How is it that not all artists are conservatives?

This has always been a mystery for me. Plato seems to have thought most poets were sixth-rate human beings who sold phony wares to the masses, while Aristotle acknowledged that their talent for imitation was uncanny but most likely the result of some mental defect. Precedent counsels us, then, that there is no accounting for the looniness of writers and artists, the oft told tales of self-aggrandizement undone by self-destruction, irreverence, and contempt.

About many contemporary figures there is, of course, no mystery; many have frankly renounced the making of anything beautiful or even well-crafted in favor of the crude and shocking pronouncements of their (usually sexual-libertarian) political feelings. Such individuals do not concern me. What does rather is the good artist, the one who achieves something self-evidently great, and yet still seems to espouse principles of a flaccid and lawless sentimentalism not much different from the unreflecting relativism of a modern undergraduate.

It has always seemed to me that to apprentice oneself to a craft, to the virtue and practice of any art, perhaps especially the fine arts, is to recognize at least four truths. First, submission to a discipline is the price of mastery; second, the achievement of past masters is the tradition on which the making of the new fundamentally and continuously depends; third, the past as a whole is a beloved treasury that provides the material or subject for all art; and, most importantly, fourth, what is often called creativity is really just the making visible of laws and truths that were always present but previously concealed.

Each of these ideas strikes me as obviously conservative, though, we could just say they are classical. What they categorically forbid is the familiar pabulum one actually hears from not just the vaguely sentimental reader but from the practicing artist, and which passes under the name “romanticism”: that art is pure creativity, a lawless freedom that renounces the past and brings something merely new and self-expressive into being.

When Solzhenitsyn received the 1970 Nobel Prize, he addressed this question. Asking what is the nature of art, he referred first to the romantic idea:

One artist sees himself as the creator of an independent spiritual world; he hoists onto his shoulders the task of creating this world, of peopling it and of bearing the all-embracing responsibility for it; but he crumples beneath it, for a mortal genius is not capable of bearing such a burden.

The practice of art disproves the theory. Either the artist draws some strength from elsewhere or creates something bad. So Solzhenitsyn turns to the more obvious alternative, which I call conservative or classical:

Another artist, recognizing a higher power above, gladly works as a humble apprentice beneath God’s heaven; then, however, his responsibility for everything that is written or drawn, for the souls which perceive his work, is more exacting than ever. But, in return, it is not he who has created this world, not he who directs it, there is no doubt as to its foundations; the artist has merely to be more keenly aware than others of the harmony of the world, of the beauty and ugliness of the human contribution to it, and to communicate this acutely to his fellow-men. And in misfortune, and even at the depths of existence – in destitution, in prison, in sickness – his sense of stable harmony never deserts him.

The artist is simply one who perceives the order embedded in and constituting reality and makes it visible in some striking, new, analogous way. The artist is a receptive medium for truth to speak again to us, in the world and of the world, in all its depth, form, and wisdom.

Solzhenitsyn cannot quite accept this classical vision of the artist. No, he writes, “the irrationality of art, its dazzling turns, its unpredictable discoveries, its shattering influence on human beings – they are too full of magic to be exhausted by this artist’s vision of the world.”

This qualification is right: The end of the virtue of art is the new work, which resists our theories. Theories stand outside art and meddle with its internal deliberations, necessities, and laws that are already hidden within and waiting to be realized. But even after making such allowances, the classical picture of the artist seems the nearest likeness.

Aristotle’s Poetics tells us that poetry is philosophical and deals in probabilities. We approve a story that unfolds in a likely way, and we dismiss those that do not, and that is just to say that we know already that stories have a law to themselves that neither we nor the artist get to decide.

Evelyn Waugh once wrote of his characters, “I really have very little control over them. I start them off with certain preconceived notions of what they will do and say. . .but I constantly find them moving another way.” Telling, writing, and reading stories is a way of discovering the laws that govern not just the craft of story but the actions those stories recount. The nature of reality governs the law of art, and the artist’s work helps us to discern the laws of reality.

I myself started out as a novelist and took delight in seeing how such probabilities gave form – as if with a will of their own – to what I had begun. I turned to writing poetry only when I discovered that the laws of art went deeper into the bedrock of being even than plot and story. A line of verse is governed by number, by the mathematical and logical laws that shape the real near, if not quite at, its very fundament.

In T.S. Eliot’s play, Murder in the Cathedral, Eliot (poet) and Saint Thomas Becket (priest) are one, not because poets are as holy and blessed as are priests. Rather, they are one in their humility. The priest and poet are united in martyrdom, in their bearing witness to an order that transcends us, forms us – on the knowledge of which we rely for our wisdom and salvation.

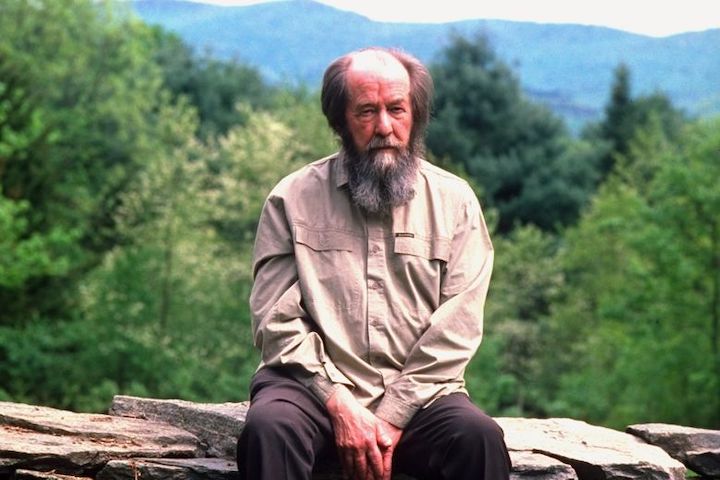

*Image: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Cavendish, VT by Steve Liss, 1989 [The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Archive]