Countless voices are being raised among bishops, priests, and laity calling for credible investigations of the McCarrick scandal, sexual abuse cover-ups, and the crisis in sexual morality, particularly regarding homosexual activity among the clergy. Those issues warrant detailed examination, especially in light of the New Paradigm for morality advocated by leading prelates, which accommodates contraception, homosexual and other extra-marital sexual activity, and remarriage.

The astonishing allegations of Archbishop Viganò, however, direct us to a much deeper crisis than sexual sins and false theology: the abuse of pastoral authority, both by clerical abusers and the bishops who fail to protect the flock.

To say that clerical abuse is about authority rather than lust doesn’t exclude the role sexuality can play, but links that gratification to the exercise of power. For clergy, authority is rooted in their sacramental office as shepherds of Jesus’ flock. Predatory clerics and the bishops who failed to vindicate victims are guilty, therefore, not only of the misuse of office, but the abuse of a spiritual relationship. They are fathers and brothers, images of Christ, who violated the trust of God’s people coming to them for support and protection.

Whether the abusers and the bishops acted sinfully, that is, with full knowledge and freedom, is an important matter. The central issue, however, is that their actions caused grave injury to the members of the Body of Christ. Justice and charity demand that the damage be investigated and remedied to the extent possible, not just forgiven. This can include the offender’s removal from office.

Many cases of clerical abuse and of episcopal failure were not isolated events, accounted for by saying, “we all sin and make mistakes.” These were established patterns of destructive behavior that had become second nature to the abuser or the bishop. Such habits are called vices. They are deep-seated dispositions for continual bad behavior that indicate a state of corruption or dysfunction.

Repeat abusers are unwilling or unable to alter their behavior in a way that would surrender the power they use to gratify themselves. Thus, until their vicious dispositions change, they will not take steps to restore justice and charity. They may mouth various acts of regret or amendment of life, but these are done only to repair their status.

This is why the role of the bishops is paramount. It falls to them to find an effective means of providing a just and charitable outcome for the victim and, in that context, for the perpetrator as well. Here is where too many bishops revealed their own corruption or dysfunction, compounding the injury by their misuse of episcopal authority. This explains why victims, their families, laypeople, and clerics have at times also felt abused by bishops – or even by Vatican officials.

Some of the bishops who repeatedly failed claimed that, decades ago, they treated abuse as sin. That’s not true. Had they treated it as sin, they would have required the perpetrator to admit the wrong, make restitution to his victim (financially and in other ways), do penance, and amend his life. They would then have recognized a repetition not as a “lapse,” but as a sign of a vicious habit which was compulsive or willful. In either case, concern for the well-being of the faithful and the priest should have led to no further assignments.

Other bishops who failed claimed that more recently they treated abuse like a disease. That’s unlikely. Treatment plans usually called for supervision and on-going care. In cases of repeated abuse, bishops often didn’t ensure those steps were diligently followed.

A far larger number of bishops failed by not cultivating an environment in which clergy or laity could approach them with concerns. Admittedly this changed after 2002 so that at least allegations of abuse of minors were received. But with rare exceptions, such as the Diocese of Tyler, there haven’t been policies that require reporting other clerical violations of Christian faith and morals, such as false teaching, sexual relations with men or women, financial abuse of the parish or individual parishioners, addiction to alcohol or pornography, etc.

It must be recognized, then, that diocesan or Vatican bishops who repeatedly fail to vindicate victims exposed to various forms of clerical abuse demonstrate a level of corruption or dysfunction that itself constitutes an abuse of power. These failures are much more than mistakes. Such behavior has become second nature to these bishops in the administrative exercise of their office.

During the decades of the abuse crisis, neither the bishops nor the Holy See has provided effective accountability for corrupt or dysfunctional bishops. Some claim the bishops lack authority in this area, yet nothing prohibits their presenting a policy to Rome. This passivity, too, is an abuse of power that denies justice and charity to the people of God. It creates a situation that makes it difficult for even a Vatican investigation to be considered credible.

In the McCarrick scandal, the bishops of Newark and Metuchen knew the allegations concealed by the settlements. Yet Cardinal Wuerl insists no one warned him – which, if true, means the Vatican also kept quiet. If so, their cover-up prevented finding and helping seminarians and priests exploited by the ex-cardinal. It also enabled the retired McCarrick to fraternize routinely with seminarians. In an indirect way, Wuerl’s account, then, alleges an abuse of power by bishops in the United States and Rome as disturbing as Viganò’s charges.

We must credibly investigate abusers like McCarrick, the crisis of sexual morality linked to the New Paradigm, and the bishops who have enabled these and other outrages against God’s people. Wuerl’s and Viganò’s claims require us to examine the nuncios and the curia. But we must go further. To confront the abuse of pastoral authority, we must establish effective means of reporting, investigating, and correcting violations of Catholic faith and morals by Church personnel, from part-time volunteers to the bishops themselves. Justice and charity demand it. So too does Jesus, the ultimate victim – and judge – of all this abuse.

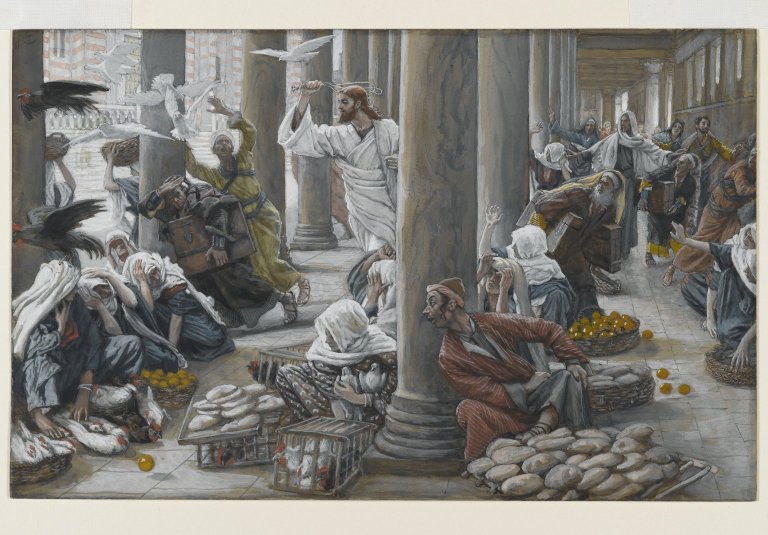

*Image: The Merchants Chased from the Temple (Les vendeurs chassés du Temple) by J.J. Tissot, c. 1890 [Brooklyn Museum]