In 2013, Ross Douthat published Bad Religion, a book that argued American Christianity lost its way in the last six decades. Through the seductions of the prosperity gospel and the therapeutic mentality that places self-esteem at the center of all ethical questions, Christianity had betrayed its ancient and authentic truths. These are real heresies, as Douthat calls them, to be sure. But, my first reflex was to ask, “You think religion just got bad then?”

The English philosophical historian and Catholic convert Christopher Dawson launched a series of short books called Essays in Order in 1931. He began by noting that Western civilization was already on its last legs. Indeed, had already collapsed. His series was premised on the belief that it was time for us to begin thinking about rebuilding civilization from its foundations.

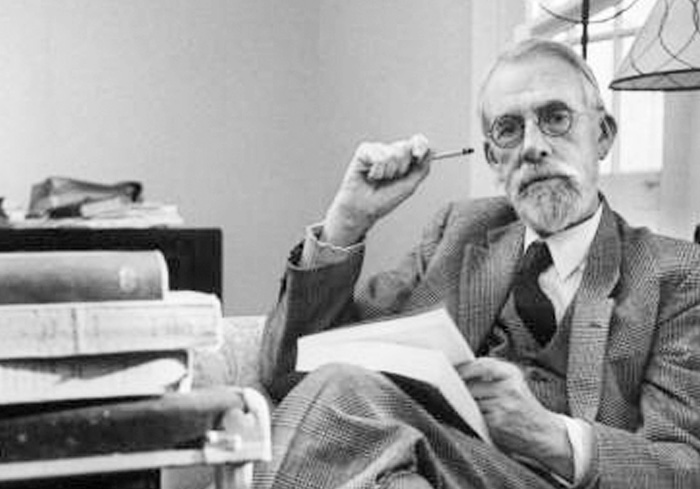

In introducing the series, he not only acknowledges the decline of the West, but also points out that an international Catholic revival has begun – is, in fact, already several decades old. Its leading minds were publishing essays about the reestablishment of order. Among those he published were Jacques Maritain, Carl Schmitt, and Theodore Haecker.

It’s very interesting how Dawson describes the collapse and why he believed Catholics could plant seeds of a new social order. As a convert, Dawson understood from experience the decline into “bad religion.” The Protestantism he knew had, over generations, surrendered its dogmatic, theological, and metaphysical substance in favor of mere morality.

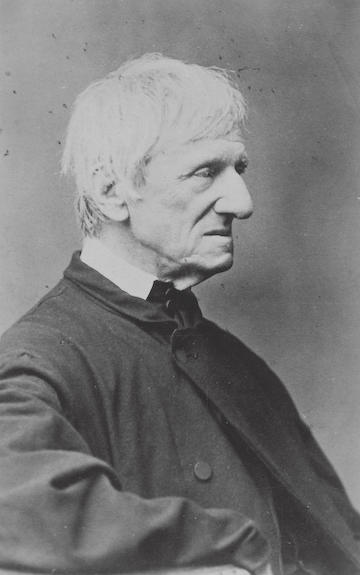

He was correct. Saint John Henry Newman spoke, in old age, of his whole life as a combat against liberalism in religion. By this, he meant an understanding of religion as private truth, or opinion, rather than public dogma. Newman and Dawson both saw with clarity that many modern Protestants had come to think of religion as private because they had first reduced it to mere “moral sentiment.” Religious faith was now considered to be rooted in sentiments rather than in the intellect. It was fit only to pronounce on questions of goodness or morality, not truth or reality.

Newman insists, adamantly so, on what he calls the “dogmatic principle.” Religion is fundamentally a revelation of dogmatic truths to which we must assent, or it is nothing at all. And yet the vocabulary of much of Newman’s writing shows that his own natural idiom was to speak of religion in terms of feelings and sentiments, as if it were chiefly a department of the moral life. He saw well enough the nets, but he could not always escape them.

By 1931, Dawson benefited from Newman’s experiences, as well as the work of those many others who, as he claims, already constituted a mature Catholic intellectual revival. Not least among these was Jacques Maritain and his wide-ranging expositions of Saint Thomas Aquinas, which did much to shape the minds of two generations.

In Dawson’s view, the Christ that liberal Protestants proposed came to instruct us to “love our neighbor” and not to initiate us into such arcane mysteries as the inner life of the Trinity or analogy of created being to God as uncreated Being. The injunction to be good was all that was left.

In Dawson’s view, religion could not survive as mere morality; our view of what kinds of actions are good for us can only be known if we have first determined to what purpose or end we – as a specific kind of being – are ordered. In the 1930s, Maritain argued:

We must know then what man is: which is the office of metaphysics and even of theology. Ethics, which we may consider as the rationalization of the use of Freedom, presupposes metaphysics as its necessary prerequisite. Ethics cannot be constituted unless its author is first able to answer the questions: What is man? Why is he made? What is the end of human life? – (Freedom in the Modern World)

What counts as a moral action for me follows from the kind of being I am – in Aquinas’s language, the kind of form I have. And form, in turn, follows from function, from purpose or proper end.

Maritain did not hesitate to answer these metaphysical questions: “Man is a metaphysical being, an animal that nourishes its life on transcendentals.” We are by nature born for the contemplation of truth, goodness, and beauty, and by way of these three “transcendentals” we are summoned to our fulfillment in the contemplation of God.

In another book, Essay on Christian Philosophy, Maritain explains the ethical implications of this metaphysics. Christianity proposes that man finds his true end only in the contemplative enjoyment, the everlasting friendship, of God. Every last bit of our morality depends upon this conclusion about our purpose and destiny.

If Christians lose sight of the metaphysics, the morality may well stay in place for a while. But, then again, it might not. Our vision of what we are for may shift or alter, entirely unnoticed. Slipping off that transcendent height where, like Moses, we may hope to converse with God, it might gradually slide down ever further until it reaches the level of merely the present hour and declares the feelings and sentiments of this world all that we may know of heaven.

These are precisely Douthat’s examples of bad religion. Long before the 1950s, much of Christendom had lost sight of our proper end and concerned itself only with maintaining “good behavior.” Untethered from dogma, goodness itself was set adrift. “Love thy neighbor” literally does not mean, for many Christians now, what it did for their ancestors.

By treating as superfluous dogma what was, in reality, the essential truth of Christianity, Christianity lost first the purpose of its moral dimension and then it fundamentally altered the content of its morality. Alas, there are times when the Catholic religion seems less the source of a renewal of the moral order, as Dawson expected, and more a belated guest at the liberal Christian feast of mere sentiments.