The Feast of the Ascension seems on a par with Easter. It gets equal attention in the creeds: “On the third day, he arose from the dead. He ascended into heaven.” It is the first doctrine Jesus preaches upon his Resurrection. He tells Mary Magdalene, “go to my brethren and say to them” – not, “I am risen” – but rather “I ascend to my Father and to your Father, to my God and your God.” (John 20:17) She saw that he had risen. The Lord did not need to tell her that. But He does tell her, as a matter of first importance, that He will ascend.

Logically, if the Lord did not ascend to Heaven, if Heaven was not His goal and home, then his resurrection would have been “for this world” solely, just like the resurrection of Lazarus, and he would have died once more. That is, the resurrection which we celebrate at Easter by definition is a resurrection for someplace other than this current world as it is.

Not unexpectedly, the Eastern Churches use apt language to signify the mystery’s nature. They call it the episôzomenê (emphasis on the penult), “the day on which our salvation attains its perfection.” If to deny a thing’s perfection is to deny the good of that thing, then to deny the Ascension is to deny the goodness of Easter.

The Church accordingly has given the Feast the highest importance. “It is one of the Ecumenical feasts ranking with the feasts of the Passion, of Easter and of Pentecost among the most solemn in the calendar,” says the Catholic Encyclopedia. By the time of St. Augustine that saint could say “this day is being celebrated all over the world,” a sign of its great antiquity.

The Ascension was deemed so important that Pentecost could be assimilated to it: the Council of Elvira (c. 300 AD) condemned the apparently common practice then of celebrating Pentecost along with the Ascension on the 40th day after Easter, instead of doing so separately on the 50th day.

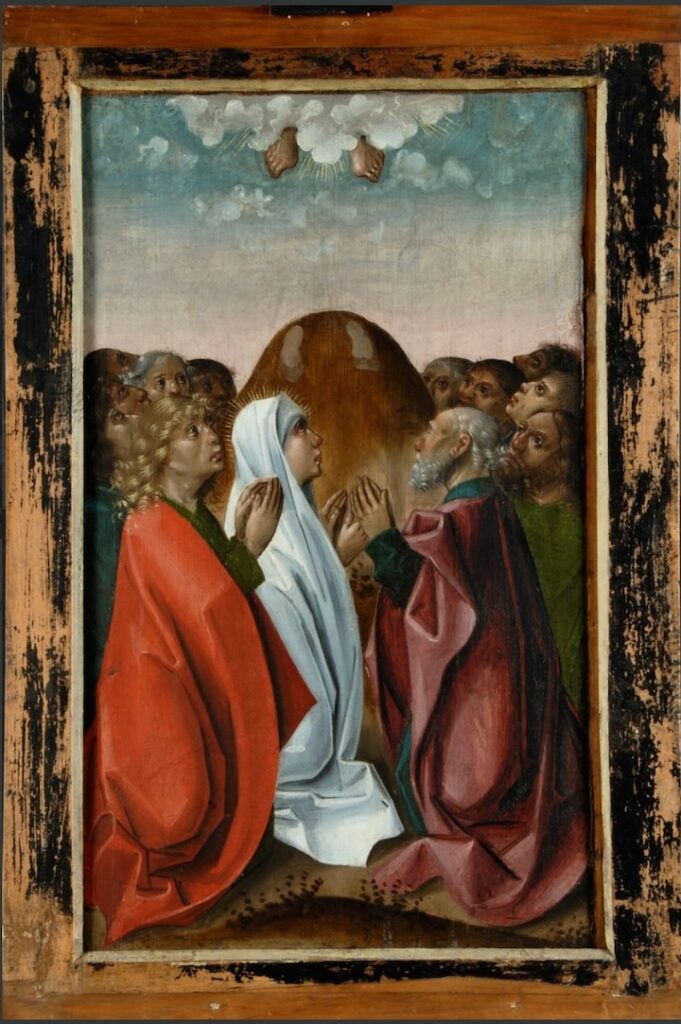

Canny exegetes have pointed out that the nine days during which Mary prayed with the Apostles in the upper room between the Ascension and Pentecost constituted the very first novena. The feast of the Ascension, therefore, memorializes the beginning of a special time of prayer in the church.

Pope Leo XIII, doing more than notice the fact, “decreed and commanded” that “throughout the whole Catholic Church, this year and in every subsequent year, a Novena shall take place before Whit-Sunday, in all parish churches, and also, if the local Ordinaries think fit, in other churches and oratories.”

The period was a rich time of grace in his view. Therefore, he granted “in perpetuity, from the Treasury of the Church,” a plenary indulgence to anyone who during this time, either publicly or privately, offered prayers to the Holy Spirit (while satisfying the usual conditions: encyclical letter, Divinum illud munus).

St. Augustine preached several famous sermons on the Ascension. What meaning does he see in it?

It is the feast he says that most corresponds to the Incarnation. (Sermon 262) Just as Christ emptied Himself to become man (Philippians 2:6), so God now exalts Him. To live a Christianity without the Ascension then is to live a life of emptying solely – at the extreme, a life of activism or nihilism. And dare one say that we cannot grasp Christmas without grasping its bookend?

It is the feast, too, where Christ’s protection over us is displayed and as if vindicated (Sermon 263): “The reason He rose again was to show us an example of resurrection, and the reason He ascended was to protect us from above.” Without the Ascension then: anxiety.

And one cannot grasp the victory of Christ without seeing it in the Ascension. Christ is not simply a lamb, but also a lion (Revelation 5:5), Augustine says. As a gentle lamb, he was slain: as a lion, he conquered the devil, also a lion, who prowls about the earth to devour souls. (1 Peter 5:8) “Against the lion, a lion,” says the saint. To live Christianity without the Ascension is to be a lamb solely and not a lion.

Yet it is not merely the power of the Lord as shown in the Ascension which matters, St. Augustine says, but also his deliberately being lifted up high. It’s just like: when it looks like you have lost a contest, and others begin to exult over you, and yet in the end you win, then two things become necessary: not merely that you win, but also that you exultin the win, for instance by raising a trophy. Here the saint uses his famous language of a mousetrap:

The devil was exultant when Christ died, and by that very death of Christ was the devil conquered; it’s as if he took the bait in a mousetrap. He was delighted at the death, as being the commander of death; what he delighted in, that’s where the trap was set for him. The mousetrap for the devil was the cross of the Lord; the bait he would be caught by, the death of the Lord. And our Lord Jesus Christ rose again.

But there’s more. Corresponding to the devil’s delight, and the mockery of the crowds – “If He is the Son of God, let Him come down from the cross” (Matthew 27:4), there must be the raising of a trophy in victory – which is the Ascension.

We live effectively in a Church without an Ascension. It has been moved to Sunday – assuredly, not to make it more important. (You may not even notice it two days hence. Did you care when yesterday went by?) Our bishops presumably sense that if it were kept on the Thursday, no one would see a point in going. We live in grave discontinuity with our brothers and sisters in the past. I see no way out but: the study by Catholics today, ardently, of our tradition.

__________

You may also enjoy:

+James V. Schall, S.J. The Prince of This World

Anthony Esolen The Glory of a Cosmic Fact