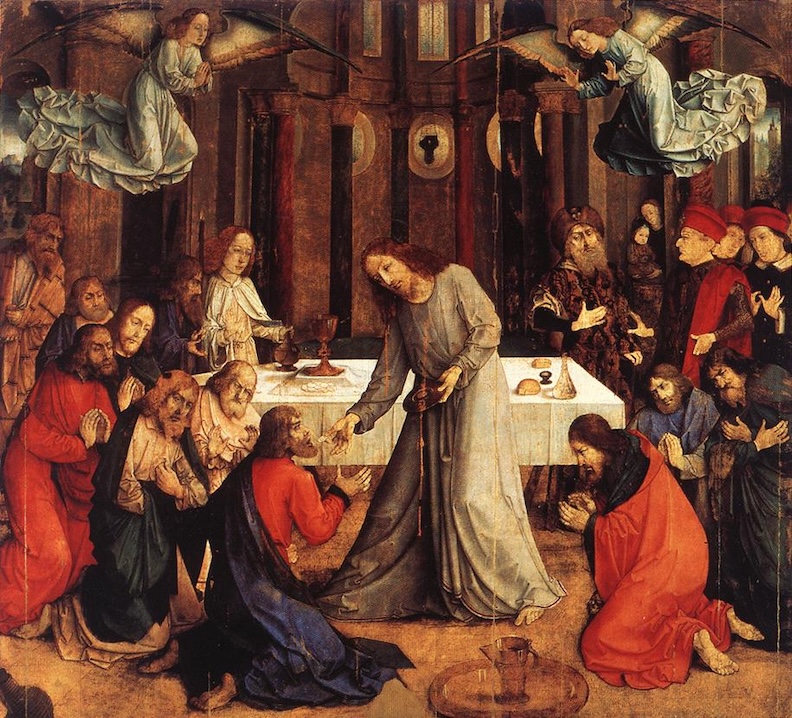

As Laetare Sunday recedes, Catholics become more focused on approaching Passion Week. I like to encourage Catholics to embrace their faith as true by thinking about it – because only what is definite is true. So in preparation for Holy Thursday, I’d like to contemplate in advance with you four fascinating questions which Saint Thomas considers about the Last Supper. (ST III, 81)

First, he raises the question most of us have thought about, whether Judas received the sacred mysteries, or did Judas depart before these were distributed? St. Thomas puts the question in the active voice: Did Jesus give the sacred mysteries to Judas or not? Which is correct, because clearly whether Judas received was up to the will of Christ.

From St. Thomas’s discussion and commentaries elsewhere it becomes clear that the consensus among the Fathers was that Judas did receive Communion. St. Hilary, who denied it, was an outlier.

The main argument against Judas’s receiving, tellingly, is that it would have been wrong for Our Lord to give the mysteries to Judas, because Judas was an unrepentant sinner, set on betraying Jesus: pearls before swine. For St. Thomas, this argument would be correct if Judas were a public sinner. But his sin was not known. “Consequently, Christ did not repel Judas from Communion; so as to furnish an example that such secret sinners are not to be repelled by other priests.”

A lesson then for modern clerics: you don’t imitate our Lord unless you allow the distinction of public versus private sinner to be decisive. (CIC, canon 915) And for laypersons: the many Judases you see today, are only following in the footsteps of Judas himself.

Second, St. Thomas asks whether Jesus too received Communion at the Last Supper. Did He eat His own Body and drink His own Blood? Or did He simply “take” the bread and the cup without consuming? After all, Scripture does not say explicitly that He did. Furthermore, He would have no need of the grace from the sacrament. And besides, no whole can contain itself – only a part of a whole can be placed within a whole – and yet the Eucharistic bread is the whole Christ. The whole body of Christ contained in the body of Christ is an absurdity.

St. Thomas finds it improbable, despite the silence of Scripture on this particular point, that Jesus did not consume the consecrated bread and wine, because “Christ Himself was the first to fulfill what He required others to observe,” as when He sought baptism from John. The argument about parts and wholes is foolishness: the spatial dimensions of the whole Christ in the Eucharist are determined by the size and shape of the bread, not by Christ’s body. Besides, the argument would show that no one could consume the Lord’s body.

As for the argument that Christ had no need of the sacrament, St. Thomas says something that reveals some of his own Eucharistic piety. He says that there are actually two effects of Communion: an increase in habitual grace, and “a certain actual delectation of spiritual sweetness.” The Lord enjoyed the second and indeed it explains why He said, “With desire I have desired to eat this Pasch with you.” (Luke 22:15)

St. Thomas’s third and fourth questions concern whether it was the mortal Body and Blood of Jesus which were present under the species of bread and wine at the Last Supper, or rather the glorious, resurrected body, which was incapable of suffering (“impassible”)?

St. Thomas has no doubts on this point: “For it is manifest that the same body of Christ which was then seen by the disciples in its own species, was received by them under the sacramental species. But as seen in its own species it was not impassible; nay more, it was ready for the Passion. Therefore, neither was Christ’s body impassible when given under the sacramental species.”

Christ gave His apostles the very same body and blood that they saw before their eyes on that evening. And that body was about to be tortured, and that blood was about to be poured out.

But suppose then (this is the fourth question), that an apostle had reserved the Eucharistic bread in a pyx. Would it have been correct to say, as regards that sacred bread at 3pm Friday the next day, that “Christ himself has just died there?” It was a passible body; it is just the body that Christ’s body is; and Christ has just died. Therefore, Christ has just died in the sacrament.

Yes, says St. Thomas, without question: “Christ’s body is substantially the same in this sacrament, as in its proper species, but not after the same fashion.” What happens to the Lord, therefore, happens to that Body. But not directly so: you could not have tortured the Lord’s body by ripping or piercing the bread.

The Body in the Eucharist is “impassible” to outside objects, as under the species of bread. But the Body in the Eucharist does indeed change, if the Lord’s body undergoes in itself change through suffering. “All that belongs to Christ, as He is in Himself, can be attributed to Him both in His proper species, and as He exists in the sacrament; such as to live, to die, to grieve, to be animate or inanimate, and the like.”

Here is an interesting corollary. We are used to saying, rightly, that it is not necessary to receive the cup as well as the bread, because Body and Blood are both present in each. And yet this is true, only when body and blood are joined in the living Christ. When Christ is dead, his body and blood are separated. Therefore, had the Eucharist been reserved in a pyx, between Friday 3pm and Our Lord’s resurrection, it would have been the Body only.