Some men are born eunuchs, some become eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven, and some, to the great profit of unscrupulous surgeons and the pharmaceutical industry, are made eunuchs by fathers who have abandoned them and by mothers who, alas, have not.

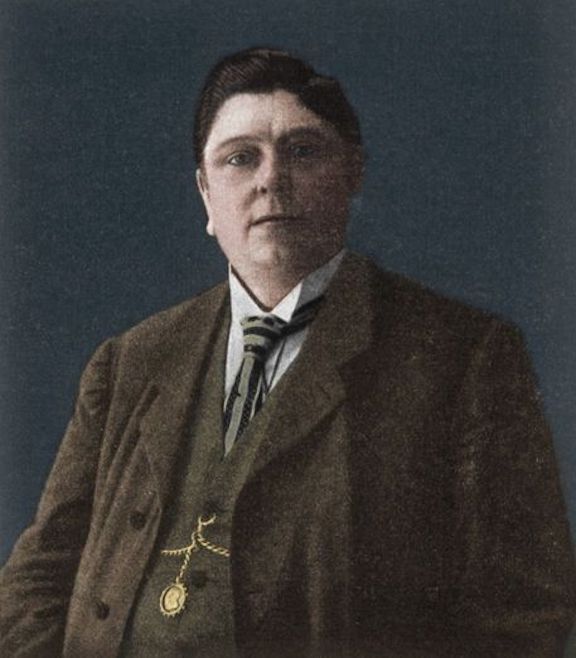

The last castrato to sing professionally, Alessandro Moreschi, died in 1922. It is not known whether he was castrated as a boy to preserve his voice or to remedy an inguinal hernia. A poor recording of his singing survives. His voice was a thready soprano, not the kind of thing for which even a partisan of the practice would have recommended mutilation. Perhaps it was once stronger and surer. We do not know.

The boy’s voice as he nears puberty has a peculiar quality to it, unique to the temporary configuration of his larynx and oral cavity. It produces a sound that choirmasters have treasured, and that inspired the talents of such composers as Palestrina, Allegri, and Bach.

To preserve that quality, sometimes a boy soprano would agree to be castrated. When castrati were the rage in the courts and music halls of the European Enlightenment, a talented boy in a family strapped for means would be tempted to endure the mutilation to provide for himself and his parents.

Naturally, he would be made welcome in the chambers of aristocratic ladies, who might play with him as they would with a puppy, without bringing shame to their husbands. That is the reason for the stratagem that the aptly named Horner plays in Wycherley’s salacious play, The Country Wife, though in his case the castration was supposed to have been required by what the English called the French disease, i.e., syphilis. A eunuch might also become a favorite receiver of favors from sodomites.

Unnatural and barbaric. Pope Leo XIII condemned the practice when he assumed the papacy in 1878. We will not see it again, thank God.

Instead we are seeing what is worse. Let us think the matter through.

Far be it from me to say anything exculpatory about the filthy priests whose vices warped the lives of many boys and young men and reduced many a parish and diocese to penury. But when those wicked men were done fondling the family jewels, they were at least still attached to the kid. He might still grow up to be a husband and father.

That is not the case when the boy “transitions,” that is, when he undergoes surgery to make it seem as if he is a girl when he is not and never can be.

The boy who decided to be mutilated did so to secure something that was in itself good. It is good, not evil, to have a beautiful voice. It is good to be the solo in Allegri’s Miserere. It is not good to mutilate the body for it. It is good, not evil, to provide for your family. It is not good to mutilate the body for it. It is good to praise God. It is not good to express your praise by what is contrary to nature, as mutilation is.

That boy was, in all likelihood, quite clear about what sex is, clearer than our children now are. He would have seen barnyard animals all his life. He would have slept in close quarters with other children. He would have developed a matter-of-fact attitude toward the embarrassing exigencies of our physical life. He will have been near men doing hard physical labor, every day of his life, labor that only men could do.

He was not rejecting his sex. He was not seized by the madness of believing that he was really a girl. He had not been taught in school that his sex was responsible for all the evil in the world. He would not have grown up in a divorce, with a mother infected with feminist fantasies, of a world bleached clean of the masculine. He would not have been subjected to story-time by men in drag. He would not have gazed at pornography, just a click away. He was not in the grip of delusion. The mutilation really would secure the good in question.

He would not be subjected to one surgery after another. His body would not be pumped full of dangerous drugs, including puberty-blockers and tissue-growing hormones, the latter likely to prove carcinogenic. He would not be sentenced to a lifetime of pharmaceutical dependence. His long bones would still grow. His body would be rather soft, but otherwise he would look like an ordinary man and not a freak. He would not be troweled out for a mock vagina.

He would not be a part of campaign to preserve and extend a thoroughly anti-Christian ethos, that of our sexual revolution. As I have said, he might be tempted to sodomy, but he would not be having the operation precisely so that he could engage in unnatural sexual relations. He was not embroiled in the destruction of language. He would have been called “he,” and would have thrown a fist at anybody who called him otherwise.

He was not setting a precedent for other violators of the meaning of the human: I mean those who believe we ought to be manufacturing ourselves, via genetic manipulation, artificial wombs, and other bridges thrown from man to the robot or the beast. He was not setting a precedent for sick people who believe they cannot be made whole unless they are made partial: I mean those who cannot endure the integrity of their bodies, and so they find an evil doctor somewhere who will remove a healthy arm or leg.

He was not the leading edge in subjecting the thoughts and speech and deeds of ordinary and normal people to the oversight of a vast totalizing state, and its symbioses in mass entertainment and mass schooling.

However sick it was to do that then, it is far sicker to do what we do now.