The Turkish writer Evliya Çelebi, visiting Vienna in 1665 on a mission for the Ottoman sultan, recorded “a most extraordinary spectacle.” The Habsburg emperor, when riding in the street, would pause his horse to let a woman pass. If he met a woman while on foot, he would greet her “in a posture of politeness.” He would then remove his hat “to show respect for the woman.” Çelebi concluded that “in this country, and in general in the lands of the unbelievers, women have the main say. They are honored and respected out of love for Mother Mary.”

It’s a telling, if incomplete, observation. Çelebi was right about the role of Christ’s mother in the Christian imagination and Mary’s influence on the development of Western thought and culture. By comparison, the status of women in Islam has always been, and remains, inferior. But in Christian Europe too, women typically had a dependent status. High-born women could, and often did, exercise great political and cultural influence. But they did so (almost) always, indirectly, through their men, who held formal authority in family and society. Husbands could revere, ignore, or mistreat their wives. . .with little recourse for the woman.

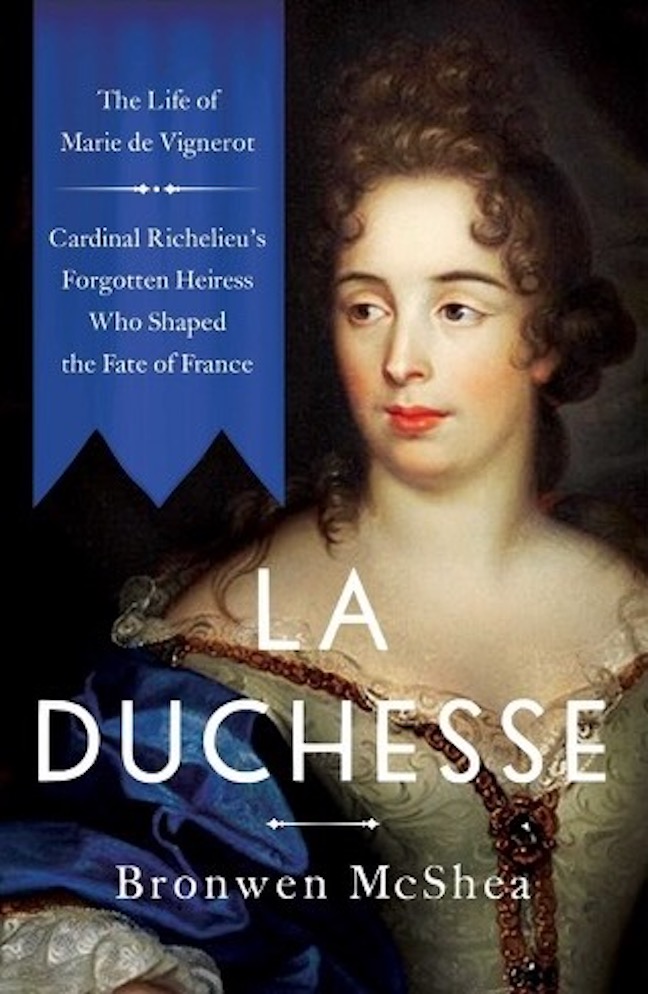

And of course, men also wrote the histories, excluding many women who might otherwise shape the narrative. This is what makes Bronwen McShea’s new book, La Duchesse, so absorbing. It captures with vivid grace and detail the life of one of the most important, if unheralded, women in French history.

Marie Madeleine de Vignerot was born in 1604 to a French aristocratic family of rural, relatively modest means. As with Thomas More and his beloved daughter Meg, Marie’s parents – unlike others at the time – insisted on a good education for their daughter.

At age 11, on the death of her mother, and with her father absorbed in the family’s difficult financial affairs, Marie relocated to her maternal grandmother’s home at Richelieu in the Loire Valley. There, and throughout her childhood, three of her closest relatives were clergymen. Among them was her young “Uncle Armand.” Armand had been training as a soldier, but when his older brother renounced his aristocratic right to a bishopric and retired to a monastery, Armand was ordained and named bishop of Luçon. This would change the course of Marie’s life.

A shrewd, intelligent man, as well as a sincerely devout one, Armand would rise quickly and eventually become the powerful “Cardinal Richelieu” known to history as First Minister of France. Marie, on the other hand, was married off at age 16 in a loveless but politically promising marriage to a man seven years her senior. When her husband died in combat two years later, and her father shortly thereafter, Uncle Armand – now Cardinal Richelieu – became her legal guardian.

As family, Marie enjoyed an early measure of her uncle’s trust. But over time, in Richelieu’s own words, she became the only person he fully trusted and loved, serving until his death as his closest aide and confidante, with access to his most sensitive political and ecclesial efforts.

With Richelieu’s support, Marie was named a duchess in her own right (as opposed to meriting the title through a husband) and a “Peer of France” – the only female in a select circle of senior nobility closest to the king. After Richelieu’s death, Marie vigorously defended his legacy, while extending her own extraordinary network of influence.

McShea’s lucid style and skillful research bring Marie’s historical period and its characters luminously alive. In Alexander Dumas’s great novel The Three Musketeers, Cardinal Richelieu is portrayed as a scheming political spider. In reality, while he could often be ruthless, he was also melancholic, prone to depression and migraines, merciful to those he respected, and profoundly religious.

The French Church resisted the Council of Trent’s reforms well into the 17th century, especially as they pertained to seminaries and the proper training of clergy. From his earliest days as a bishop until his death, Richelieu was the opposite. He energetically supported Trent’s reforms and worked tirelessly for the purification and renewal of French Catholic life. . .which included a firm hand against a growing French Huguenot Protestantism.

As for Marie, while she faithfully served her uncle, she was far more than his mere appendage. It’s unlikely the Cardinal could have achieved what he did without her aid. In her youth, she was a striking woman. She had a gifted intellect, a formidable character, and a lively interest in literature and the arts. She became a generous patroness of writers and artists, and an adroit builder of socially and politically influential networks.

She was appointed governor of the region of Le Havre, a position unheard of for a woman, which she stoutly defended from jealous male courtiers. She was also familiar with grief. In addition to losing a mother, husband, father, and uncle, she was childless and never remarried. The one suitor she did eventually love – Cardinal Louis La Vallette; in the curiosity of the times, a Cardinal without priestly ordination – died on military campaign in Italy before he could be released from his ecclesial duties.

But Marie’s one enduring passion, and the key to her life, was her Catholic faith. She twice tried to join a Carmelite community. Her uncle blocked it both times; her help was simply too valuable. After Richelieu’s death, Marie spent much of her time and immense fortune supporting Catholic missionary efforts in Asia, North America, Protestant Europe, and Muslim North Africa.

She ransomed hundreds of Christian slaves from Islamic captivity. She was a mentor to St. Vincent de Paul, a friend to other saints, and a patroness of numerous ministries of the Jesuits, Daughters of Charity, Augustinians, and other religious congregations.

The very best historical biographies fire the imagination and read like great novels. . .except these stories actually happened. What Bronwen McShea achieves so memorably with the life of Marie Madeleine de Vignerot in La Duchesse simply proves the point.

You may also enjoy:

Brad Miner’s Mary the Great

Carrie Gress’s Feminism’s Unexpected Cure