Reading the Declaration on Human Dignity (“Infinite Dignity”), issued by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) yesterday, reminds me of an old teacher-student story. A student submits an assigned essay, and the teacher returns it with the comment, “What you’ve written here is both good and new. Unfortunately, what’s good in it is not new, and what’s new is not. . .” But let’s break off the story there. And following the Christian rule of charity in all things, say of the Declaration, what’s new in it is . . . yet to be determined.

Because in roughly the first half of its sixty-six paragraphs, the document seeks to situate itself in line with recent popes and classical Catholic teaching. It cites Paul VI, JPII, Benedict, Francis (about half the citations, of course). And in a footnote even reaches back to Leo XIII, Piuses XI & XII, and the Vatican II documents Dignitatis humanae and Gaudium et spes. At the press conference introducing the Declaration, Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, head of the DDF, made a point of opening with the observation that the very title of the text came from a 1980 speech St. John Paul gave to a handicapped group in Osnabrück, Germany. Indeed, said the Cardinal, it’s not by chance that the document is even officially dated April 2, the 19th anniversary of JPII’s death.

All of this cannot help but make the alert reader think that the drafters – and those who approved the final text – wanted to frontload ample exculpatory evidence against any objections that might follow.

And inevitably, objections will. Because in several respects this apotheosis of human dignity raises more questions than it settles. (“Infinite” human dignity in JPII’s hands was one thing; now, it may mean something very different.)

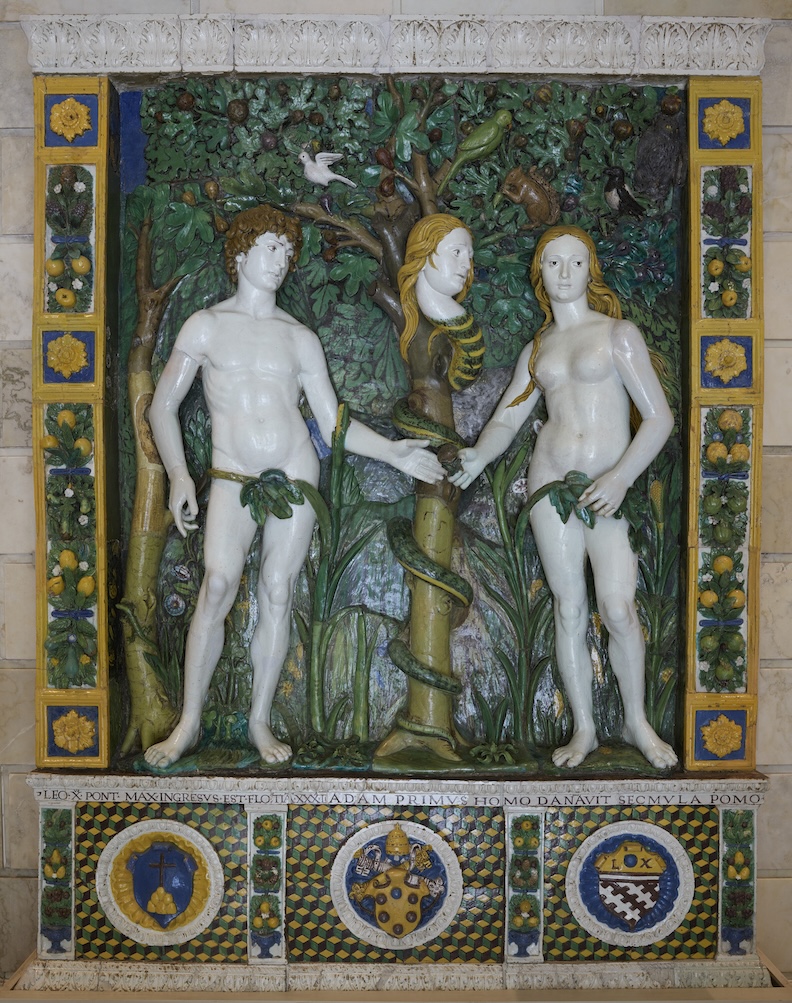

It’s good to have a document, however, that affirms two fundamental Biblical notions “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him.” Hence, “infinite” dignity. And propers to Cardinal Fernández that he emphasized during the presentation “male and female he created them.”

But much of the world already believes in human dignity and freedom well beyond those limits and responsibilities. And the takeaway from all this talk – what’s communicated as opposed to what’s actually said – may be quite different than the actual words.

On the one hand, it’s repeatedly affirmed that there’s an ontological dignity to every human being from conception to natural death. (Ontological, here, means it’s built into our very being and nature by God and therefore “cannot be lost.”)

So far so good.

But there are other kinds of dignity – moral, social, existential as the Declaration properly recognizes. These may exist to a greater or lesser, proper or improper degree. Morally bad acts, for example, are not only an affront to the human dignity of others. They diminish our own moral dignity – and freedom – though never, we are told repeatedly, to the point that we lose our ontological dignity.

This leads to a certain lack of Catholic realism – even basic consistency – in some of the arguments in the second half of the document. To be fair, specific matters were left in brief, general terms – something the Cardinal says was done deliberately to keep the document relatively short.

Still, this leads to oddities. For some reason, for example, intrinsic dignity is the reason the death penalty is no longer “admissible.” But not only has it been seen since the early days of the Church as “admissible” (on this see the definitive work by Joseph Bessette and Edward Feser). Capital punishment has even been valued at times as a matter of justice – and human dignity – for both perpetrator and victim. It takes human wrongs seriously in the way they are punished.

The Declaration also affirms the right of self-defense, but goes on: “We can no longer think of war as a solution because its risks will probably always be greater than its supposed benefits. In view of this, it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibility of a ‘just war.’”

Yet Ukraine is fighting a just war. And it won’t be the last one – until human wickedness leaves the earth.

The problem is not only about the arguments. There’s also a question about what the Church has recently done. For example, the Declaration speaks eloquently about violence against women. Yet when two women decided finally to come forward publicly about Fr. Marko Rupnik, a friend of the pope’s and a former Jesuit, who close to two dozen women have claimed abused them sexually (including some rituals that can only be called satanic), appropriate action didn’t follow. Fr. Rupnik still functions as a priest in Rome.

The Declaration also asserts with some force in opposition to gender theory:

it intends to deny the greatest possible difference that exists between living beings: sexual difference. This foundational difference is not only the greatest imaginable difference but is also the most beautiful and most powerful of them. In the male-female couple, this difference achieves the most marvelous of reciprocities. It thus becomes the source of that miracle that never ceases to surprise us: the arrival of new human beings in the world.

Yet this affirmation in theory comes into no little conflict with how the Church has recently acted in practice. In his oral presentation, for example, the Cardinal pointed not merely to the teachings of Francis, but his attitudes and behavior towards all people, a matter of welcoming and respect. This has been a constant – and often confusing – feature of his papacy.

On the one hand, we have the right understanding of gender theory. On the other, the pope meets with Fr. James Martin and the leaders of New Ways Ministries, who clearly are advocates for points on the spectrum of gender theory, and has (incredibly) described them as practicing “the style of God.”

Francis has no difficulty castigating priests in general, even psychoanalyzing, at a distance, the ones he regards as “rigid.” But where’s the will, when it’s hard, to evangelize, to confront, to urge repentance? Precisely on the difficult issues. It’s easy to denounce war, human trafficking, environmental damage, violence against women, surrogacy, etc. Much harder to enter the fray where the Church is most needed.

Affirming human dignity will not stop the raids of the rainbow warriors, Trans Visibility Day on Easter, two gay pride months, or Drag Queen Story Hours for children. The only thing with a chance of rolling back these destructive threats to human dignity is a Church in a much more militant stance.

And despite some encouraging words, there’s little real fight in the Declaration, especially given the current moment, when militant activists of various stripes need to be not just observed and classified, but effectively resisted. Even driven back, for the very sake of human dignity.

Yes, explain why all these things harm human dignity, as the document does well enough. While the explaining continues, however – contradicted by the indiscriminate “welcoming” – children are being mutilated, families torn asunder, marriage sidelined, populations are shrinking. And one can easily imagine the takeaway for those with a will to misunderstand. And not entirely in error. As with the “Who am I to judge?” fiasco, the message being transmitted to many in our culture, despite the actual words, will likely be to say, “Pope Francis says that I’ve got intrinsic – infinite – dignity. Back off, man.”