Lenin – who gave the world the socialist murder machine formerly known as the Soviet Union – loved music when he was in exile. Once he returned to Russia, to spark the Bolshevik Revolution, he said he couldn’t much listen to music anymore: “It affects your nerves, makes you want to say stupid nice things and stroke the heads of people who could create such beauty while living in this vile hell.”

There was, is, and always will be a kind of radical Lover of Mankind who will sacrifice saying “stupid nice things” and even actual living people to some harebrained scheme that makes our fallen world still more vile. But there’s a lesson here, even for us in well-off, tolerant-to-a-fault societies, who may be tempted to think that our whole lives should be consumed by cultural, political, or spiritual wars.

People in a position like mine may be especially susceptible to this temptation, which is why active measures, in a different key, are necessary. I myself try to play the piano at least a half-hour every morning because it reminds me – if not necessarily people in the house who have to listen – that God’s Creation is a harmony, a discordant harmony to be sure, but a definite concord of creatures, not perpetual warfare.

Many people send me books, good books, about our current turmoil. I appreciate these, but as someone always engaged in heavy reading for several book-writing projects of my own, often can’t get to them or even acknowledge the favor. But a generous TCT supporter gave me a book at dinner this week that has captured my attention: Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers by Patrick Kavanaugh, a conductor who is also director of the Christian Performing Arts Fellowship.

It’s a succinct and clear account of the religious beliefs of twenty well-known classical composers, from Bach to Messiaen – and many greats in between, a wonderful record of how close music and spirit have been, until very recently, in Western culture.

The great Johann Sebastian Bach, for example, had no difficulty in seeing God and music intertwined. As he once said, “Music’s only purpose should be for the glory of God and the recreation of the human spirit.” A humble, if prodigious, musical worker (he famously walked 200 miles to hear then-celebrated organist Dieterich Buxtehude), he regularly put J.J. (Jesu Juva– “Jesus help”) on the page before composing.

There were similar examples in the same period. A servant stumbled in on Georg Friedrich Handel just as he finished writing the Hallelujah Chorus for the Messiah, and found him in tears: “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God Himself.” (Incredibly, if you discount divine inspiration, Handel had produced the 260-page score of this evangelization in sound in just twenty-four days.)

These musicians were quite at peace and confident in their Christian faith. Kavanaugh doesn’t much write about the times in which they lived. But it’s significant that they could attribute their works to God’s gifts, despite the fact that their lives overlapped with several of the major anti-Christian figures of the Enlightenment such as Diderot, Hume, and Voltaire. You won’t read that in most mainstream accounts of our roots in the eighteenth-century Enlightenment.

Bach and Handel were, of course, Protestants, but it’s striking and little known how many of the greatest classical composers have been Catholic (in varying degrees) over the centuries: Haydn (the most steady and orthodox of them all), but also Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Liszt, Chopin, Bruckner, Gounod, Dvorak, Elgar, Messiaen. (Stravinsky, perhaps the greatest 20th-century composer – was Russian Orthodox – but wrote a Mass and other sacred music.) Despite their differences, they were virtually all united in believing that inspiration came from and returned praise to the Creator Himself.

The great modern Catholic poet Paul Claudel was fond of the phrase Noli impedire musicam (“Don’t impede the music”), a rather loose translation of Sirach 32:5 about not gabbing during a feast when there’s music playing. He suggested it had a larger meaning: that we often mar the natural music in the world with our self-important preoccupations.

There’s much talk these days about that mysterious phrase from Dostoyevsky, “Beauty will save the world.” St. John Paul II and Alexander Solzhenitsyn have given us some valuable reflections on that theme. And there’s this from Benedict XVI:

The encounter with the beautiful can become the wound of the arrow that strikes the heart and in this way opens our eyes, so that later, from this experience, we take the criteria for judgement and can correctly evaluate the arguments. For me an unforgettable experience was the Bach concert that Leonard Bernstein conducted in Munich after the sudden death of Karl Richter. I was sitting next to the Lutheran Bishop Hanselmann. When the last note of one of the great Thomas-Kantor-Cantatas triumphantly faded away, we looked at each other spontaneously and right then we said: “Anyone who has heard this, knows that the faith is true.”

I’m not entirely convinced. Bernstein and many modern musicians seem to make the music itself into an idol, and doubt the God behind the music in whom so many of the great composers believed.

But Benedict is certainly right about how important is the “wound” that beauty inflicts on the heart – and the importance of such wounds in opening us up to realities that our arguments and logic often deal with poorly or even overlook.

Whenever I write about subjects like this, usually in the summer or other times we can breathe a little more deeply and look to larger realms, someone inevitably writes to say that I should give up aery-faery things, because what we really need is a militant political party. True, of course, to a point. We also need a Church Militant.

But I also remember Lenin – and the value of saying “nice stupid things” – and the dangers of letting the Bolsheviks impede the music and dictate the whole agenda for our lives.

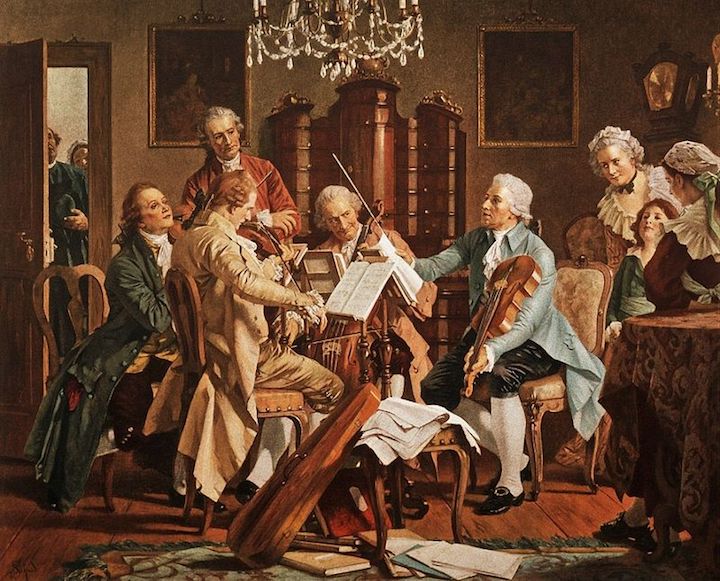

*Image: Joseph Haydn playing in and conducting his string quartet by an anonymous 19thcentury artist [Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna]