Sometimes the solution to a supposed problem in a work of literature or an historical account is right in front of our eyes, and we don’t see it. And it’s not always because our wills are not right. When we read, we bring into play, unconsciously, a world of expectations as to what an author is supposed to do, when the author either has no inkling that we expect him to do other than what he is doing, or he is counting on our wrong expectations in order to correct them.

I’ve long noted the phenomenon when it comes to literary criticism of a work from the early modern era or before. Critics used to say that the Anglo-Saxon poem The Dream of the Rood had two authors, the dramatic, muscular one who often launches into hypermetric verse when he is describing the crucifixion of Christ as a warrior’s great triumph, and the calm homiletic one who never uses the hypermetric at all.

They don’t say so anymore, because we’ve been persuaded that Ezra Pound – who insisted there were two authors, one he admired and one he scorned – was laying the poem on his own Procrustean bed, lopping off the limbs that wouldn’t fit his prescriptions; and so were all the critics who followed along.

The great nineteenth-century actor Tommaso Salvini, a devotee of Shakespeare, wrote that the Bard made a dramatic error in having the ghost of the old King Hamlet appear first on stage to Horatio and the soldiers, rather than have that appearance merely described in a quick account to young Hamlet.

But Shakespeare’s point was, in part, to contrast their reaction to the ghost with Hamlet’s reaction later on. “It started like a guilty thing / Upon a fearful summons,” says Horatio; an ominous observation, casting a shadow over our willingness to believe all that the ghost will say to Hamlet, and our decision to trust his intentions even if he is revealing facts.

If, as Antonio says in The Merchant of Venice, “the devil can cite Scripture to his purpose,” then the damned can tell the truth, too, to destroy us, as Hamlet himself will note later on.

So I come to the Gospels, and I ask, “If Jesus appeared to the disciples many times after the resurrection, even to five hundred at once, as Saint Paul says, why don’t we get more accounts of them?” Call it the idle curiosity of someone brought up on newspapers.

But suppose you are at Bethany when Lazarus comes forth from the tomb. Are you going to approach him with your microphone, for an interview? Ask him whether he is going to vote Pharisee or Sadducee, or break for the third-party Zealots? The point is that he was dead, and now he is alive.

The point with Jesus’ resurrection is that he was brutally murdered, his lungs and heart pierced by the lance after his death, and that on the third day he rose from the dead, in the flesh, but not a resuscitated flesh; with the marks of his wounds, but not their injuries; occupying place and time, but not as we with our mortal bodies do. That is the great fact, and the rest is but distraction.

Notice that none of the Gospel writers describes what Jesus looked like. It would have been the easiest thing in the world for them to do, since there were thousands of people readily available who had seen Jesus, who had lived with him, walked with him, eaten with him, spoken with him. But they do not do it.

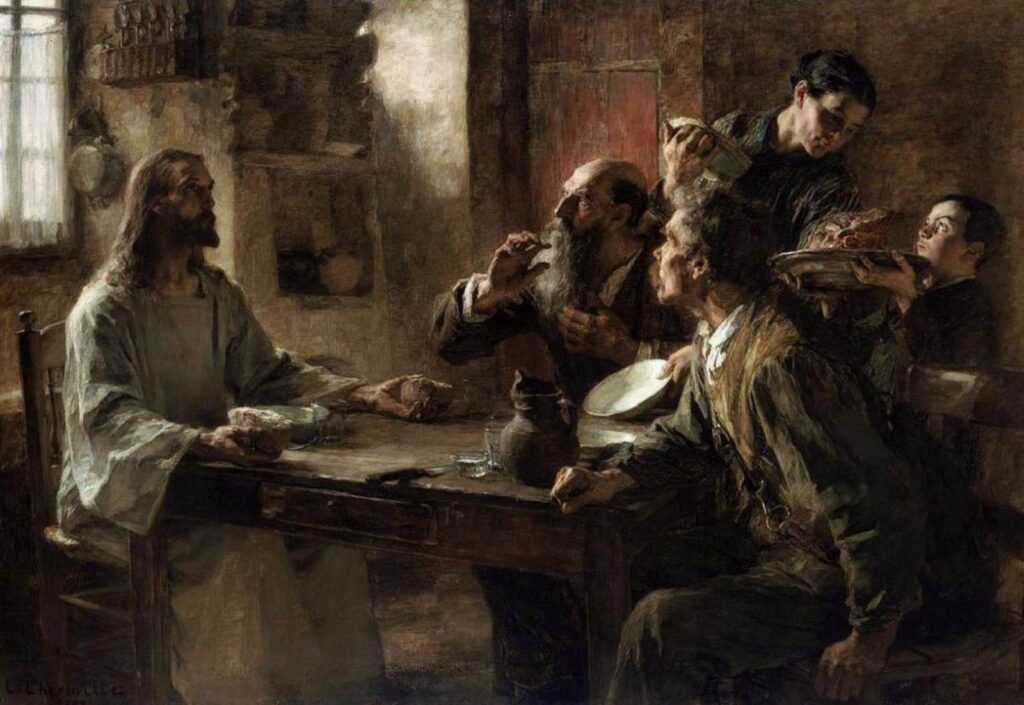

We do get some eyewitness details of the surroundings – especially from John; but they are not there to set a scene, as a modern novelist would use them. They are the kinds of things that jog your memory, like the size of the jars at Cana, or the charcoal fire outside of the praetorium, or the site where something happened, like the well in Samaria.

To speak then about the color of Jesus’ hair would be an irrelevance.

But what of the fact that Saint Paul in his letters does not echo the parables of Jesus? Doesn’t that prove that the gospels were not written yet? But consider: Saint Luke himself, in Acts, does not echo the parables in his own Gospel which he had already written, and none of the other writers in the New Testament, no matter how late it is said that they wrote, analyzes the Gospels either.

If the Gospels must be late because Paul does not play the exegete of Jesus’ teachings, then they must come later than everything else in the New Testament too, for the same reason. But nobody believes that. If the author of Revelation is not Saint John (as I believe he is), and if he is writing after John and the other evangelists, why does he not ring up Jesus’ predictions of the last days, for example, in Matthew 25?

We must then shed our preconceptions. To us, the heart of the Gospels may be the Sermon on the Mount. And sure enough, the entire New Testament is steeped in the spirit and the significance of Jesus’ teachings. But the authors did not want to do with the words of Jesus what the rabbis did with the words of the prophets. They did not reduce Jesus to a speech-maker – to a Jewish Socrates.

The focus is always on what he did and who he is; and that intense focus is also cosmic, in a way that using the words of Jesus as good advice on how to live cannot be so.

The evangelists were illumined by the glory of a cosmic fact, one that shakes the old world to its foundations. Once we keep that in mind, we will not do to them what Salvini did, with all good will, to Shakespeare. Of them too we may say, “Let me be less, and let them be more.”

__________