One aspect of getting older, and wiser, is the shedding of once comforting, but in fact naïve illusions about individuals or groups. We normally trust that certain people and groups who profess to carry out a particular and demanding mission in society are in fact going to do just that. Past performance, as far as we know, was good and the future promises more of the same.

But reality is more complicated than that. Illusions give way to a more realistic understanding. High expectations about people and groups are often shown to be illusions based on incomplete knowledge of their past performance. The reputation for competence and integrity may exist largely because contradictory evidence of failure was carefully hidden from public view, or downplayed when made public.

The overcoming of the false impressions that once buttressed our appreciation of persons and groups is a good and necessary step in facing the world as it is, not as we would wish it to be. I remember being told that growth into maturity consists in the ever-increasing ability to deal effectively with complexity. Simplistic judgments are often attractive but are not usually sufficient.

Knowing the complexity of things, however, should not mean losing our sense of awe for God’s providence in guiding the course of the world and His Church. Discovering facts and casting aside illusions is unsettling, especially when it comes to the way the Church manages her affairs, which means how the leaders of the Church carry out their duties, which should be in absolute fidelity to the teaching of Christ.

These year-end reflections on illusion and reality are of course prompted by what has been happening in our Church during the past twelve months. The reality is that the once common high regard for bishops as a group, and for many individual bishops, has been shattered by the revelation of sexual abuse and episcopal patterns of covering up immorality and malfeasance.

Catholics in the United States and elsewhere were genuinely stunned to discover the sordid story of ex-Cardinal McCarrick’s depredations, the hidden payoffs made by other bishops to seminarian and priest victims of McCarrick, and the seemingly unhurried response of the Holy See in pursuing these canonical crimes.

McCarrick resigned from the College of Cardinals in July and was ordered to live a life of prayer and penance without travel and public appearances while awaiting completion of a canonical process. He was first accused of molesting a seminarian in September 2017. The Holy See judged this accusation to be credible in June 2018. McCarrick has not been tried by a canonical court as of December 2018. Why the delay if the evidence was compelling six months ago?

In August, the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report was released and precipitated the downfall of the most influential American cardinal, Washington’s Archbishop Donald Wuerl. Shortly thereafter, Bishop Michael Bransfield of Wheeling, West Virginia, a McCarrick protégé, was abruptly retired and placed under investigation for sexual harassment of adults.

There followed accusations by the former Nuncio to the United States, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, that many people in the Holy See, in particular Pope Francis, knew about McCarrick’s immorality and abuse of authority and acted in ways that kept him from being held accountable.

When Pope Francis refused to answer journalists’ questions about Viganò’s charges on a flight back from Ireland, he frustrated those who want to know how McCarrick amassed such power and prestige when his behavior had been reported multiple times to the Holy See in the past. Francis told the journalists to do their job and look into Viganò’s charges. But when journalists started to call the cardinals and bishops named in Viganò’s memorandum no one wanted to respond. A cone of silence seemed to descend on the Vatican.

The American bishops asked for an investigation of McCarrick’s rise. The Holy See has only responded that a review of documents in various curial offices is being conducted. While a good first step, that hardly constitutes a thorough investigation. What about taking testimony from those in the know? Or promising to make public the evidence and the findings? Or inviting McCarrick’s victims to meet with the Holy Father and tell him directly what happened, as was the case in Chile?

The U.S. bishops were set to take concrete steps at their annual November meeting to put an end to a hierarchical culture in which priests, and even bishops such as McCarrick, were protected from revelations of crimes and allowed to continue in place, thanks to payoffs and confidentiality agreements. The last-minute instruction from the Holy See to take no action until after a February meeting in the Vatican was met with stunned incredulity. Is this the right way to address a five-alarm crisis of confidence in the Church and her leaders regarding horrendous crimes and malfeasance?

The faith and love of Catholics for Christ and His Church has been severely tried this year. The common expectation among Catholics that the bishops as a whole shared the same horror of sexual, and in particular of homosexual, immorality among the clergy has been shown to be an illusion. So be it.

Love for the Church has prompted laity to call for a reform of the hierarchy. Accountability for past failures to root out sexual immorality is the first necessity, as is a clear demonstration that a repeat of the career path of a Theodore McCarrick will be impossible in the future.

Bishops will only regain the respect of ordinary Catholics if they truly live up to what we all believe is the Church’s true mission, the salvation of souls. If the dark clouds of 2018 have a silver lining, it’s that there is now at least some chance that immoral and conniving priests and bishops will no longer be tolerated, protected, or promoted, but rather called to repent and held to account.

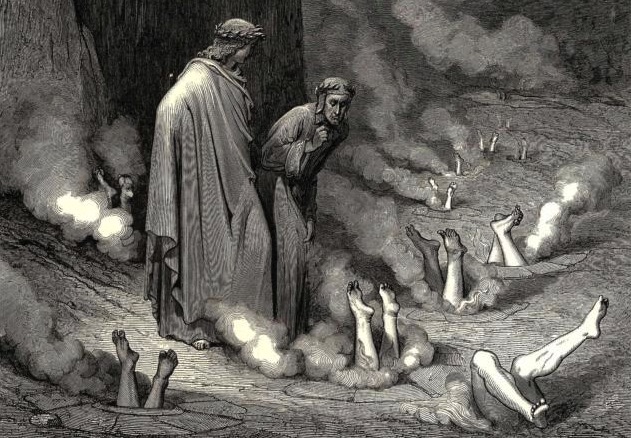

*Image: Dante and Virgil speak to Pope Nicholas III in the Eighth Circle of Hell by Gustave Doré, 1861 [The engraving was among a number Doré did illustrating The Divine Comedy. Nicholas III was pope from 1270-1280 and was accused of selling ecclesiastical offices, a.k.a. simony.]