The priest came in. . .and took out the altar stone and put it in his bag; then he burned the wads of wool with the holy oil on them and threw the ash outside; he emptied the holy water stoup and blew out the lamp in the sanctuary and left the tabernacle open and empty, as though from now on it was always to be Good Friday.

Last Tuesday – the first day of no public Masses in our diocese – I was reminded of this scene from Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited, when the priest came to close up the Marchmain family’s chapel. That last line in particular rang in my mind: as though from now on it was always to be Good Friday.

Granted, the analogy is not perfect. Our situation is not exactly like Good Friday. The Mass is still being offered (albeit privately), our Eucharistic Lord is still present, and our churches are still open for people to come and pray. Still, although necessary, the suspension of public Mass does create a sorrow not unlike Good Friday’s. It is like being exiled from a loved one: you know where He is, but you cannot be with Him.

Here is another painful exile: that of the priest from his people. The faithful throughout the world suffer the pain of life without the Mass. Priests suffer the pain of life without their people. Those men have given their lives for Christ’s flock. Now they struggle to understand their lives apart from that flock. Tend the flock of God in your midst, Saint Peter exhorts the Church’s pastors. (1Pt 5:2) But what to do when the flock is no longer in your midst. . .and not allowed to be?

The whole situation sets in stark relief this truth about us parish priests: we are ordained propter homines – to serve the people of God. Our lives don’t make sense without a people to serve or a flock to tend. When asked what he thought about the laity, Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman famously observed that “the Church would look foolish without them.” As it turns out, it is we priests who look most foolish in that scenario.

We are painfully aware of what happens when a priest loses the supernatural outlook and sense of the sacred. He becomes not just useless but dangerous. A priest must be oriented toward and attentive to the divine first of all. But now we see the other part of the equation more clearly. The priest maintains an orientation toward and focus on the divine not for himself but for others. For every high priest chosen from among men is appointed to act on behalf of men in relation to God, to offer gifts and sacrifices for sins. (Heb 5:1) Without the presence of those for whom he acts, a priest can lose sight of his purpose.

The suspension of public Mass, like any cross we endure, can and should become an occasion for spiritual growth. We need to draw what good we can from this suffering. What might this mean for a priest?

Well, for starters, the absence of a congregation can remind priests that at Mass we stand before the Lord on behalf of our people. Of course, they are not there. But we are there in their place and on their behalf. This highlights the difference between a prayer-leader and a priest. The former simply coordinates and guides a communal action. All he needs is delegation, not divine sanction.

But a priest is appointed to act on behalf of men in relation to God. He stands before the Almighty as the embodiment of the prayers and sacrifices of his people – whether they are there or not. Their absence should increase our appreciation of this truth.

Another bright light is the evangelical generosity and ingenuity of so many flockless priests. During the bombing of England in World War II, Monsignor Ronald Knox retired to Mells to work on scripture translations. He suddenly found himself chaplain to a girls’ school that had been evacuated from London to that sleepy town. Not the best scenario for the bookish Knox. Not what he would have looked for. But his response was generous, innovative, and lasting. From that ad hoc chaplaincy come two of his best works: The Creed in Slow Motion and The Mass in Slow Motion.

So also, many priests apart from their congregations are making the most of things. The situation is sad, and not what they would have chosen. But they are not giving up. They are finding how to evangelize in other, unexpected ways. The Internet makes possible creative solutions, and many have found opportunities there to reach the flock no longer in their midst.

Further, this whole situation reveals the true nature of priestly ministry – that it is really a matter of spiritual fatherhood, of a father being present to his people. The inability to be present in that way painfully highlights the need to be.

This also reveals that all our technology, which we tend to see as the evangelical solution, is insufficient, just a stopgap. It is a fascinating paradox that in this situation we both depend more on our technology and more deeply know its limits. As useful as it is (email, live-streaming, posted videos, etc.), it cannot actually put us in touch with one another. It only tides us over until authentic human communication – unmediated, face-to-face, person-to-person – can be recovered.

There is no substitute for the shepherd’s presence among his people. And a priest’s heart cannot be content with a virtual connection. It longs for the real.

One last rose drawn from these thorns: an increased appreciation for our people’s devotion. The lack of a public Mass on Sunday will greatly impact the lives of all Catholics, whether they realize it or not. But many do realize it. They long for the Mass, they still come to the church to pray, and they desire to receive all that a priest desires to give. To see their pain and longing should encourage us to be worthy of them.

Ours is an unexpected advent in the midst of Lent. We are waiting – and thus preparing – for when the priest of Christ can again be with his people.

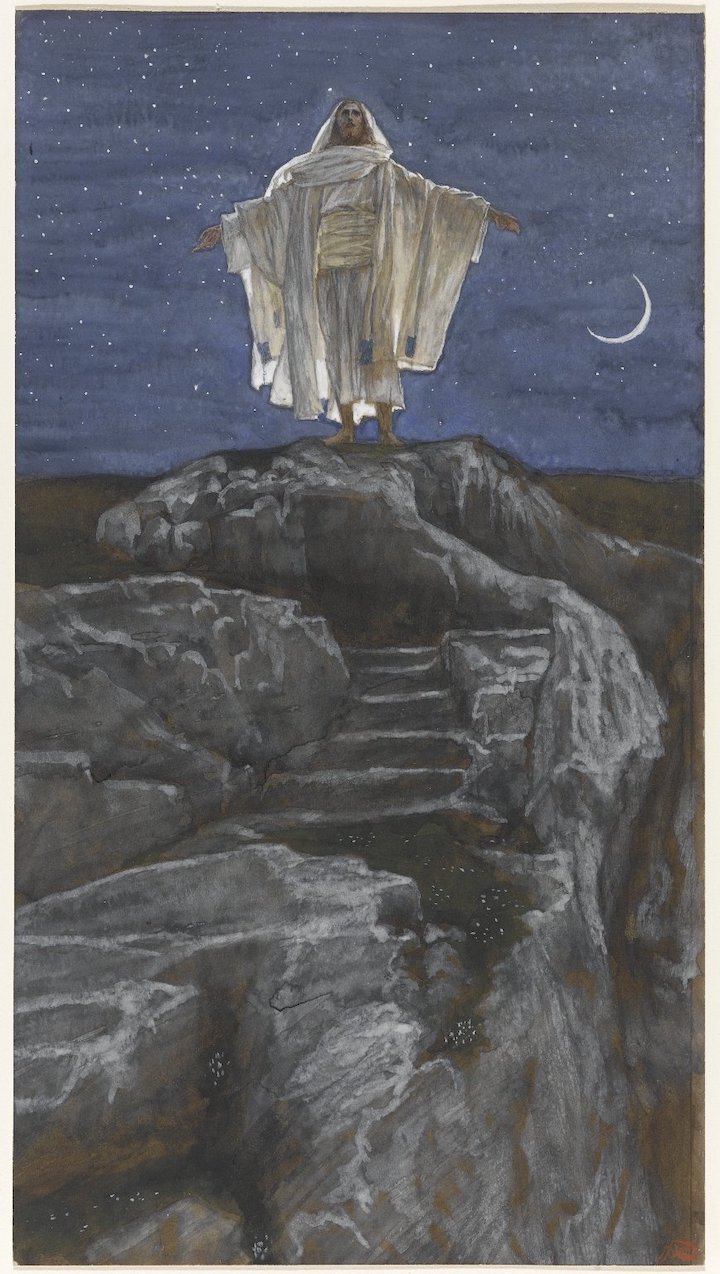

*Image: Jesus Goes Up Alone onto a Mountain to Pray by J.J. Tissot, c. 1890 [Brooklyn Museum]