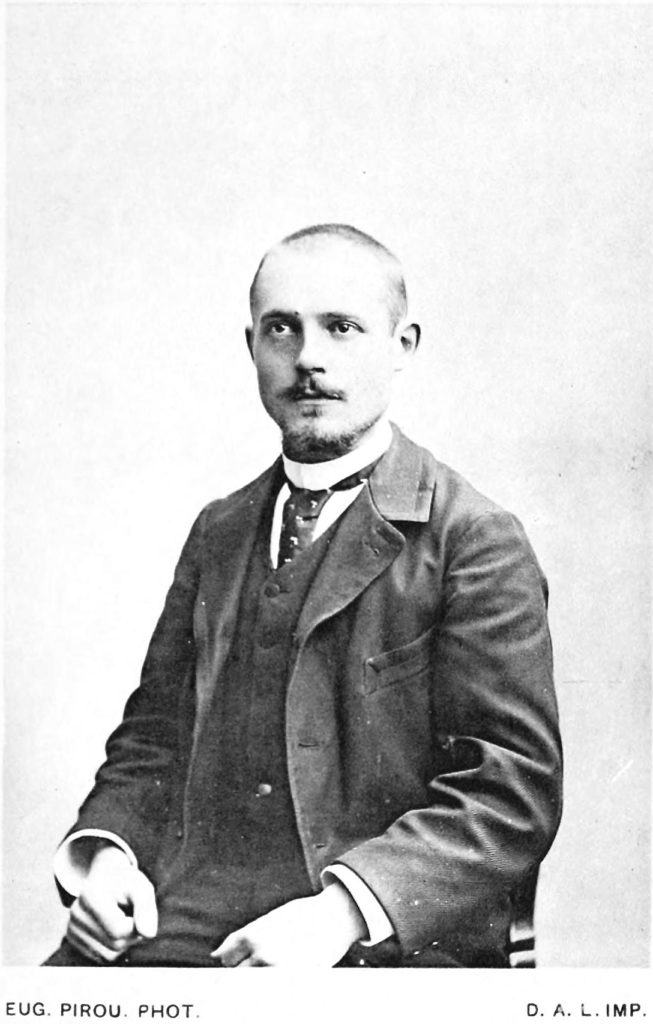

*Image: Charles Péguy by Eugène Pirou, c. 1910

You may also enjoy:

Francis X. Maier’s Memory and Gratitude

Charles Péguy’s The work of salvation [– from “Freedom”]